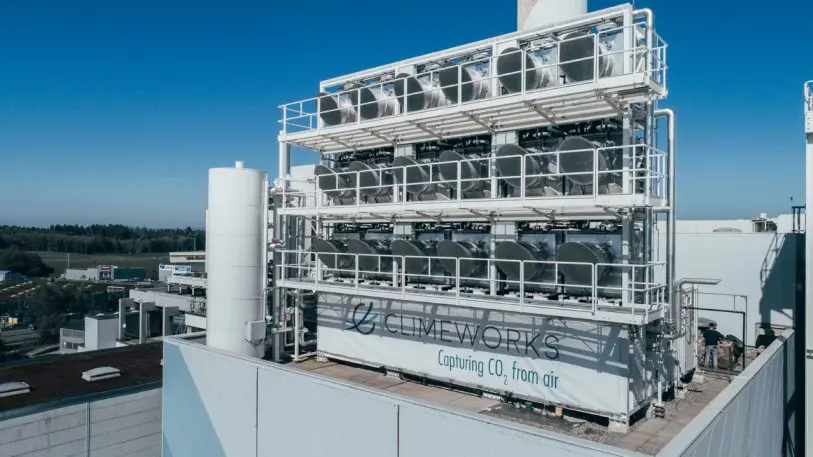

Sitting on top of a waste incineration facility near Zurich, a new carbon capture plant is now sucking CO2 out of the air to sell to its first customer. The plant, which opened on May 31, is the first commercial enterprise of its kind. By midcentury, the startup behind it–Climeworks–believes we will need hundreds of thousands more.

To have a chance of keeping the global temperature from rising more than two degrees Celsius, the limit set by the Paris agreement, it’s likely that shifting to a low-carbon economy won’t be enough.

At the new Swiss plant, three stacked shipping containers each hold six of Climeworks’ CO2 collectors. Small fans pull air into the collectors, where a sponge-like filter soaks up carbon dioxide. It takes two or three hours to fully saturate a filter, and then the process reverses: The box closes, and the collector is heated to 212 degrees Fahrenheit, which releases the CO2 in a pure form that can be sold, made into other products, or buried underground.

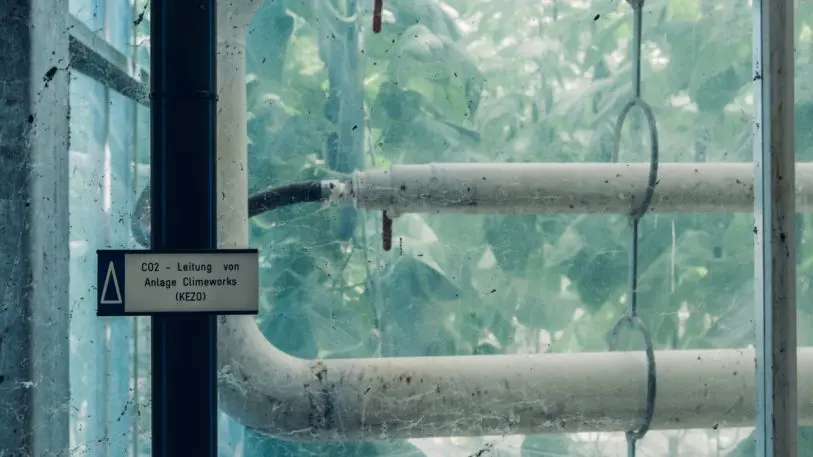

In the case of the first plant, the customer is a neighboring greenhouse, which uses the CO2 to make its tomatoes and cucumbers grow faster (plants build tissue by pulling carbon from the air, and more carbon dioxide means more growth, at least to a degree). Climeworks is also in talks with beverage companies that use CO2 in sparkling water or soda–particularly in production plants that are in remote areas, where trucking in a conventional source of CO2 would be expensive.

“There, Climeworks’ plan–taking it out of the air directly on site, is very advantageous and also commercially attractive already as of today,” says Wurzbacher. “We still have to go down a couple of steps on the cost curve, but in these niche applications already today, we can offer competitive CO2.”

Ultimately, the company wants to sell its ability to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it underground, and it thinks that the market may be ready to pay sooner than the startup initially expected. The IPCC, the international body that issues massive, comprehensive reports on climate change, has estimated that the world will need to be removing an average of 10 gigatons of CO2–10 billion tons–a year from the atmosphere by midcentury.

“If we say that by the middle of the century we want to do 10 billion tons per year, that’s probably something where we need to start today,” says Wurzbacher. “Based on our experiences now on the market, we are very confident that we will be able to develop a market in the very near future, maybe next year or in two or three years, to sell these negative emissions.”

Because there isn’t yet a global price on carbon, the company imagines that the first customers might be corporations that need help reaching ambitious climate goals. After adopting more obvious solutions, like renewable energy, increased efficiency, and changes in materials or transportation, a company might turn to negative emissions to help it offset the remainder of its footprint.

Planting trees or preserving existing forests is likely to also be a critical way to absorb CO2. “The best example of carbon dioxide removal technology that we know how to do now is grow more forest and to protect the carbon content of soils,” says Field. “And those are technologies that we know how to do now that provide extensive co-benefits and are ripe for taking advantage of.”

But direct air capture plants have some advantages that could make them an important part of the solution as well: The CO2 capture plant is roughly a thousand times more efficient than photosynthesis.

Still, to have the impact needed, the CO2 capture plants would need to be built at a massive scale. The first plant in Switzerland can capture 900 tons of carbon dioxide in a year, roughly the same amount of emissions as 200 cars. The company calculated how many shipping container-sized units would be needed to capture 1% of global emissions; the answer was 750,000.

In one sense, Wurzbacher says that this is less enormous than it might seem. The same number of shipping containers pass through the Port of Shanghai every two weeks. But to capture the 10 gigatons of emissions needed, between 10 and 20 other carbon capture companies would have to have equally large operations. (As of today, a handful of others, such as Carbon Engineering and Global Thermostat, are working on similar technology.)

Field, the Stanford scientist, argues that it’s important to remember that the technologies, while promising, are early-stage and unproven, and will face challenges in scaling up, especially if there isn’t a price on carbon. He also says it’s critical that people don’t get the wrong idea about the potential–the possibility of carbon capture isn’t a license to pollute more now.

But that note of caution doesn’t mean the technology isn’t necessary. “CO2 removal is a really good idea,” he says. “And a lot of the technologies ought to be deployed today. A lot of technologies ought to be explored.”

“Air capture costs money, so anything we can do which is cheaper than air capture, we should do it, definitely,” says Wurzbacher. “But we’ll need this on top of that. And we’ll not only need to develop it today, but we need to start scaling it today if we want to be able to put away these 10 gigatons every year by 2040 or 2050.”

Capturing carbon, he says, is as important as the massive shift to a low-carbon economy. “It’s not either/or,” he says. “It’s both.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.