This Is Janet Yellen's Biggest Challenge

Forward guidance might only be as good as the data is bad.

The Fed is trying to put back with the right hand what it's taking away with the left. But it might need to use both together if it's going to speed up the recovery.

Ever since Lehmangeddon, the Fed has been stuck in a brave, old monetary world where even zero interest rates aren't enough to jumpstart the economy. It's a world that, outside of Japan, we haven't seen since the 1930s. And one that the Fed has tried to find a way out of in fits and starts. By late 2012, it had settled on a two-pronged strategy to do so: purchases and promises. The Fed purchased $85 billion of long-term bonds a month with newly-printed money, and promised to keep rates at zero at least until unemployment fell below 6.5 percent or inflation rose above 2.5 percent.

But now these programs are winding down, and we still haven't gotten the catch-up growth that's always a day (or 6-12 months) away. The Fed started this return to normalcy last May when Ben Bernanke said that it would soon start reducing—or, in financial lingo, "tapering"—its bond-buying. Investors didn't like this surprise, but the Fed didn't like the one it got either. Even though its forward guidance hadn't changed at all, the taper talk made markets expect the Fed to start raising rates much sooner than before. In other words, markets didn't distinguish between the Fed's purchases and promises. That's because the purchases are what made the promises credible, the Fed putting its money where its mouth was.

So how much are the Fed's promises worth today? Well, more than you might think, though there are still a few difficulties. First, the Fed has started tapering, so it needs to convince markets that this doesn't change its forward guidance. Second, joblessness has fallen fast even though we haven't added jobs fast—because people are giving up—and that's made the Fed's unemployment threshold all but useless.

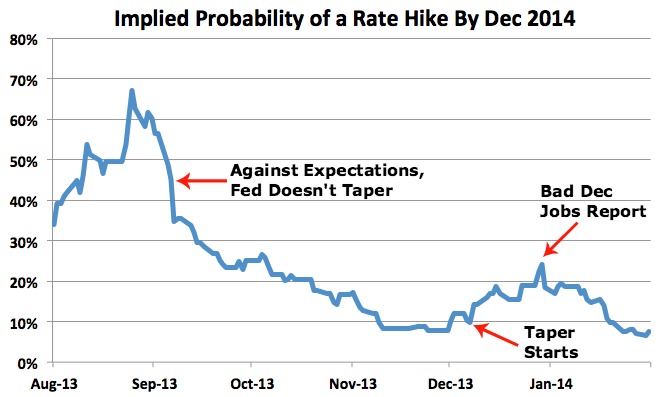

You can see how much the Fed's guidance has and hasn't worked in the chart below. The blue line shows what percent chance markets think there is that the Fed raises rates by December 2014—well before it says it will now—based on futures contracts. It turns out that what the Fed does and the economy does matter more than what the Fed says.

The big story is the decline and massive fall of how much markets think the Fed might raise rates soon. But that's not the only story. Here are the three big takeaways:

1. It doesn't seem like it should have mattered whether the Fed tapered in September or December, but it did. That's because, as Paul Krugman explains, it told us something about the Fed's character. Suppose, for example, that the Fed had tapered in September, like markets thought it would, despite some so-so economic data. That would have told markets that the Fed was determined to pull back no matter what, that it was more hawkish than we thought—on QE and rates hikes, too.

That's why the Fed's taper talk made markets expect it to raise rates sooner. Investors thought the Fed was telling us that it had changed who it was. But then, after all this build up, the Fed didn't change, it didn't taper in September. Markets stopped thinking that it would raise rates any sooner than they'd thought before.

2. The December taper didn't seem like that big a deal, but take another look. The Fed tried to learn its lesson from before. It assiduously explained that just because it was purchasing less didn't mean it was promising less. The opposite, actually. This time, it tried to offset fewer purchases with more promises. To put back monetary stimulus with its right hand that it was taking away with its left.

Specifically, the Fed said that it would probably keep rates at zero "well past" the time that unemployment falls below 6.5 percent—especially if inflation stayed so far below target. But the Fed's hawkish actions spoke louder than its dovish words. Before the taper, markets thought there was a 10 percent chance of a rate hike by December 2014; afterwards, they thought there was a 20 percent chance.

3. Then the economic data started looking ugly. Maybe it was just the weather, maybe not. Regardless, markets started to worry that the recovery would stay stuck in stall speed—which would give the Fed no reason to raise rates. Markets went from thinking there was a 25 percent chance of an end-of-year rate hike to just a 7.5 percent chance. That's even lower than it was before the taper.

But that's not a communications success. It's an economic failure. If the economic numbers had kept looking better, markets might have kept betting on an earlier-than-expected rate increase. Forward guidance might only be as good as the data is bad.

Here's the Fed's problem, in two sentences. Its promises don't work as well without its purchases, especially when the economy is looking up. It can try to get around that by promising more when it purchases less, but markets might not believe that—which could keep us stuck in the same good-but-not-good-enough recovery.

Maybe we should try doing more instead of worrying about doing more, and never doing enough.