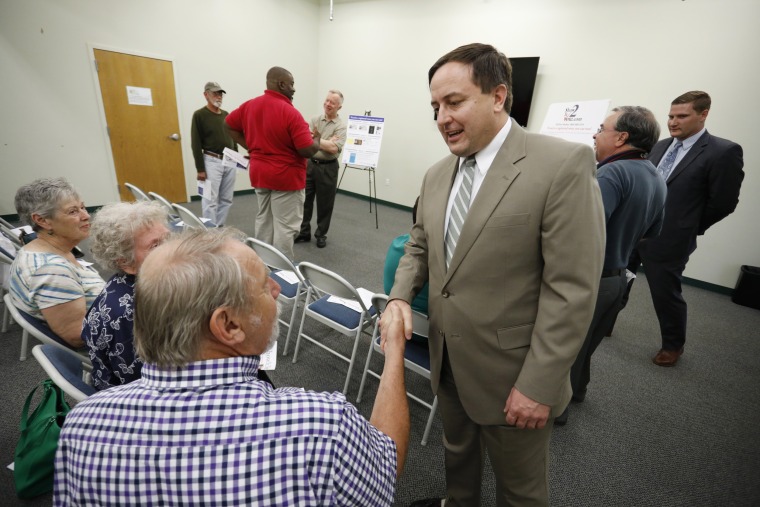

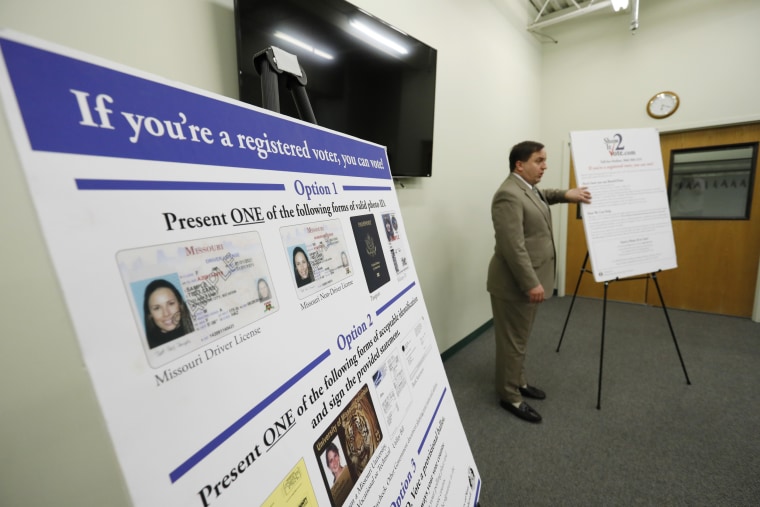

MARSHALL, Mo. — Paul Gieringer let Missouri Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft talk for half an hour, explaining the state's complicated new voter ID law to a crowd of two dozen at the local community center, before raising his hand.

"How many cases of voter fraud have there ever been in Missouri?" Gieringer, 61, asked.

"We know it's happened," said Ashcroft, 44, noting that he didn't have any hard numbers, although he cited a 2010 incident in which a couple claimed a false address on their voter registration forms to vote in a primary election. "How many are an OK number? Is it OK to have one or two?"

The Republican secretary of state didn't mention that the new law he's traveling the state to promote — aimed at combating voter impersonation — wouldn't have stopped the couple, a fact his office later confirmed.

"He brought up the red herring of voter fraud," Gieringer later told NBC News.

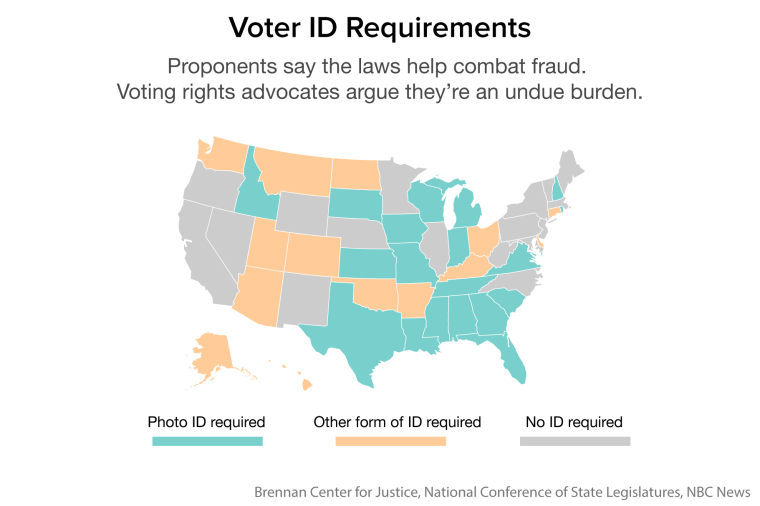

Missouri is one of eight states that have passed or are implementing laws with more rigorous voter identification requirements this year.

Fueled by President Donald Trump, who has claimed, without evidence, that voter fraud deprived him of the popular vote in 2016, there's more energy behind election legislation than ever before. Trump has appointed a federal commission to find and combat voter fraud — a problem experts say doesn't exist on a large scale.

"With President Trump, voter fraud is a crime that's a high priority," the commission's vice chairman, Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach, said in an interview.

Trump's stance is already playing out in court: His Justice Department, which under President Barack Obama fought Texas over its voter ID law, filed a motion Thursday supporting the latest version of the law. After nearly a decade of raising alarm about alleged vote fraud, Kobach, a leading advocate of tough voter requirements, said it's heartening to have the muscle of a federal commission and the Justice Department tackling the issue.

But it is the states, where Republican-controlled legislatures are using more sophisticated tactics than they have previously, that are poised to have the most immediate effect in the 2018 midterms and the 2020 presidential election.

With turnout in the United States already low — 55.7 percent of voting-age Americans cast ballots in 2016 — critics say voter ID legislation disproportionately affects minorities, low-income Americans and younger voters. The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University has estimated that as many as 11 percent of Americans — 21 million of them voting age by 2000 Census data — were without photo IDs, while 4.5 million more have IDs that may not reflect their current names or addresses.

Some studies have found that ID laws depress turnout: One study that controlled for outside effects found that they depressed turnout among both Republicans and Democrats but hurt Democratic and minority turnout the most, while other analysis has noted that turnout can be influenced by everything from the weather to that year's batch of candidates, indicating that the effect of voter ID requirements is hard to measure.

Opponents say the real intention is not to guarantee the integrity of elections but to disenfranchise certain groups, those that often vote Democratic.

Texas and Missouri are requiring affidavits — legal documents that voters without the required ID must first sign to cast ballots. Any falsification is a felony.In Georgia, voter registration forms must exactly match other state data, which means a data error or a misplaced hyphen could derail voters. Iowa has mandated that voter rolls be purged of suspected non-citizens.

Proponents of such laws insist that they are not burdensome and are needed to ensure elections are on the up and up.

"Voter impersonation does occur. Does it occur on a large scale? No," said Arkansas state Sen. Bryan King, a Republican who wrote the state's 2013 voter ID law, which was later ruled unconstitutional. "These type of situations can be very small, but they can be very impactful. It can affect elections."

King led a successful effort this year to get a referendum on the 2018 ballot that will ask voters to amend the state Constitution to mandate photo IDs. He points to one of his own electoral wins, by 35 votes, as an example of how important such a requirement can be.

Arkansas state Sen. Joyce Elliott, a Democrat, disagrees. In an interview with NBC News, she called the state's voter identification law a "different kind of poll tax," the fees many Southern states charged to disenfranchise black voters decades ago.

"As a little girl, just seeing my family and the older people in my community, I used to hear them whispering about poll taxes. I saw how they thought and how intimidated they were about voting," Elliott, 66, said of her upbringing in Jim Crow-era Arkansas. "Whether we think we're repeating it or not ... we really are."

Elliot grew up in the civil rights movement — the Voting Rights Act, barring poll taxes and other barriers designed to keep minorities from voting, was passed when she was 14 — and she said she never thought she'd have to address the issue again as a politician.

"Those things are just tattooed in my lexicon in thinking about what's right and fair for people," she said. "It's immensely taxing to think that we'd go back to revisiting something I thought was fixed — fixed in our souls."

New laws, new restrictions

There is no evidence of widespread voter fraud in Missouri, or anywhere else, and yet voter fraud legislation has never been as popular as it is now.

At least 99 bills to restrict access to the polls have been introduced (or have been carried over from previous sessions) in 31 states this year; that's already more than double the number last year, according to data compiled by the Brennan Center. Voter ID — requiring voters to prove who they are with identifying documents — is the most common requirement, but changes to the voter registration process, such as asking people to prove their U.S. citizenship, are a close second.

"The problem is when a law prohibits a certain class of people" from voting because they lack "access or ability" to obtain one of the approved forms of identification, said Myrna Pérez, who leads voting rights efforts for the Brennan Center. "They offer our society very little public benefit, in that they only stop an incredibly rare type of voter fraud."

Six state laws have passed this year, double the number in the previous two years, while two more are being implemented. Six of the eight came after courts stepped in to stop past efforts.

A few examples: A decade after Missouri's highest court threw out a voter ID law, the state is implementing another. In North Dakota, after a court ruled last summer that a voter ID law was disenfranchising Native Americans, the Legislature added tribal IDs to the list of acceptable identification this year. Texas' Legislature approved a law this summer that it hopes will pass muster with the federal judge who said an earlier law was intentionally discriminatory.

In a new strategy to fend off legal challenges, some of the laws and bills working their way through state legislatures seek to shift the financial burden off voters — something Missouri models with its offer to pay for both photo IDs and underlying documents for voters who lack them — but they can also create other barriers that can be just as deterring, according to opponents.

The affidavits in Texas and Missouri carry criminal penalties if they're found to be inaccurate. In Missouri, the affidavit asks voters to swear their identities "under penalty of perjury." Anyone suspected of fraudulently using the form may be photographed by poll workers, as well. Conviction for filing a false form means a felony record in both Missouri and Texas, where it could mean up to two years in jail. In Missouri, it could also mean a loss of voting rights.

Ezra Rosenberg, co-director of the Voting Rights Project at the nonprofit Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, who has been fighting Texas' attempts to institute photo ID for five years, said the intention of harshly worded affidavits is to intimidate. Texas' court-ordered use of an affidavit to vote in the last election caused confusion, he added. There were questions about whether someone who lost an ID could sign an affidavit — designed for those who do not have ID — in order to vote.

"It can only have the effect of diminishing the number of people who vote, make people a little scared or uncertain, particularly when they have to sign something in order to vote," he said.

Meanwhile, several states in which election laws have run afoul of the courts have come up with another new way to gird their latest efforts against legal challenges: amending their state constitutions to mandate voter ID. In lieu of evidence that voter fraud threatens elections, a constitutional call for photo ID at the polls sturdies their legal footing. Advocates say this makes the laws harder to fight.

Missouri's voter ID law is supported by a constitutional amendment; 63 percent of voters approved it in November. Ashcroft told voters that the constitutional amendment was fundamental to the state's reinstating a photo ID law after the state's Supreme Court had ruled it unconstitutional in 2006.

Arkansas lawmakers passed a bill this year that will ask voters to approve a voter identification amendment in 2018, and Oklahoma and Nebraska are weighing similar measures.

"Previous attempts were sort of stymied by that lack of requirement in the constitution," Sophia Lakin, a lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union, said of Missouri's effort. The ACLU is backing a lawsuit against the state's implementation of the law.

The campaign to fight back

Texas had the toughest voter ID law in the nation when U.S. District Judge Nelva Gonzales Ramos, who declared it discriminatory, struck it down ahead of the 2016 election. She later ruled that it was discriminatory in intent.

The state, which has more than a half-million registered voters without the required identification, hurried a new bill through the Legislature, arguing in June in front of the judge that they had fixed the previous law's problems. Voting rights advocates asked to have the law, which they say is rooted in the framework of the original bill, thrown out. They also called on the judge to subject any new election laws to federal pre-clearance, the mechanism that states with histories of discrimination had been subject to before the Supreme Court's 2013 ruling on the Voting Rights Act.

The suit, which is continuing, is one of 15 major lawsuits pending in 11 states, according to the Brennan Center. Opponents of additional voting requirements say that in the wake of the Supreme Court's decision — which gutted much of the federal government's ability to enforce the Voting Rights Act — there has been a frenzy of election changes and proposed legislation, forcing them to fight more suits in court than ever before, which can be costly and a drain on manpower.

"We've just seen local jurisdictions and the states enacting regulations and legislation that would not have survived under the Voting Rights Act," said Julie Houk, a lawyer for the Lawyer's Committee for Civil Rights Under Law monitoring Georgia's elections, citing a recent proposal to shutter 17 polling places.

"It's become very sophisticated. It's just a matter of whether courts are going to let jurisdictions get away with it," she added.

The Supreme Court recently refused to reinstate a North Carolina voter ID law that a lower court overruled as discriminatory, and it has agreed to hear a case on Ohio's voter roll purge, as well as another on alleged Wisconsin gerrymandering, in its fall session. Those rulings could set major legal precedents on voting rights.

The hunt for fraud

Despite the recent flurry of activity, talk of voter fraud and efforts to combat it are nearly two decades old. For Ashcroft, it's also a family affair.

His father, John Ashcroft, led the first national search for fraudulent voters as President George W. Bush's attorney general. John Ashcroft's Justice Department found little evidence of it after five years of hunting, yet the federal government is at it again.

Trump, who has claimed without evidence that as many as 5 million illegal votes caused him to lose the popular vote to Democrat Hillary Clinton, created a voter integrity commission in the spring and tapped Vice President Mike Pence and Kobach, one of his informal immigration advisers and an Ashcroft family friend, as co-chairmen.

Kobach, who is running for governor of Kansas in 2018, said he believes illegal voting by non-citizens is a "bigger problem" than current evidence suggests.

"A priority of the commission will be to make public any that is discovered and uncovered through having hearings, asking states to provide what data they have, and federal agencies," he said. "We just don't have the facts."

After Kobach, on behalf of the voter fraud commission, asked the nation's secretaries of state for data on their voter rolls, many protested, citing concerns over privacy and how such data will be used.

RELATED: 45 States Refuse to Give Voter Data to Trump Panel

The Brennan Center points to Kobach's own 2013 review (since taken offline) of 84 million votes cast in 22 states, where he found just 14 instances of fraud sent on to prosecutors, according to contemporaneous reporting.

Meanwhile, a large number of academic reviews disproves widespread voter impersonation. A researcher at Loyola University in Los Angeles reviewed a billion ballots and found 31 cases of voter impersonation, while an Arizona State University study found 10 cases in a review of a decade of ballots. Government investigations have similarly found few cases to prosecute, with just a handful of convictions nationwide. In rulings against state voter ID laws, courts have routinely cited a lack of evidence.

Back in Marshall, Missouri, Mary Williams, 67, the African-American pastor of Salem Evangelical Church, is worried that the law will disenfranchise her friends and neighbors.

Standing in the community center after Ashcroft's voter education event, she remarked that it's already hard enough to vote where she lives. There used to be four polling places, but now there's one. There are no sidewalks, and there is no public transportation.

"It means that less people in general are voting," she said. "The whole photo ID thing is a solution to a problem that doesn't exist."

Graphic research by Ariana Brockington.