Thoreau: An Editor's Nightmare

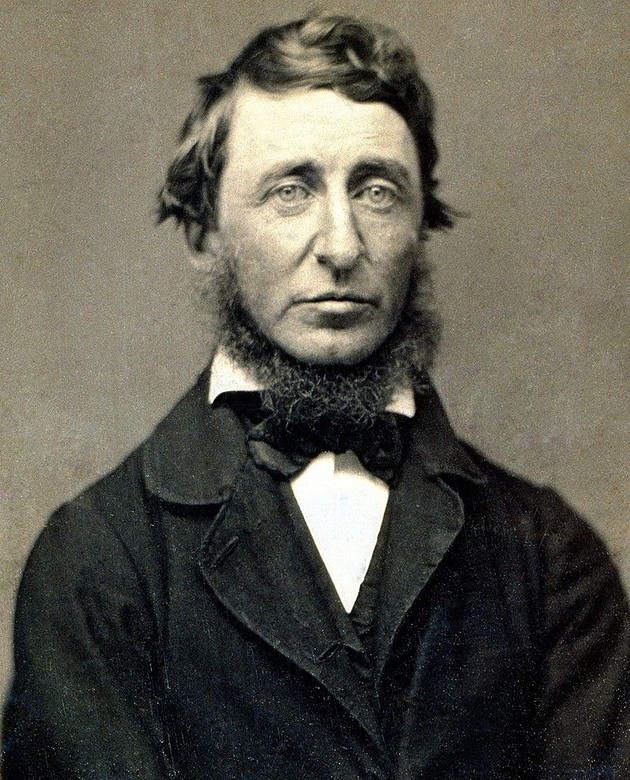

Philosopher, poet, and pond-dweller Henry David Thoreau occupies an esteemed place in America’s imagination and reading lists. But earlier this week, The New Yorker’s Kathryn Schulz wrote a scathing takedown of the writer, calling him “self-obsessed: narcissistic, fanatical about self-control,” sparking debate across the Internet. So far, my favorite characterization of Thoreau is “a genuine American weirdo,” written by Jedediah Purdy in a rebuttal to Schultz. One reader wrote in response: “I like some Thoreau. Lots of authors are dicks, just like artists of many types. Doesn’t mean I can’t enjoy their work.” Another reader:

I love Thoreau. What is piggish about living simply and deliberately, not taking more than you need, respecting individual rights, being anti-slavery and practicing Civil Disobedience? I think a lot of it comes down to extroverts being generally put off by anyone who dares to be an introvert.

Email your thoughts here. The Atlantic has a unique stake in this debate, since Thoreau was one of the earliest contributors to the magazine, publishing a number of essays here in the last years of his life. And if that experience is anything to go by, you probably wouldn’t have wanted to be his editor.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, one of The Atlantic’s founders, was also a buddy of Thoreau’s. (Emerson published a tribute to his friend, after his death, here.) As Ellery Sedgwick, the magazine’s eighth editor, writes in A History of The Atlantic Monthly, Emerson encouraged Thoreau to submit a narrative about life in the Maine woods. Among the casualties of the editing process was a single, not-especially-remarkable sentence.

But Thoreau, ever meticulous, was affronted to discover that deletion in the published version of his piece. He wrote an angry letter to the The Atlantic’s founding editor, James Russell Lowell, in June 1858:

I have just noticed that that sentence was, in a very mean and cowardly manner, omitted… I am not willing to be associated in any way, unnecessarily, with parties who will confess themselves so bigoted and timid as this implies. I could excuse a man who was afraid of an uplifted fist, but if one habitually manifests fear at the utterance of a single thought, I must think that his life is a kind of nightmare continued in broad daylight. It is hard to conceive of one so completely derivative. Is this the avowed character of the Atlantic Monthly?

Luckily, thanks in part to a new editor, James Thomas Fields, The Atlantic convinced Thoreau to publish several more essays in 1862, right before he passed away. Whatever you think about the man himself, these essays—many autumnal-themed—are lovely glimpses into Thoreau’s pastoral world. As he wrote in “Autumnal Tints,”

October is the month of painted leaves. Their rich glow now flashes round the world. As fruits and leaves and the day itself acquire a bright tint just before they fall, so the year near its setting. October is its sunset sky; November the later twilight.

Also see “Wild Apples,” a portrait of the tree that bears the “noblest of fruits”, and the famous essay “Walking,” in which Thoreau meditates on the virtues of a mind and body free to wander wherever they please.