Shortly before lights-out, a 20-something sleep technician named Dara rigs me up with a bewilderment of wires and sensors: half a dozen electrodes on my crew-cut cranium; air-pressure gauges beside my nostrils and mouth; heart and lung monitors across my chest; and motion detectors by my eyelids and jaw and on my legs. For the remainder of the night, my every brain wave, breath, heartbeat, eye flicker, tooth grind, and leg jerk will be recorded for analysis.

The purpose of all this high-tech surveillance equipment? To catch a thief: a Freddy Krueger-type bogeyman stealing my breath and libido, my vitality and brainpower—and potentially, perhaps even my life itself.

Physicians call the culprit "obstructive sleep apnea," a syndrome characterized by the repeated collapse of a person's airway during sleep. Breathing becomes extremely labored and can stop altogether for as long as a minute. As oxygen levels drop, adrenaline and blood pressure surge.

Eventually the deepening desperation for air provokes a momentary awakening—what sleep doctors term a micro-arousal. This lasts just long enough for the apnea victim to suck in a lungful of air and resaturate the bloodstream with oxygen, and then to immediately slip back into shallow, nonrestorative sleep. With sleep, of course, inevitably comes the next round of airway relaxation, collapse, and suffocation.

The result: a raft of health problems, including dangerously elevated risks of diabetes, heart attack, and stroke.

(A lack of sleep can damage more than just your health. Check out how Insomnia Really Hurts You.)

Of the estimated 4 percent to 6 percent of American men suffering from sleep apnea, most don't know the danger they're in. Indeed, many actively deny that they even could be victims.

For me, such manly denial isn't just pride. Over the years, I've heard that the typical sleep apnea sufferer is a fat guy with a turkey wattle neck and stentorian snoring.

My BMI is 24, my neck the sort that conjures images of pencils and geeks. In recent decades, my poor man's harem of bed partners have agreed that I snore only occasionally, and lightly at that.

What's more, 3 weeks ago I swam a lifetime personal record in the 200-yard freestyle, smashing my college time from 35 years ago. How can a guy starved of breath each night accomplish that?

"It's a waste of money," I tell Dara. Tonight's lab visit will cost over $2,000. If I hadn't already met my deductible, I'd be tempted to rip the wires off my body, apologize profusely, and decamp.

"Oh, you might be surprised," she says. "I once had a 150-pound guy and a 500-pound woman in on the same night. I was sure he'd test fine and she'd have horrible apnea. But he had a severe case, and she was the cleanest breather I've seen yet."

Tom Zehmisch is a big part of why I'm being tested. Five years ago at a national swim meet, I shared a room with Tom, a lean and superbly fit triathlete. Tom had the body type that you could see gracing the cover of this magazine—the diametrical opposite of what doctors have dubbed the Pickwickian syndrome.

Named after a character in Charles Dickens's The Pickwick Papers, Pickwickians suffer from obesity, chronic grogginess, bansheelike snoring, and cardiac complications that have been triggered by years of low oxygen during sleep. In the minds of many laymen and physicians alike, the majority of sleep apnea sufferers are Pickwickians.

Of this laundry list of symptoms, the only one Tom had was snoring. His snoring was so loud, in fact, that I ended up moving to another motel across the street after the first night, and even then I could still hear him. Tom was convinced I was exaggerating his decibel levels. In hindsight, I only wish I had made the case more forcefully.

Four months after the meet, Tom died of a heart attack during the biking leg of a triathlon. He was 46.

"There are athletes everywhere who have sleep apnea," says W. Christopher Winter, M.D., medical director of the Martha Jefferson Hospital sleep medicine center in Charlottesville, Virginia. "Not only does the apnea affect their athletic performance, but it is extremely hard on their cardiovascular systems as well."

Though heart-related deaths from untreated sleep apnea usually occur during sleep, chronic stress on the heart can leave victims vulnerable during strenuous athletic events. Over time, for instance, many people experience pathological thickening of their heart's right ventricle, causing it to struggle to pump enough blood to their lungs.

The bodies of other sufferers react to nighttime oxygen deprivation by manufacturing extra red blood cells, the same effect seen in high-altitude dwellers. It's a mixed blessing: increased oxygen carrying capacity, but at the cost of "sludgy," harder-to-pump blood.

Apnea can even spur the growth of collateral heart vessels, something seen in heart patients whose coronary arteries are clogged with plaque. Unfortunately, these new vessels are rarely sufficient to compensate for a clogged artery for very long, if at all.

"Athletes' hearts are pushed by their sport during the day and by their apnea at night," says Dr. Winter. "A time for rest and recovery now becomes a time that puts their health in peril."

It's this unremitting cardiovascular stress that worried Randy Nutt most about his own sleep apnea diagnosis.

Nutt is the founder of Aqua Moon Adventures, a company that organizes long-distance open-water eco-swims in exotic locales from Bonaire to Bermuda. A marathon swimmer himself, Nutt has circumnavigated both Miami Beach (21 miles) and Manhattan Island (28.5 miles).

"It really scared me that something could go wrong with my heart in the middle of the ocean somewhere," he says, recalling the period between when he was diagnosed with sleep apnea and when he received treatment. "Stressing your heart with aerobic training is good for it. But gasping for breath 37 times every hour you're asleep is not."

Between these good-cop, bad-cop cardio "workouts," Nutt wondered how long his heart could hold out.

John LeCornu, a former Coast Guard boatswain mate, realizes today that he faced the same risks.

"Thinking about it now, it was like playing with fire," he says about his daily workout routine, which included a 10-mile run, a 2-hour gym session, and marathon basketball games in an adult league.

Despite his considerable fitness level, LeCornu's blood pressure was 185/115, which he attributed to a family predisposition to hypertension. Three different prescription medications could not budge his pressure below 160/110.

"My doctor was ready to diagnose me with an anxiety disorder," LeCornu recalls, "when I happened to mention that I also felt tired all the time. I'd assumed my tiredness was normal because of the exercise, but my doctor said working out usually gives you more energy, not less."

A sleep study revealed severe sleep apnea. "I thought I was putting my heart through its paces during the daytime," LeCornu says. "But the real stress, it turned out, was happening at night when I thought my body was resting and recuperating. In retrospect, my cardiovascular system was working on overdrive 24/7. I was headed straight toward stroke central."

I guess I do have a few symptoms of sleep apnea. Sometimes, for instance, I wake up marinated in sweat, my head pounding as if I had bounced it on cement. Sleep erections have become so rare that when one does occur, I'm tempted to note it in red letters on my desk calendar. But the worst symptom by far is daytime sleepiness so profound that I wonder if there's chloroform in my pillow.

Pathological grogginess nearly cost me my swimming PR. In an earlier race I was so sleepy my eyes involuntarily shut, causing me to crash into the lane rope. During the 200, I mentally chanted eyes open the whole time.

Dara flicks the light switch off, signaling that the time for eyes closed has mercifully arrived. The next thing I know, she's waking me up at 4:45 a.m.

"Do I have it?" I ask, still confident of a clean bill of sleep health.

"I'm not allowed to diagnose you," she says, "But off the record, definitely yes."

At first I think she's joking. Then she shows me how I stopped breathing 102 times, and how the oxygen in my blood fell to levels typical of climbers at a Mount Everest base camp.

(Why is sleep so essential? Find out how our brains are wired for rest with The Science of Sleep.)

More and more, sleep apnea's threat to highly active men is being taken seriously by medical researchers.

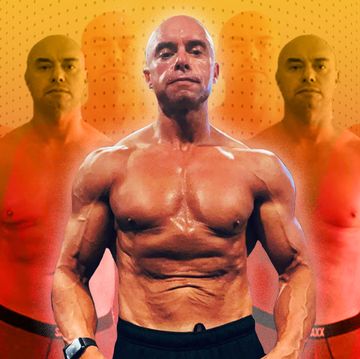

Eric Mair, M.D., a clinical professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is one of a growing chorus of scientists who argue that routine apnea screening needs to include a group rarely suspected as apnea candidates: strong, aerobically fit men, who are at heightened risk because of their muscularity.

In a 2006 study, Dr. Mair and researchers at the Wilford Hall U.S. Air Force Medical Center in San Antonio analyzed the relationship between apnea and aerobic fitness among members of the U.S. Air Force.

Over the years, the Air Force has performed 1.4 million tests of personnel, using stationary bikes to determine their VO2 max. "What we thought we'd see is that guys with apnea would literally flunk the VO2 max test," says Dr. Mair. "However, that wasn't necessarily true."

Many subjects with apnea, especially younger ones, actually proved to be fitter than their age-matched but apnea-free peers. The reasons for this paradox remain unclear, but Dr. Mair strongly suspects that weightlifting and other rigorous physical training may have a surprising downside.

"The traits that make professional soldiers formidable on the battlefield," he says, "including increased BMI from upper-body muscular hypertrophy, and large, muscular necks, can leave them gasping for breath as they sleep."

Dr. Mair's study, to be sure, is not the only research linking a muscular physique with sleep apnea.

In 2003, a headline-grabbing study published in the New England Journal of Medicine estimated that 14 percent of NFL players, including 34 percent of players at high risk for sleep-disordered breathing, have the condition. Sleep apnea was a factor in the death of Hall of Famer Reggie White, who died in his sleep a week after turning 43.

But even athletes who are less musclebound may face risks of their own. Helene Emsellem, M.D., director of the Center for Sleep and Wake Disorders in Chevy Chase, Maryland, has diagnosed sleep apnea in top distance runners and tennis pros alike.

"Age, obesity, deconditioning: These are what most people associate with apnea," she says. "But the reality of it is, the physical characteristics associated with optimal performance in certain sports can also predispose athletes to sleep apnea."

In the journal Clinics in Sports Medicine, Dr. Emsellem suggests, paradoxically, that even a thin neck can be a risk factor for sleep apnea.

Thin necks are common among men who engage in sports that reward low body weight, such as distance running. How? While the muscles and fat pads in a thick neck can encroach on a person's windpipe from the sides, a thin neck is narrow to begin with and may offer less room when the person's airway relaxes during sleep.

Another clue that Dr. Emsellem says should be on the diagnostic radar screen: a recessed jaw. When a man has retrognathia, as the condition is called, his tongue shifts back in his mouth. This change in the normal anatomy of his airway can impede airflow when the man lies down.

Or it can be a combination of these anatomic anomalies. "Anything that can go wrong in the airway will go wrong in some people," says veteran sleep researcher Michael Bonnet, Ph.D., chief of the Dayton V.A. medical center sleep lab.

Last night I again checked into the sleep lab, this time to see if CPAP, or continuous positive airway pressure, might reduce or even eliminate the 27.7 suffocation episodes per hour I averaged during my first visit.

The basic concept is straightforward: Blow pressurized air through my airway to keep it from flopping shut while I sleep.

Dara offered me a choice of two air masks: a full-face version that would cover both my nose and mouth, or a smaller, triangular one meant to cover only my nose. Most patients, she explained, are nose breathers during sleep, but a few also use their mouths because of septal deformities, sinus problems, or other reasons.

I opted for the smaller footprint: the nose-only approach. Dara seated the triangle so it fit comfortably and was tight enough to prevent air leaks, and secured it in place with straps around my forehead and jowls.

She then connected a flexible plastic air tube from the mask to the CPAP machine on the nightstand. The unit was surprisingly compact, not much bigger than a clock radio.

It could be programmed, Dara said, to pump room air at pressures ranging from 4 to 20 centimeters of water. During tonight's "titration" session, she would start low and slowly crank up the pressure necessary to keep my airway from collapsing.

With everything in place, I felt a bit like Gulliver tied down on Lilliput. Still, breathing through the mask was hardly the ordeal I'd dreaded, and I quickly fell asleep.

"Unfortunately," says Dr. Emsell em, "there's a huge iceberg effect with people who don't have any visual clue to the fact that their airway is collapsing during sleep. Sometimes I worry about apnea 'prototypes' because so many patients fail to fit any profile and in fact may be the diametrical opposite of what we're saying to look for."

The result for more than a few atypical sufferers is that it can take years before their sleep apnea is accurately diagnosed, if it happens at all. Regardless of external appearance, one often-overlooked symptom in men is a subpar sex life.

A 2009 study in the Journal of Sexual Medicine confirmed what urologists and sleep specialists had suspected for decades: Untreated sleep apnea is an independent cause of erectile dysfunction.

After factoring out other known causes of sexual problems, the researchers showed that men with apnea symptoms were 63 percent more likely to suffer problems in the bedroom than those without the condition.

(Getting more sleep is just one of 8 Ways to Protect Your Erection.)

Urologist Irwin Goldstein, M.D., editor-in-chief of the Journal of Sexual Medicine, believes apnea can damage penile tissues by depriving them of oxygen.

Healthy men, Dr. Goldstein says, sport nocturnal erections for 3 out of every 8 hours they sleep. During REM (or dream) sleep, an ancient part of the mammalian brain hardwired to sexual function triggers blood engorgement of penile tissues. The purpose of nocturnal erections, Dr. Goldstein believes, is not erotic but physiological.

Enhanced blood-flow brings an influx of oxygen that doesn't occur when the penis is in its flaccid state.

For many men, however, sleep apnea sabotages their sex lives in a much simpler, more straightforward way: by making them simply too exhausted to perform.

Tom Jaeger, M.D., an internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, once suspected sleep apnea affected a fit ad exec based solely on the man's twin complaints of lethargy and a lackluster libido.

"Sure enough," says Dr. Jaeger, "he had it. With treatment, the man's energy and sex life rebounded. How much of this effect was in his cortex and how much was in his crotch, I don't know."

"I've had patients who were so sleepy from apnea that they have literally fallen asleep in boiling-hot soup, or while driving a 40-ton rig, or in the middle of sex—you name it," says Mark Dyken, M.D., director of the sleep disorders center at the University of Iowa. "It's really hard to function well in any way when you're pathologically sleepy."

And yet even though chronic tiredness is probably the one universal symptom shared by almost all sleep apnea sufferers, some doctors will still ignore the obvious.

A common "misdiagnostic loop," explains Dr. Emsellem, begins when a lean man complains to his doctor about fatigue. In the absence of loud snoring, the doctor's first thought is likely to be depression, so he sends the man to a psychiatrist, who spends several months prescribing different antidepressants.

When these fail to help, the psychiatrist begins suspecting a "medical diagnosis"—an underactive thyroid, say—and sends the patient back to the internist for more futile testing before an underlying sleep disorder is considered.

"An atypical apnea patient can sometimes be shunted down such wrong pathways for years before his real problem is identified," says Dr. Winter, who is also the Men's Health sleep medicine advisor.

That's assuming, of course, that the guy even concedes that he has a problem. "It's very easy for men to come up with excuses for why they are feeling so sleepy," says Dr. Winter. "They'll tell you, 'I get up at 5:30 a.m. to run, I work all day, I exercise some more afterward. No wonder I feel tired.' "

I know firsthand the seductiveness of excuses. For years I blamed my own need for excessive sleep on a mix of overtraining in the pool and a cognitively demanding job. Nine hours in bed each night, another couple of hours napping on the couch: Sleeping half my life, I told myself, is the price dynamos like me must pay for our dynamism.

An onboard computer in the CPAP unit revealed that the number of times I stopped breathing while asleep dropped to normal after the first night's use. The machine clearly worked as designed—so why did I feel more pathologically groggy than ever?

When I asked a few experts what was going on, their counsel was unanimous: Give it time.

"There are a few patients who wear the thing for couple of nights, and the clouds part and the angels sing," says Dr. Winter, summing up the consensus sentiment. "But for most patients, it's a more gradual process. In your case, you've been sleep-deprived for a very long time. It will take some time to catch up. I predict that after a month you'll wake up and think, 'You know what? I do feel a little better than before.' Then another month will pass by, and you'll realize you're feeling even better still."

I'm dubious at first, but ever so gradually, his prophecy comes true. After 2 months of CPAP, I can't remember a time in my adulthood when I slept more soundly. The once-irresistible need to nap at least once and often twice a day has been replaced by a rare impulse to nod off briefly for old times' sake. I usually don't succumb.

As improved as my life feels, I don't want to overhype my progress.

"Not even CPAP can make us 20 again," says Dr. Bonnet in a much-needed therapeutic readjustment of my expectations. My libido, I freely acknowledge, is now more like that of a 35-year-old.

As for other, harder-to-see physiological benefits, from reduced stress loads on my right ventricle to normalization of my sleep architecture, I am taking on faith that these are occurring as well. Some things may be hard to prove but nevertheless still true, like the demise of a bogeyman who once wandered my dreamlands with his garrote.

Freddy's dead. And thanks to CPAP, he'll have no chance to rise again for a sequel.

(The National Sleep Foundation has updated its guidelines on how many hours of sleep people need. Find out the New Rules for the Best Amount of Sleep at Any Age.)

Five Fixes for Sleep Apnea

Try these and you may not have to strap on the CPAP every night

1 Stay off your back

Does your sleep apnea improve when you're snoozing on your side? Mark Dyken, M.D., director of the sleep disorders center at the University of Iowa, suggests this old trick for preventing snorers from rolling onto their backs: Fill a tube sock with tennis balls and sew it onto the back of a relatively tight-fitting T-shirt. Or buy a "bumper belt" ($85, antisnoreshirt.com/product_p/bb neoprene men.htm).

2 Play the didgeridoo

When sleep apnea sufferers blew through this aboriginal musical instrument every day for 4 months, they snored less and had 23 percent less daytime sleepiness than those who didn't play a note, Swiss researchers found. It may be that the repeated action of blowing into the didgeridoo tones your throat muscles, reducing the odds that they'll sag during sleep. Pick one up at laoutback.com for $120.

3 Exercise your airway

If you can't see yourself tooting a didgeridoo, try throat-toning exercises. Last year, Brazilian researchers found that people who performed a daily 30-minute set of vocal calisthenics, including reciting vowels quickly and continuously, experienced a 39 percent reduction in the severity of their sleep apnea. Go to MensHealth.com/apnea for your airway workout.

4 Wear a mouthpiece

Consider yourself "lucky" if your sleep apnea is caused by retro-gnathia, a.k.a. recessed jaw: The fix might be as simple as wearing a special mouthpiece to bed. These devices are designed to shift your jaw forward and prevent your tongue from falling back in your throat as you sleep. Talk to your dentist, ENT doctor, or a sleep medicine specialist about coming in for a custom fitting.

5 Clear your throat

There are surgical solutions to sleep apnea, such as uvulopalato-plasty, which involves removing sagging throat tissue. However, these procedures work half the time at best, and can occasionally make the situation worse. "Try everything else before considering surgery," says W. Christopher Winter, M.D., the Men's Health sleep medicine advisor. "Then seek at least two opinions."

How to Choose a Sleep Lab

Men's Health sleep medicine advisor W. Christopher Winter, M.D., reveals the questions you should ask—and the answers you should hear.

1 Is the lab accredited?

Go to sleepcenters.org to find a lab that's accredited by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. This is your guarantee that the director is a board-certified sleep physician and that the testing staff has specialized training in polysomno-graphic technology.

2 Who can they call on?

The best sleep centers can tap the expertise of neurologists, pulmonologists, psychiatrists, and other medical experts to diagnose different causes of sleep disorders. If these specialists aren't on staff, they should at least be on the director's speed dial.

3 What's the comfort level?

You'll be sleeping in a strange place, so it's critical that you feel as comfortable as possible. This means choosing a lab that has hotel-like bedrooms and test equipment that makes it relatively easy to move around, use the bathroom, and sleep in different positions—not just on your back.

4 What are the hours?

If you're a night owl or shift worker, you may not be able to sleep "on demand"—a potential problem at some smaller labs that conduct their studies only from 10 p.m. to 5 a.m. Choose a facility that offers a wide window for testing.

5 Can they fit your face?

If you're diagnosed with sleep apnea, the director will want to do a CPAP "titration"—a test to determine the minimum air pressure necessary to keep your airway open. Make sure the lab has access to a wide variety of mask types and sizes to accommodate your needs and preferences.