Abraham Lincoln's Secret Visits to Slaves

In the mid-1930s, the Federal Writers’ Project interviewed thousands of former slaves, some of whom claimed the president came to their plantations disguised as a beggar or a peddler, telling them they’d soon be free.

Shortly before the election of 1860, a man came upon a plantation near Marlin, Texas, some 20 miles southeast of Waco. Though nobody knew who he was, the plantation owner took him in as a guest. The stranger paid close attention to how the enslaved people working on the plantation were treated—how they subsisted on a weekly ration of “four pounds of meat and a peck of meal,” how they were whipped and sometimes sold, resulting in the tearing apart of families. Eventually, the stranger said goodbye and went on his way, but a little while later he wrote a letter to the plantation owner, informing him he would soon have to free his slaves—“that everybody was going to have to, that the North was going to see to it.” The stranger told the owner to go into the room where he’d slept, and see where he’d carved his name into the headrest. And when the slaveholder went and looked, he saw the name: “A. Lincoln.”

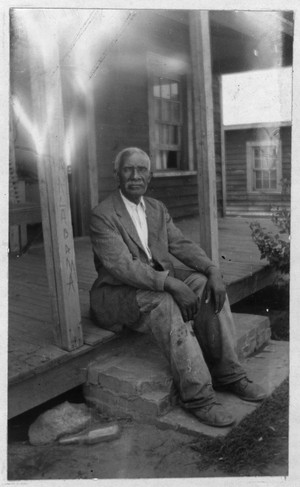

At least that’s what happened according to Bob Maynard, who was born a slave and recounted the story as an old man in an interview with an employee of the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), a New Deal program created to put writers to work and enrich American culture. In 1936, the FWP began collecting interviews with former slaves, amassing thousands of pages of oral histories which, though often filtered through the racism of white interviewers and their supervisors, provide an invaluable snapshot of how more than 2,000 survivors of slavery lived and thought.

Nearly 40 of those interviewed claimed Abraham Lincoln visited their plantation shortly before or during the Civil War. They said he came in disguise as a beggar or a peddler, bummed free meals off his unsuspecting white hosts, snooped around to find out what slavery was like, and told the slaves they would soon be free.

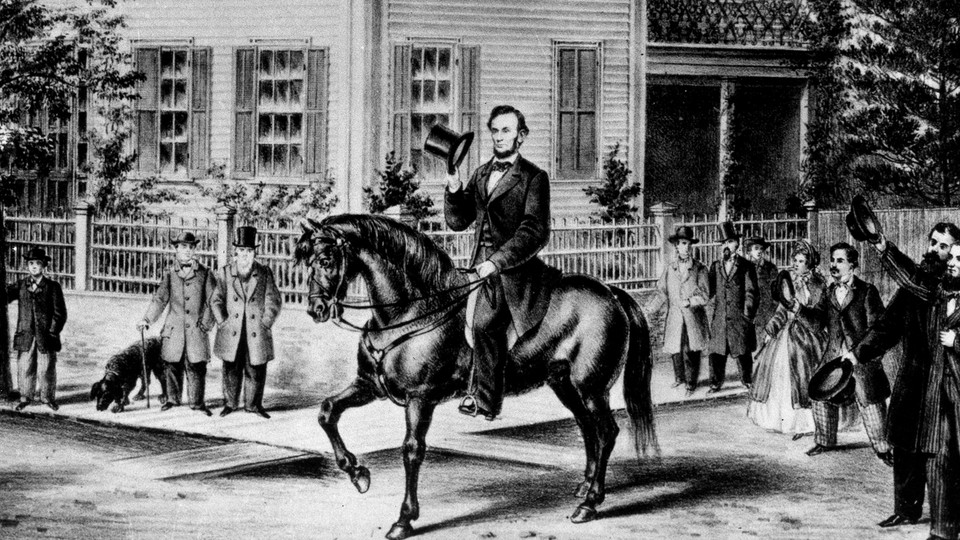

Virginia Newman claimed Lincoln came through Jasper County, Texas, in a large carriage. He shook Newman's hand and called on the white population to free their slaves. “Some folks say dat ain’ Abr’am Lincoln,” remarked Newman, “but I knowed better.” / Library of Congress

The stories weren’t limited to one corner of the South. Lincoln didn’t just visit central Texas; he also visited the Mississippi Delta, the Kentucky Pennyroyal, and the Georgia Piedmont. In fact, as late as the 1980s, African Americans in the South Carolina Sea Islands claimed that Lincoln traveled there in 1863 to announce the Emancipation Proclamation in person; some even said they knew the exact tree under which he stood.

Though there’s no evidence Lincoln actually made any of these incognito visits to the South—and ample documentation to suggest these visits were wholly fictitious—it’s important that many former slaves believed he did. Today, historical debates over emancipation often focus on whether it came from the top down or the bottom up—did Lincoln free the slaves, or did the slaves free themselves? But the stories of Lincoln coming down South suggest many freedpeople didn’t see this as an either/or question.

Did they need Lincoln? Sure. But emancipation wasn’t something Lincoln could just decree from on high. He had to come down South and get his hands dirty. Some even described him as taking on the guise of the trickster popular in black folklore, a sort of Brer Rabbit in a top hat. When former slaves claimed Lincoln had paid them a visit, they weren’t just inserting a beloved president into their story—they were inserting themselves into his story.

African Americans were understandably wary of associating Lincoln too closely with their emancipation. Doing so, after all, implied freedom was a gift from a benevolent white man that could be easily taken away. Indeed, the former slave Charity Austin recounted that, when Lincoln was assassinated, her owner said Lincoln’s death meant they were slaves again, and he kept the ruse up for a year, making them work in black mourning cloth. In 1908, some 30 years before the Federal Writers’ Project began interviewing former slaves, a white mob in Springfield, Illinois, enraged by recent crimes allegedly committed by African Americans, lynched two black men and burned down black homes and black-owned businesses, finally driving roughly 2,000 African Americans out of Lincoln’s hometown. The mob shouted: “Lincoln freed you, we’ll show you where you belong.”

African Americans were not foolish enough to think their welfare would be the utmost concern of a white politician. As Frederick Douglass said, Lincoln “was preeminently the white man’s President,” and they were “at best only his step-children.” But this didn’t mean Lincoln couldn’t be a useful ally, especially if his own self-interest aligned with theirs.

In the stories of Lincoln coming down South, he was rarely concerned first and foremost with the welfare of black people. In one story, for example, his animosity toward the slaveholding class was seemingly motivated by a perceived insult rather than a moral opposition to slavery. Lincoln had supposedly visited a plantation in Jefferson County, Arkansas, asking for work. The owner replied that he’d talk to him once he’d had dinner—without inviting the stranger to eat with him. As J. T. Tims, a former slave, explained, his owner “didn’t say, ‘Come to dinner,’ and didn’t say nothin’ ’bout, ‘Have dinner.’ Just said, ‘Wait till I go eat my dinner.’” And when he finished eating, he found the stranger had “changed his clothes and everything” and was looking over the slaveholder’s business papers and account books. The stranger whom the slaveholder had treated like poor “white trash” had revealed himself to be a powerful man.

It didn’t bother African Americans if Lincoln emancipated them only to punish the white South. They didn’t need him to be a saint. But they also knew he wasn’t a king; he couldn’t just make emancipation happen on his own. If the enslaved people of the South needed Lincoln, then he needed them too.

And so in the stories told by freedpeople, there’s a Lincoln who worked with slaves to end slavery. He attended nightly prayer meetings held by slaves in secret. He asked them what their lives were like and what they needed from him. After the war broke out, he encouraged slaves to join the “Yankee army” and “fight for your freedom.” And at the war’s end, according to one account, Lincoln gathered up all the Confederate money in Georgia in a big pile at the state capitol and asked the oldest black man there to set it on fire.

Lincoln didn’t just work with African Americans; he became a familiar figure in black folklore. Like Brer Rabbit, and indeed like most slaves, the Lincoln in these stories often had to resort to guile and deception in order to get what he wanted. But he also had a certain degree of latitude that wasn’t possible in slavery, allowing survivors of slavery to vicariously enjoy his exploits.

In one account, for example, Lincoln, disguised as a peddler, came upon some white women sitting on a porch in North Carolina. He looked so hot and tired that one of the women, Miss Fanny, brought him a “cool drink of milk.” He had a drink and then asked Miss Fanny how many slaves they had, how many of their men were fighting for the Confederacy, and finally what they thought of “Mistah Abraham Lincoln.” At that point the plantation mistress, Miss Virginia, declared no one was to speak that man’s name in her presence, and she would shoot him if he ever set foot on her property. “Maybe he ain’ so bad,” her guest said, chuckling. A few weeks later, Miss Fanny received a letter from Lincoln revealing himself to have been the peddler, thanking her “for de res’ on her shady po’ch and de cool glass of milk.”

Though the story didn’t explicitly involve emancipation, by making a fool out of white slaveholders Lincoln presaged the ultimate downfall of the southern slaveocracy. But that wasn’t all. By behaving like a trickster from black folklore, Lincoln was signaling—or rather, black storytellers were signaling—his solidarity with African Americans.

To that end, Lincoln also often duped his white hosts into giving him food. In Perry, Georgia, he enjoyed some “chicken hash and batter cakes and dried venison.” In Raleigh, North Carolina, he had a rather enormous breakfast of ham and gravy, biscuits and grits, “poached eggs on toast, coffee and tea,” and waffles with “honey and maple syrup.” Food was often a focus for black trickster characters like John, Brer Rabbit, and Aunt Nancy; after all, slaves frequently had to cheat and steal from their enslavers in order to get enough food to survive. It was fitting, therefore, that when Lincoln returned to Perry, Georgia, to emancipate the slaves, he did so by allegedly urging them to raid the plantation smokehouse: “Help yourselves; take what you need; cook yourselves a good meal!” In the stories told by former slaves, emancipation wasn’t just an abstract matter of rights—it meant seizing, at long last, the product of their labor.

Of course, these stories about Lincoln were told within a specific historical context. The people interviewing the former slaves were employees of the federal government, and most of them were white. Many were members of groups like the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which valorized the Lost Cause. Some were even descendants of folks who owned the very people they were interviewing. Survivors of slavery had every reason to believe their white interviewers would present their stories in a way that bolstered white supremacy. And telling a quaint story about Abraham Lincoln was a clever (and relatively safe) way to push back against that.

Using Lincoln was especially powerful at a time when many Americans had co-opted Lincoln as an icon of white supremacy. The 1915 blockbuster film The Birth of a Nation, in addition to denouncing emancipation and venerating the Klan, depicted Lincoln as an enemy of the radical abolitionists and suggested that, had he lived, he would have supported immediate reunion with the South at the expense of black civil rights.

In general, white Americans celebrated Lincoln in a way that made the Civil War a story about white people. They spoke of Lincoln in the same breath as Robert E. Lee, considering them both American heroes. There was a popular story that Lincoln had comforted a dying Confederate prisoner who didn’t know who he was, and that when Lincoln derided his recent address at Gettysburg, the dying rebel assured him they were “beautiful, broad words” which reminded everyone they were “not Northern or Southern, but American.”

Such a sentimental reunion of North and South was, of course, a primarily white affair. And when African Americans were included in Lincoln’s story, it was only in a subservient role.

This was not how survivors of slavery understood their relationship to Lincoln. He wasn’t far-off and aloof; he worked hand-in-hand with black folk. He listened to the slaves’ stories. He made fools out of slaveholders and urged black people to fight. As Charlie Davenport remembered, Lincoln came through Mississippi “rantin’ an’ a-preachin’ ’bout us bein’ his black brothers.”

Perhaps they weren’t related by blood—perhaps he was only a stepfather. But they were still kin. At a time when many Americans were remaking Lincoln into a symbol of white supremacy and erasing black people from the story of the Civil War altogether, survivors of slavery were saying, through their stories of Lincoln coming down South, that they could not be erased. They wouldn’t be forgotten. They’d been there the whole time.