In early 2014, Google made an interesting announcement. The company had a new product in the pipeline, one that could change the way we interact with computers. Google showed a prototype of the technology built into a Nexus phone. Dubbed Project Tango, it allowed the device to gain awareness of the space it was in, and to do so far more precisely than anything seen previously.

Google pre-announced the technology, it seems, because it didn’t really know what to do with it.

The Guardian’s product and service reviews are independent and are in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. We will earn a commission from the retailer if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

Google is no stranger to moonshots. It regularly announces projects and plans far in advance of them being ready for the market. The rationale for these pre-announcements is usually that, at some point, they have to be tested in public. Think self-driving cars, internet balloons and delivery drones. But Project Tango was different: the company pre-announced the technology, it seems, because it didn’t really know what to do with it.

Alongside the announcement came a call for suggestions from developers, who were offered one of 200 early prototypes. Google provided prompts for potential game ideas (“Imagine playing hide-and-seek in your house with your favourite game character, or transforming the hallways into a tree-lined path”) and for potential applications (“What if visually impaired people could navigate unassisted in unfamiliar indoor places? What if you could search for a product and see where the exact shelf is located in a superstore?”), but ultimately it left it to the developers to suggest what they would do.

Build first, ask questions later

Google’s approach – to come up with a technology, and then work out what to do with it – has good pedigree in the industry. When Apple’s Steve Jobs revealed the iPhone in January 2007, some of the ways it would go on to change the smartphone industry were clear from the start. The full-size, full-colour capacitive touchscreen was a focus of Jobs’s presentation, and instantly became the norm across the industry. So too did the concept of abandoning the poky “mobile web” for the full internet, displayed in full on screen (using the fancy pinch-to-zoom method which would soon become ubiquitous).

But other features of that first phone which would become almost as important were buried, mentioned in passing or not at all. Chief among them was the presence, from the very first iPhone onwards, of an accelerometer – a physical sensor that allowed the phone to determine its relative motion and position.

On stage, the accelerometer was highlighted with a niche use: if the phone was tilted from portrait to landscape, or vice versa, the content would rotate to fit. This feature, too, has gone on to be everywhere, and it’s an interesting example of the attention to detail in the original iPhone. Everything the accelerometer did in the first version of the iPhone operating system could have been replaced with a single “rotate” button, but it wasn’t, because that would have been terrible.

For the first year of the iPhone, that was pretty much it for the accelerometer. A few websites followed Jobs’s short-lived dictum that “the best apps are on the web”, but for the most part, the component was used solely to check whether or not the phone was in portrait or landscape orientation. Then, in July 2008, alongside the iPhone 3G, the App Store made its debut. Suddenly, all the data coming from the accelerometer was no longer only usable by Apple; third party developers had their time to shine.

And they did. Canny usage of the accelerometer rapidly became one of the defining characteristics of mobile-first apps, particularly games. From Cube Runner, a simple arcade game launched alongside the app store by independent developer Andy Qua, to popular hits like Doodle Jump and Real Racing 3, the accelerometer rapidly proved to be far more than just a tool for working out how the user was holding their phone.

As smartphones developed, a similar tale occurred again and again: a feature introduced for a minor, specific purpose would be blown open by developers. The compass, first included in the iPhone 3GS to enable mapping apps to rotate with the user, would go on to become an integral part of alternate reality apps such as Star Chart.

The iPhone 4 included the line’s first front-facing camera, a feature that had debuted on dumbphones a decade before. On the iPhone, it enabled FaceTime, Apple’s video-calling service – but it also basically created the concept of the selfie. On Android devices, the front-facing camera would soon be used for “face unlock”, a feature which lets the phone recognise its user and unlock without needing a passcode.

As the market has matured, smartphone manufacturers have been increasingly happy to rely on third party developers to give new features their killer application. But none, so far, have taken the final step, of creating the capability explicitly without knowing what it’s going to be used for.

Project Field of Dreams

Google’s Project Tango is the closest we’ve come to a “build it, and they will come” attitude in tech. It takes everything that is already revolutionary about the progression of smartphones as tiny hubs for every sensor imaginable, and doubles it. The goal is no less than letting a phone or tablet have an understanding of what the real world is actually like, as accurately as you or I.

At the heart of that intention is a panoply of sensors studding the outside of the prototype devices. As well as everything you would expect from a smartphone – a camera on the back and front, and a gyroscope and accelerometer – the Project Tango devices have extra input. Accompanying the rear camera is an infrared emitter, constantly emitting an invisible grid across the world, and an infrared camera, picking up the reflections the grid makes.

If that sounds familiar it’s because it’s similar in principle to how Microsoft’s Kinect system works. But rather than being pointed at you, it’s pointed at the wider room. That’s matched with super accurate versions of internal sensors common in other phones, such as the accelerometer, gyroscope and barometer (which measures air pressure, but can also be used to determine altitude), to provide the phone with everything it needs to build up a super accurate map of the world and its location within it.

A year and a half after it was announced, I went to see the kit as it stands today. The hardware has gone through a few iterations – the latest version of the development kit is now in a tablet form factor, rather than a mobile phone, and in August it went on sale to developers in the UK for the first time – but it’s what it does which immediately grabs the attention.

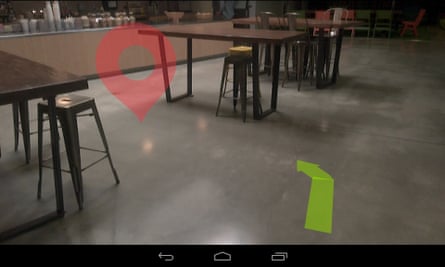

Handed a prototype, I’m run through a raft of games and tools, all of which demonstrate the hardware’s uncanny understanding of where it is and what the world around it is like. And uncanny is the right word: a Minecraft homage, where I stare through the tablet into a virtual world built out of bricks, doesn’t feel like a game. It really does feel like there’s another world, mapped 1:1 on to ours which I’m interacting with through the screen.

The effect is only magnified when the developers strap the tablet to deconstructed Nerf gun and tell me to pull the trigger to shoot enemies. An alternative-reality game begins, and again the tablet maps perfectly to the real world. More than simply rotating to see behind myself, I can aim up and down, duck, or even (with care) sprint across the room.

But the most impressive examples are those being built by the developers who also had early access. Another alternative reality game lets me physically step through a portal into the Jurassic period – at least until a T Rex chomps down on me, bringing the demo to a close.

Or perhaps “impressive” is the wrong word. In the same way as the plethora of sensors bristling on the outside of an iPhone only really became truly groundbreaking when their use became utterly frictionless, the examples of Project Tango in action that most seem like a glimpse of the future are almost invisible.

Google’s team have produced a demo that lets you simply use the phone’s camera as a measuring tape. Tap two points on the screen, and it will calculate the distance between them.

Scale that idea up a bit, and you end up with just one use that could prove transformative. A logistics company that’s worked with Google Now has a tool set up that lets it point the device at items to be transported, and see them tessellated into a container.

After almost 18 months in development, the first Project Tango devices made by Google partners such as Intel are now starting to filter out into the market. Eventually, Google envisions the technology moving beyond phones and tablets to other devices, and Larry Yang, the project lead for the tech, says he could see drones as a fertile ground for the next generation of space-aware tools.

But in the immediate future, the test will be whether or not it gets included in consumer- and enterprise-grade phones and tablets. Google has built it – will they come?

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion