The New Demographics of Suicide

A new report from the World Health Organization challenges notions of who's at greatest risk.

The World Health Organization (WHO) released a report this week that has piqued the interest of the public health community for its surprising findings on who commits suicide.

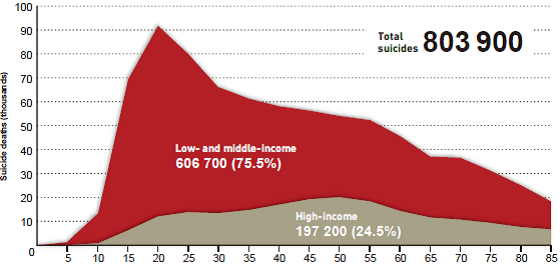

One dramatic trend the WHO reports is that countries in the developing world have suicide rates that are many times higher than the Western world.

“Despite preconceptions that suicide is more prevalent in high-income countries," the report states, "in reality, 75 percent of suicides occur in low- and middle-income countries."

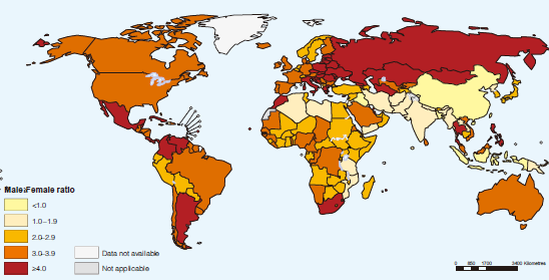

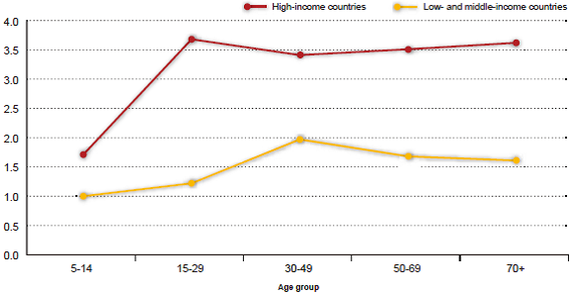

The high male-to-female ratio of suicide victims is also rapidly equalizing, particularly in the developing world. The changing makeup of the global workforce and its increasing inclusion of women have made women more susceptible to the socioeconomic stress that increases the likelihood for suicide. While the male-to-female ratio for high-income countries is 3.5, the ratio is almost even in low-income countries at 1.6. The divide is particularly close in the Western Pacific (0.9), Southeast Asia (1.6), and the Eastern Mediterranean (1.4).

Variation in suicide rates by age is also important. Younger women in the 15-to-29 age bracket are as likely as their male counterparts to commit suicide in developing countries at a 1:1 ratio. The gap widens up to middle age, but in general, data indicates that the gender of suicide victims can be male or female, unlike the male dominance of suicides in the developed world.

While suicide is statistically more common among those who fall in the 15-to-29 age bracket, people over the age of 70 are in fact the prime demographic for suicides. And as with the gender divide in suicide, it seems that elderly women in particular are becoming more susceptible. As the population pyramid leans towards an older demographic, an entire segment of people who might not otherwise be popularly associated with suicidal tendencies—and are often ignored—face a growing, disturbing epidemic.

Ultimately, the report deconstructs some preconceived notions that people might have about suicide, but Dr. Margaret Chan, director-general of the WHO, reminds us that the problem is universal in its “devastating and far-reaching” effects on families and societies. Thinking about tragedy on this scale, about death tolls in the thousands, can be numbing. Of course, as Chan writes in the prologue, “Every single life lost to suicide is one too many.”