Why Americans All Believe They Are 'Middle Class'

A taxonomy of how we talk about class and wealth in the United States today

Last week, President Obama went on the road promoting an economic agenda for the middle class. As expected, John Boehner and other Republicans fired back by charging Obama with “squeezing the middle class.” It’s not even an election year, yet “middle class” is hotly contested linguistic real estate. But nobody seems to know what this term means.

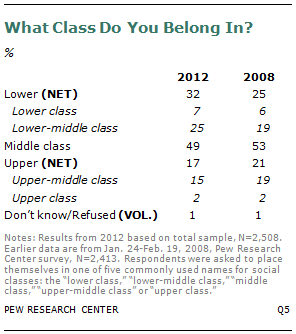

“Middle class” remains our favored self-designation, although the percentage of Americans who select it fell from 53 percent in 2008 to 49 most recently, according to Pew Research. As a friend’s high-school teacher loved to say, “The great thing about America is that everyone can be middle class.” Good thing she wasn’t teaching math.

Given this popularity, it is no mystery why “in the interest of the middle class” now beats “for the children” as political cliché. The puzzle is why so many who do not fit the category (as median family income reported as just above $50,000 defines it) believe they do. Why does the description “middle-class nation” continue to feel appropriate, desirable, or both?

Researching how people’s unconscious assumptions affect their perception of economic issues, I explored the linguistic dynamics behind the term “middle class,” especially in comparison to other economic groupings. In the Corpus of Contemporary American English, a database of more than 450 million words from speeches, media, fiction, and academic texts, among the most common words (excluding conjunctions and prepositions among others) co-occurring with “middle class” we find “emerging,” “burgeoning,” “burdened,” and “squeezed.” These tell us what happens to this grouping. Absent are quantitative terms or descriptors for what life is like within this category. In fact, in common usage, we rarely hear about actual people named within it; middle class may as well describe a grouping of potted plants or pop cans. There’s little here tied to income or lifestyle.

Conversely, statements about “the wealthy” co-occur with terms like “investors,” “businessmen,” “patrons,” “owners,” and “donors.” What these words indicate is a sense of sources of income and, by extension, the amount compensated. The wealthy, in our language, aren’t acted upon but rather act as human members of a group who get things done and pay themselves to do it.

"Poor," once the meaning of low quality is filtered out, comes with “guy” and “girl” but also “homeless,” “sick,” “plight,” “needy,” and “suffering.” Those descriptors provide a sense what it’s like to be in this group day to day, and they make pretty clear it’s made up of people who aren’t allowed any or much income.

Poking into usage also confirms that Americans are relatively skittish about mentioning class. Contrasting databases of text from U.S. and UK sources, we find that Brits use “upper class” and “lower class” more readily; we prefer “wealthy” and “poor.” Yet we grant “middle class” plenty of airtime. This suggests it’s a frozen phrase, no longer rooted in the meaning of component parts that ought to designate economic status between two others. Instead, middle class has become a status, a brand – a label you opt to adopt.

From Real Housewives to pop stars, extreme wealth is on display all around us. Seeing this, Americans imbibe ideas of what life as a rich person means. And most folks, even in the 1 percent (that is, with incomes above about $500,000), can’t keep up with the Kardashians. They conclude they are not wealthy, so they tag themselves middle class. We’re far less keen to have the poor in view. Nevertheless, whether via images of bread lines or real life panhandlers, we have some sense of life without means. If homelessness is the salient exemplar, people are unlikely to say they’re “poor.”

Cognitive science teaches us that we learn to make sense of the world by putting things into categories. From the simplistic (edible or not) to the sophisticated (possible spouse or casual fling) grouping elements is part and parcel of our processing. In order to determine what category something fits into and thus what it is, we often rely on considering what it is not. Sometimes, these designations are easy: A smart phone and a rotary dial both count as telephones. But categories of great social significance are subject to interpretation and change with the times. Is that boy “spirited” or “ADHD”? Labels, once stuck, can change perception and policy.

Not finding popular depictions of wealth and poverty similar to our own lived experiences, we determine we must be whatever’s left over. Picking “middle class” is easy enough to do because, again, the language doesn’t present much to go on in terms of what this label describes.

The remaining economic component for all of our class designations isn’t income but stuff you can buy. One common synonym for rich and poor is the haves and have-nots. But consumer goods once deemed luxuries, like cellular telephones and televisions, are now common possessions. This means that even as employers held tight to the gains our productivity generated by keeping real wages at 1970s levels, we sent women into the workforce, labored longer hours, and used new debt products to indenture our way to some happiness. Thus, our stand-in to signify class status – purchasing power – papers over the fact that by income, benefits, and lifestyle standards many of us had long left behind a middle-class existence, even as we clung to the moniker.

Peering behind the once iconic picket fence surrounding a house, we see what “middle class” used to mean. The mortgage was close to paid off; the car loan settled. This feat was accomplished on a single income that came with health care plus pension and enough for domestic vacations and college.

Today, we are left with mere symbols, but these turn out to muddle, not mark. Being in the middle class once guaranteed choices and life without fear that the unexpected would prove catastrophic. Now, this is far from the case. Politicians of all stripes will continue to claim allegiance to the middle class, but that’s just because they’re hoping we don’t notice it’s a brand without a product.