The Myth of the ‘Underage Woman’

One more shameful truth Jeffrey Epstein symbolized: a culture that continues to write girls out of its stories

On Monday, the New York Times columnist James B. Stewart published a remarkable article: a summary of an interview he had conducted last August with Jeffrey Epstein. The two were ostensibly talking together about matters of business—about rumors that Epstein had been doing advisory work for the electric-car company Tesla. But Epstein, in Stewart’s telling, kept guiding the conversation toward the secret that was at that point no secret at all: the fact that Epstein was a convicted sex offender. “If he was reticent about Tesla,” Stewart wrote, “he was more at ease discussing his interest in young women”:

He said that criminalizing sex with teenage girls was a cultural aberration and that at times in history it was perfectly acceptable. He pointed out that homosexuality had long been considered a crime and was still punishable by death in some parts of the world.

It’s an argument that is reminiscent of the glib comments Epstein made following his release from a 13-month semi-incarceration, the result of a shockingly lenient plea deal struck in 2008. (“I’m not a sexual predator; I’m an ‘offender,’” Epstein told the New York Post in 2011. “It’s the difference between a murderer and a person who steals a bagel.”) The 2018 version of the argument added a new element, though: It suggested that consent laws were little more than prudishly narrow accidents of history. It insisted that Epstein himself was that most tragic, and heroic, of figures: a person born in the wrong place, at the wrong time. And it attempted, in all that, a sweeping feat of erasure: Epstein’s claim attempted to undermine the testimonies of the more than 80 women who have come forward to say that Epstein molested them when they were girls. Some of the women say they were as young as 13 when the predations began.

“He wanted as many girls as I could get him. It was never enough,” Courtney Wild, one of Epstein’s alleged victims, told the Miami Herald reporter Julie K. Brown.

“The women who went to Jeffrey Epstein’s mansion as girls tend to divide their lives into two parts: life before Jeffrey and life after Jeffrey,” Brown noted.

“He ruined my life and a lot of girls’ lives,” said Michelle Licata, another of Epstein’s alleged victims.

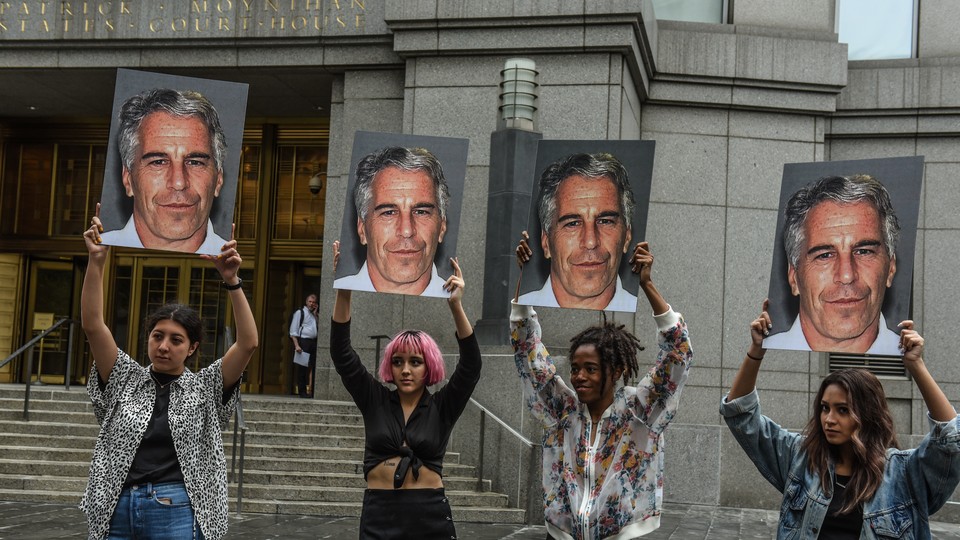

Girls. Girls. Girls. This is the crux of it. “He told me he wanted them as young as I could find them,” Wild said. When the Epstein story re-broke as news in early July, however—because of an indictment brought by the Southern District of New York, and aided greatly by Brown’s reporting—a common error began to spread: Many media outlets referred to Epstein’s victims, both acknowledged and newly alleged, as “underage women.” The New York Times used the term. So did New York magazine. Jezebel counted 90 instances of it aired on broadcast news in the days after Epstein’s arrest alone.

The phrase is wrong in every sense: There is no such thing as an “underage woman.” Underage women are girls. But the mistake, repeated several times since July, has been in its own way revealing. It suggests an American culture that remains reluctant to equate the interests of powerful men and the interests of vulnerable girls. And it suggests an ongoing ambivalence about what it means to be a girl in the first place.

The underage woman exerts its errors within the same commercial culture that found Elizabeth Hurley, in 2012, selling a bikini set, tiny and leopard-printed, aimed at “girls [ages 8–13] who want to look grown up.” It operates in an environment where school dress codes routinely punish girls for wearing outfits that are deemed distracting to male students. It operates in the setting the journalist Peggy Orenstein documented in her 2016 book, Girls & Sex—a work that details how many girls of the moment are taught, despite feminism’s alleged advances, to view themselves as sexual objects. The underage woman, with its insistent contradictions, operates in a culture in which a song from the 1950s retains its cringey purchase: Thank heaven for little girls / For little girls get bigger every day / Thank heaven for little girls / They grow up in the most delightful way / Those little eyes / So helpless and appealing / When they were flashing / Send you crashing / Through the ceiling …

The song, from the soundtrack to the film Gigi, is apt: Hollywood has a long history of insisting that girls in general, and teenage girls in particular, are simply women in a kind of disguise. And it has a long history, as well, of endorsing the idea that Gay Talese observed in 1981, in his book Thy Neighbor’s Wife: “The penis … knows no moral code.” The two notions have sometimes collided. American Beauty, starring Kevin Spacey as a middle-aged man who develops a crush on his teenage daughter’s best friend, is soon to hit its 20th anniversary. Election, whose plot turns on a sexual relationship between a middle-aged teacher and his teenage student (Reese Witherspoon), hit the 20-year milestone earlier this year. And then there’s Manhattan, which finds Woody Allen playing, as always, a version of himself—in this case, a 42-year-old writer—dating a 17-year-old high-school student (Mariel Hemingway). There was also, until its release was canceled in late 2017, the Louis C.K. film I Love You, Daddy—which stars Chloë Grace Moretz as a 17-year-old who engages in a relationship with a famed director 50 years her senior. (C.K. plays her father.)

And there is, of course, Lolita—a complicated consideration of child sexual abuse that has been generally metabolized, over the decades, as a simple justification of it. “I was a daisy-fresh girl and look what you’ve done to me,” the girl whose given name is Dolores seethes, plaintively, in Vladimir Nabokov’s book; Lolita, however, as a transcendent kind of trope, is not angry at her abuser. She is not capable, indeed, of much emotion at all. Lolita the archetype, instead, functions as a foil to the (straight) men who encounter her. She is tempting, seductive, justifying. She is thoroughly male-gazed. Girl, you’ll be a woman soon. Soon, you’ll need a man.

There is a teasing quality to many of these pop-cultural treatments of the underage woman, just as there was a teasing quality to Epstein’s claims about the historical contingencies of sexual taboos: They take refuge in a dark kind of satire. The Hollywood-sanctioned explorations of sexual relationships between middle-aged men and teenage girls are not endorsing those relationships, they insist. They are merely asking what things would be like if laws hadn’t been written as they were, if norms hadn’t settled into their current and contingent shapes. The works tend to treat the girls as simultaneously available and inaccessible—and primarily as vehicles of self-discovery for the men who are the films’ true stars. The stories they tell belong to the guys who are sad and frustrated and misunderstood; the girls serve as mere accessories to those stories. They call to mind what the journalist Vicky Ward, who has been reporting on Epstein for years, recently told the Times: Most everyone in Epstein’s orbit mentioned “the girls,” she said, but “as an aside.”

The logic of Lolita hovers as a specter over Epstein’s story. His private jet was widely known as the “Lolita Express.” He flaunted the girls as if they were furniture—making a display, reports suggest, of their youth and their vulnerability. But the girls’ childishness asserted itself, as well. Alfredo Rodriguez, who worked as Epstein’s butler in the mid-2000s, told a Palm Beach detective investigating the Epstein case that he had suspected the girls in Epstein’s orbit were underage in part because, as the detective summed it up, “they would eat tons of cereal and drink milk all the time.” The lead illustration for Brown’s extensive 2018 report on Epstein in the Miami Herald—the one that helped lead to the new indictment that was brought against him this summer—features an image of Epstein, rendered in color, surrounded by black-and-white headshots of four of the girls who have accused him of abuse. Some of them, in the photos, are wearing braces.

These are the people whose lives and whose dignity Epstein was mocking when he compared his crimes to the stealing of a bagel. This is what his version of that dully familiar standby, the open secret, looked like. Epstein took refuge in a culture that revolves, still, around the whims of the wealthy and the straight and the male. He found protection within the networked strain of impunity that for so long kept the secrets of, among so many others, Bill Cosby and R. Kelly and Harvey Weinstein. Epstein lived in a culture, he knew all too well, that is not yet accustomed to putting girls at the center of the story. The rest of the Gigi song goes like this: Thank heaven for little girls / Thank heaven for them all / No matter where / No matter who / Without them / What would little boys do …

More than 50 years later, many things have changed. Many things have not. Roy Moore, accused of sexually pursuing teenage girls when he was in his 30s, lost his bid for a seat in the U.S. Senate in 2017. Two years later, though, Moore, apparently encouraged by current conditions, announced that he would seek the seat again. This summer, Jeffrey Epstein was indicted; this summer, as well, Jeffrey Epstein, under circumstances that are still unclear, evaded justice once and for all by apparently taking his own life. “I am angry Jeffrey Epstein won’t have to face his survivors of his abuse in court,” Jennifer Araoz, who has accused Epstein of raping her when she was 15, said on Saturday, reacting to the news of his death. “We have to live with the scars of his actions for the rest of our lives, while he will never face the consequences of the crimes he committed, the pain and trauma he caused so many people.”

Yesterday morning, however, Araoz filed a suit against Epstein’s estate—as well as against Ghislaine Maxwell, his alleged accomplice, and three unnamed women on Epstein’s household staff. Araoz filed the suit under the auspices of a new law in New York State, NBC News reported, that allows civil cases to be brought against those who have allegedly engaged in the sexual abuse of minors, regardless of how long ago the claimed abuse took place. The law, which provides a one-year window for the suits to be brought, went into effect yesterday. It is called, appropriately, the Child Victims Act.