Genetics

The Meaning and Meaninglessness of Genealogy

Researching our family background is all the rage, but what does it all mean?

Posted January 29, 2018 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

The practice of genealogy, researching one’s ancestors, has exploded lately. Ancestry.com has become a huge success, boasting millions of subscribers and a net worth well into the billions. Many, if not most, families in the US have at least one person actively researching the long-forgotten twists and turns of their family tree.

It’s an understandable obsession, of course. The preoccupation with who we are and where we came from has plagued humanity since the dawn of civilization. We put up pictures of our great-great-grandparents, whom we never met and are long dead, and bore all of our houseguests with their stories. But what does it all really mean?

Genealogical Surprises

Ancestry.com and other genealogy businesses have made a common practice of digging deep into the background of celebrities (something people are obsessed with even more than genealogy) as a means to attract publicity and new subscribers. In 2008, it was revealed that then-presidential candidate Barack Obama was related to Vice President Dick Cheney. This is an example of the fascinating things that genealogy can reveal about our backgrounds.

What does it say that Barack Obama and Dick Cheney are distant relatives, sharing an ancestor that lived in Maryland more than 400 years ago? If you ask me, I say it means almost nothing.

Until he entered politics, the life of Barack Obama could not have been more different than that of Dick Cheney. Obama grew up as the son of a single mother, partly in progressive and multicultural Hawaii and partly in the island nation of Indonesia. His father was largely absent and his grandparents raised him as much as his mother did, particularly when he remained in Hawaii as his mother returned to Indonesia. Cheney, on the other hand, had the stereotypical all-American childhood in Nebraska. It is hard to imagine two citizens of the United States with more different backgrounds. Because of a long-ago shared ancestor, do they really share a cultural background?

The ancestor that links Cheney and Obama is Mareen Duvall, a French Hugenot that arrived in the British colony of Maryland in 1650. He built a very successful plantation and sired many children by three successive wives. Mostly through luck and his high station, detailed records of his immigration, estate, and family life happened to have survived. His famous descendants include President Harry Truman, Wallis Simpson, Warren Buffet, Robert Duvall, and many others besides Cheney and Obama.

These celebrities share their Duvall ancestry with tens of thousands of US citizens and there is even a society formed to track the many progenies of Duvall. It just so happens that Mareen Duvall and his immediate descendants left many children, ensuring a sprawling family tree. This, too, is largely due to luck of the draw. While, historically, wealth and status did increase the likelihood of leaving a large genetic legacy, it was no guarantee. The list of the rich and powerful that have no living descendants includes William Shakespeare, George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, James Madison, Henry VIII, Louis XVI, and Mark Twain.

The larger point that is raised by the relatedness of Obama and Cheney is that any two randomly selected individuals sharing some racial background and living in the same country will have a high likelihood of sharing an ancestor if you go back far enough. Indeed, Ancestry.com has since revealed that Barack Obama is also related to George Washington, Lyndon Johnson, Gerald Ford, James Madison, George W. Bush, Sarah Palin, and Rush Limbaugh. There have been many chuckles at the fact that Barack Obama is related to Brad Pitt, while Hillary Clinton is related to Angelina Jolie. Clinton is also related to Madonna, Celine Dion, and Alanis Morissette. Perhaps there is a penchant for becoming a pop star in the genes of that family? As the lists of famous people related to other famous people grow, the fascination wanes and the underlying truth starts to materialize: we are all related.

The fact is, if you go back far enough, each one of us has a shared ancestor with every other person on earth. Scientists estimate that the most recent common ancestor of all humans lived just a few thousand years ago. Let that sink in for a minute. There was someone, a specific man or woman, who probably lived in either Egypt or Babylonia during the classical period, to whom we can all trace our ancestry.

Assuming an average generation time of 20 years, this means that we are all 120th cousins, descended from someone that was alive when the pyramids were already aging structures. (Many millions of other people living at that time also have living descendants, of course. The last common ancestor is simply the one who is an ancestor to all of us, in addition to our many other ancestors who are not common to everyone.)

Of course, within a given ethnic group, the most recent common ancestor will be much more recent than that, especially so within a limited geographical area with low ethnic diversity. Remember that, randomly, some people leave many descendants and others leave none. If you take a country like Scotland, Sweden, or Poland, you really don’t have to go back very far before you discover someone that is a shared common ancestor to the vast majority of living citizens. For example, in the lands of the former Mongolian empire, around 8% of the population are direct descendants of Genghis Kahn and that goes less than 800 years back. Even as far away as North America, around 0.5% of men carry the Y-chromosome of the great Kahn.

Many millions of Americans of Irish ancestry trace their families back to a specific county in Ireland, but the reality is that, if you’re Irish, you are related to all other Irish people and probably a lot more closely than you think.

In fact, everyone on earth with any trace of European ancestry probably has a shared ancestor who lived in the early Middle Ages. Charlemagne has been proposed as a possible candidate.

Family trees aren’t correct anyway

One thing that Ancestry.com won’t often tell you is that the genealogy that you discover may not be accurate anyway. Inferences have to be made when you are dealing with records that are hundreds of years old. There are many surnames and first names that are quite common. There is no way to be sure that the “Jacob Carter” that turns up in one record is the same “Jacob Carter” that shows up in another from 15 years later, even in the same general area.

Then, as now, many families were on the move. An isolated census record containing only a name is nothing more than a low-resolution snapshot. There is no way to know how many links and associations that genealogy reveals are simply coincidence.

Furthermore, over the past two centuries, it was not uncommon for last names to be changed, misspelled, or misattributed. Records were frequently lost, recreated, or even forged. We think of our identities as relatively fixed now because we have traceable identification cards, birth certificates, and social security numbers from a very early age. But none of that existed until recently.

Many families had secrets covered up with lies. Troubles with the law or social scandal often led families to relocate, change names, and invent a past. Forging records was much easier in the past, especially when moving to a different region or country.

For example, secret adoptions have been commonplace in the western world since the middle ages. A pregnancy in an unmarried young woman was often “handled” by attributing the baby to a different family member or even through adoption to an unrelated family. This was almost always concealed from official registries and kept as a tightly guarded secret taken to the graves.

On top of this, misattributed paternity was a lot more common in the past than it is now. As I’ve written previously, blood type testing revealed that around 5% of the children born in England in the 1940s could not have been the biological offspring of their fathers. Other studies have put this number even higher. Considering that misattributed paternity has, on average, only a 50% chance of leading to a suspicious blood type, the actual rate was probably double the 5% reported in the paper.

Before the advent of DNA testing, there was no way to detect misattributed paternity and it was present at much higher rates than we like to admit in polite company. (While misattributed paternity in the developed West is likely now below 2%, it is as high as 20% in some underdeveloped regions of the world.)

If your family tree goes back a few generations, it is almost certain to contain an error or two. In fact, there could be entire branches that are based on a lie and you would have no way of ever knowing.

Many people react to the specter of misattributed paternity or concealed adoptions with an incredulous declaration that “it doesn’t matter,” and that the important feature of genealogy is the family history and the connection with our past, not the precise genetic relationships. I quite agree. So why are family trees needed to appreciate our forebears and we do we obsess about the genetic relationships when we know that they don't matter? Learning about the struggles and joys of generations past can resonate with all of us regardless of who is descended from whom.

Our experience is about culture, not genes

Another problem with putting so much stock in our genealogy is that this over-emphasizes genetic relationships over social and cultural history (or at least attempts to). We draw our identity from our experiences and we are deeply imprinted by the cultural themes of our society and the parents that raised us, regardless of where we got our chromosomes.

If you found out that your great-grandfather was not actually a poor Belgian immigrant who died of influenza before his daughter was born, but a French aristocrat who seduced or even raped your great-grandmother, how would that change your self-identity? I sure hope it wouldn’t change it at all. The culture in which we are raised shapes us as much as our parents do. The cultural influence of our ancestors fades with each generation anyway. The cultural imprints that were left on your great-great-grandparents have long since given way to the more recent cultural milieu.

In my own family tree, almost all of my ancestors can be traced back to modern-day Germany. Yet, neither I, nor any of my cousins speak German or remember any family members that did. We don’t eat German foods or keep any German traditions. There were even several spelling changes in our family history around the time of the world wars that served to distance the family from our German roots. When I visited Germany in 2000, I felt precisely zero cultural connection. I didn’t like the food; I didn’t appreciate the traditions, and I didn’t particularly bond with the people. I am as German as sushi.

The notion of “genetic stock” is spurious anyway. What sense does it make that I am called German because some ancestors, five or more generations back, emigrated from a region of the world that is now called Germany? Germany wasn’t a single unified country at that time, nor was there a sole German culture. We don’t even know the towns that my various forebears hailed from, but it wouldn’t matter if we did.

Most Italian Americans are the descendants of immigrants that came to the US long before Italy was a unified country. Sicily and the Italian peninsula were divided into many regions, some autonomous, some parts of larger Kingdoms. At that time, Neopolitans wouldn’t have thought of themselves as part of the same culture as Venetians at all. They had different foods, customs, traditions, and even spoke different dialects of the Italian language. When they arrived in America, they endeavored to establish a common "Italian" culture in order to find solidarity in a country with deep ethnic and nationalist divisions. This common Italian American culture is quite distinct from the parent Italian cultures.

When I was in Ireland, I was amused at how often I would hear Irish nationals correct American tourists claiming to be Irish. “You mean Irish American,” they would delight in saying. Most of us think there is nothing more Irish than corned beef and cabbage on St. Patrick’s Day, but that is not a tradition in Ireland.

Another example of the dubious nature of genetics as a conveyor of cultural identity is found in the Jewish diaspora. The small bands of Jews that left the Levant mostly after 1000 A.D., made settlements throughout Africa, Europe, and Asia. During nearly all of that time, Jewish law and custom strictly forbade intermarriage. A Jew that married a non-Jew would be Cherem (shunned) and forced to leave the community.

Nevertheless, genetic testing has revealed that Jews throughout the world have, to varying degrees, the distinct genetic fingerprints of their non-Jewish neighbors. To be sure, the genetic traces of their Levantine ancestors are prominent throughout world Jewry, but their DNA is now a mixture of their new homeland and their ancestral one. This demonstrates the power of even the rare instance of tolerated intermarriage or misattributed paternity to alter the genetics of a people over time.

On the other hand, this also shows that genetics is a poor proxy for marking the character of a culture. From medieval times through the Shoa (holocaust), few cultural identities were as distinct and cohesive as Jewry. That the genetics sometimes tells a different story doesn’t undermine that identity; it shows that genetics is meaningless, or nearly so, for establishing who can lay claim to a culture. Family ties are about shared culture, not genes.

Genealogy is often presented as a celebration of modern cultural diversity, particularly in the United States. If that were so, why does genealogy value genetics over cultural connections? Culture does or should encompass all individuals, regardless of their race or ancestry, but the implicit assumption in genealogy is that only those of the precise genetic stock are entitled to claim the patrimony. That would seem to promote racial and ethnic divisions, rather than diversity.

So what is the point?

Given these truths: all humans are related; those of a given ethnicity are even more closely related, and social context shapes our identity much more than genetics, I ask, “What is the point of researching our precise ancestry at all?” The answer seems to be that a connection to our recent ancestors is what compels us to study our genealogy. It is their stories that fascinate us, not their genetic stock.

Ancestry begins to lose its luster after eight or ten generations, not least of all because the records almost never go back further than that anyway. Even if they did, the number of ancestors would be overwhelming and we would surely latch on to a few of the more prominent or interesting ones. Likely, we’d share those prominent ancestors with hundreds of thousands or even millions of others, so what claim do we really have to individuality because of that ancestor?

The stories of our recent ancestors drive our fascination with genealogy because they give us something unique to hang our hats on, a story that belongs solely to our particular family. You may be the only one you know that has an ancestor from a specific village in Italy. Or maybe one of your forebears was a member of an aristocratic family that chose love over fortune and eloped with a commoner. Perhaps your great-grandfather survived the sinking of the Titanic or fought against the Ottoman occupation of his homeland. These are the romantic stories that compel us to seek our genealogy and take pride in whatever it reveals.

Some uncomfortable realities about genealogy

The widespread fascination with genealogy has a dark side. To start off with, it’s a hobby that is more easily enjoyed by the dominant group of our racial and ethnic demographics, meaning wealthy white Christians with long roots in this country. Until quite recently, only prominent families left much of a paper trail. The poor masses had their children in their homes unannounced in local papers. This means that Europeans and white North Americans will have an easier time finding at least some records for parts of their family tree.

For many African Americans in the US, what could genealogical research reveal that we don’t already know? Five or six generations ago, an ancestor was abducted, bound, and transported to the US to be sold into slavery. Nothing was or ever will be known about her or him other than possibly the general region from which they were purchased within the larger West African slave market. Then, two or three generations after that, an enslaved ancestor was freed, often with the last name of his former captor. It's hard to romanticize a genealogy filled with tremendous suffering.

The story is similar for Native Americans. While genealogical research can undoubtedly uncover stories of courageous defiance and dedication to tradition, heritage, and, family at great cost, most of those stories were lost long ago. The family trees of all Native Americans are filled with courage, tragedy, and grief. The process of genealogy produces a few heartening stories that exclusively “belong” to some families when really they should belong to all of them.

Many recent descendants of immigrants from Latin America, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East are also frequently left out of the fun of genealogy. Underdeveloped regions usually have no paper trails to be found, which furthers the self-perception that these immigrants are “other” and not part of the cultural stock of their adopted homelands. While that may be partly unavoidable, our recent obsession with genealogy could extend the marginalization of immigrants further into subsequent generations than it would have otherwise.

The last group that may be negatively affected by the increasing popularity of genealogy are adopted persons. Children and adults who are raised by adoptive families already have a higher likelihood of feeling that they don’t quite fit in. Watching friends and neighbors research their family tree could exacerbate this. The adopted may or may not feel a connection to the ancestors of their adoptive parents, and may or may not be able to learn anything about their own biological antecedents. Seeing how others express their identity through their genetic lineage, especially non-adopted members of their families may leave them feeling less connected. It could even drive them toward a search for their biological families that may or may not prove fruitful and that may or may not result in healthy experiences for them. I’m not saying that it is always wrong to enjoy something that not everyone else can enjoy. However, the emphasis on genealogy as a source of identity seems acutely harmful to at least some adopted people.

Biogeographical Ancestry

More molecular forms of ancestor-seeking have now burst onto the scene with millions of people having their DNA analyzed by 23andme, Ancestry.com, National Geographic, and others. There are two big problems with this, however. First, different companies can give quite different results, and secondly, the whole process of assigning DNA sequences to geographic ancestry is probabilistic, not certain, and this isn't always presented clearly. In some cases, the error range can be huge. In other words, the science is just not there yet and it might never be, given how intermixed we all actually are. Individuals and families were always crossing borders and mixing together.

At best, an "ancestry report" can only tell you that some of your ancestors likely lived somewhere within a big and poorly defined region for maybe a few generations.

Taking pride in one’s ancestors

Of course, I understand why people have a strong attachment to their ancestors and seek to learn as much as they can about them. We all search for a connection to our roots, our past, and things we can take pride in. The flip side is that we may find things that we may feel shame for, a relative that committed heinous acts or was otherwise the subject of scandal.

Upon reflection, neither of those reactions really makes sense to me. Are we guilty of the sins of our fathers? Can we take credit for their successes? If your great-great-grandmother was a suffragette and fought alongside Susan B. Anthony, that is her heroism to take pride in, not yours. On the other hand, if we discover that we are a descendent of a famous, heroic, or commendable person, how could we not take pride in that?

I have little doubt that, if I found out that I was related to Nathaniel Hawthorn or Frederick Douglas, I would work it into any conversation I could. In fact, my grandmother believed that she was related to William Jennings Bryan. I used to take pride in telling people that until I saw Inherit the Wind and read about Bryan’s role in the Scopes trial. I rarely boast of that possible relation anymore. I am confused by even my own reaction to genealogy.

Two stories help bring this conundrum into focus for me.

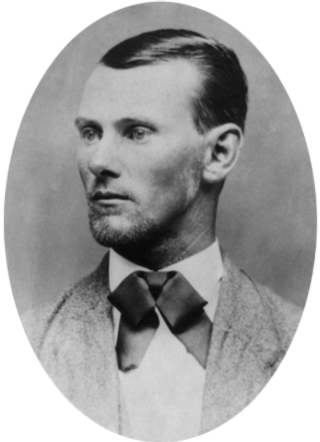

On the inaugural episode of “Genealogy Roadshow,” a woman was seeking help from professional genealogists to confirm or refute the folklore that her family was related to the outlaw Jesse James. Before revealing the answer, the genealogist gave a rundown of the many crimes of Jesse James, most revolving around James’ staunch support for the confederate cause of slavery and secession. James killed many innocent civilians during and after the Civil War through terrorism, lynchings, and large-scale massacres. The prospective relative of this odious man nodded her head in agreement as the horrific crimes were read. When the genealogist revealed that she was indeed related to Jesse James, the woman cheered in excitement and pumped her fist. The genealogist, an African American, merely smiled, apparently not moved to share in the celebration.

Another story is one of my own. I was once in a conversation about family histories with an African American friend of mine. I mentioned that I had several ancestors that fought for the union during the Civil War and some others that were active in the Republican Party in Sangamon County, Illinois. The GOP at that time was the anti-slavery party and Sangamon County was where a young Abraham Lincoln got his start. My friend, on the other hand, is a light-skinned African American, whose two parents are also light-skinned. The legend on both sides of his family is that an ancestor was the favorite if unwilling, female slave of a white slave owner, a phenomenon that was not at all uncommon.

At one point, my friend said to me, “So wait, that means that you are descended from abolitionists and I am descended from slave owners?!”

Is the implication that he should share a part of the shame of slavery, transmitted through his genes, while I should stand self-righteous, having inherited the title of “abolitionist?” Of course not. But what does it say?

Confession: I have attachment to my genealogy

Now is when I have to come clean and admit that I have enjoyed keeping up with the efforts of my relatives to trace our family tree. I have pictures on my bedroom wall of ancestors that I’ve never met, but whose story I tell. It’s natural and alluring to dive into the stories of our past. I do not feel that anyone should feel guilty for enjoying their genealogy.

Further still, shows like Genealogy Roadshow, co-hosted by a prominent genealogist that specializes in African American genealogy, have gone to great lengths to show that the family stories of African Americans, Native Americans, and Latin Americans can be as rich and interesting as that of the white folks that have been the dominant focus of casual genealogy until recently.

I don’t mean this post as a condemnation of the pursuit of genealogy. Our history is very important to us and has shaped us in innumerable, unknowable ways. It is vital that we, as a people, know our history. I just think it is good to keep the limits of genealogy in mind and to keep its value in context.

There were many heroes and villains in ages past that impacted our world in myriad ways. There were also countless ordinary folks, now nameless, that did nothing more than struggle to get by and provide for their families. The mundane struggles of our forebears gave us a future. That is certainly worth celebrating.

In order to celebrate our past, is it really necessary to know who is descended from whom? The history of our culture is written in the sometimes-mundane, sometimes-heroic stories of our families. The stories are important and they belong to us all.

Perhaps our particular ancestry should not be called a family tree because it is not an independent structure with its own unique roots. It is rather just one branch, not all that different from the others, on the larger tree of the one human family.