The health secretary, Jeremy Hunt, has apologised on behalf of the NHS and government for 20 years of “anguish and pain”, following the publication of a major report which found that more than 450 elderly people were given life-shortening opioid drugs they did not need.

The families of those who died at the Gosport War Memorial hospital in the 1990s said they had finally been believed after two decades of campaigning, but pledged to continue to fight for criminal prosecutions not only for the doctor who prescribed the drugs but also others who knew and failed to stop the practice.

“This is the beginning of another journey,” said Ann Reeves, whose mother Elsie Devine, 88, was one of those who died. “It was quite a shock – for the first time somebody telling me what I knew 18 years ago. I want the people responsible for the deaths of our loved ones. We want them back in the criminal court. That’s the way it should go.”

Speaking in the House of Commons, Hunt said the police, working with the Crown Prosecution Service and clinicians, would consider whether criminal charges should be brought and suggested that Hampshire constabulary should consider whether the investigation should be conducted by another force given its “vested interest”.

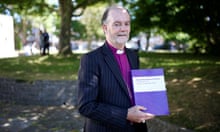

The report, led by the former bishop of Liverpool James Jones, who ran the Hillsborough inquiry, said the home secretary, attorney general and Hampshire police should all “recognise the significance” of the review findings. It looked at 1,500 deaths at the hospital and found that 456 followed inappropriate administration of opioid drugs and a possible 200 more patients had their lives shortened.

“Nothing I say today will lessen the anguish and pain of families who have campaigned for 20 years after the loss of a loved one, but I can at least on behalf of the government and NHS apologise for what happened and what they have been through,” Hunt said.

He recognised the harrowing years relatives had spent trying to find answers and having doors shut in their face, which included the refusal of the Department of Health to publish a report in 2003 that concluded there had been routine over-prescribing of opioids in Gosport with life-shortening effects.

The independent report found that Dr Jane Barton, a GP working as a clinical assistant at the hospital, routinely overprescribed drugs for her patients in the 1990s. Consultants were aware of her actions but did not intervene. Nurses and pharmacists collaborated in administering high levels of drugs they would have known were not always appropriate.

Some senior nurses in 1991 tried to raise the alarm over using diamorphine – the medical name for heroin – for patients who were not in pain, administered through a syringe-driver pumping out doses that were not adjusted to each patient’s needs.

A staff meeting was held that was attended by a convenor from the Royal College of Nursing. But the nurses were warned not to take their concerns further. They had, the report said, given the hospital the opportunity to rectify the overprescribing.

“In choosing not to do so, the opportunity was lost, deaths resulted and 22 years later, it became necessary to establish this panel in order to discover the truth of what happened.”

Jones said apportioning blame and the issue of criminal prosecutions was not within the remit of the panel. He described what happened as an “institutional practice” and spoke of the deep distress to the families.

“Handing over a loved one to a hospital, to doctors and nurses, is an act of trust and you take for granted that they will always do that which is best for the one you love,” Jones said in the introduction to the report.

“It represents a major crisis when you begin to doubt that the treatment they are being given is in their best interests. It further shatters your confidence when you summon up the courage to complain and then sense that you are being treated as some sort of ‘troublemaker’.”

“It is a lonely place, seeking answers to questions that others wish you were not asking.”

The patients and their families – who the report said had shown “remarkable tenacity and fortitude in questioning what happened to their loved ones” – were failed by numerous inquiries and investigations over many years. The report criticised healthcare organisations, the limited police investigations and the processes of the General Medical Council.

In 2009, Barton appeared before a disciplinary tribunal of the GMC, the doctors’ regulatory body, where she was heavily censured and conditions placed on her practice. The GMC later said it was wrong not to strike her from the medical register.

In a statement, Jones said: “Families will ask: how could this practice continue and not be stopped through the various police, regulatory and inquest processes? The panel’s report shows how those processes of scrutiny unfolded and how the families were failed.”

Diamorphine was the main life-shortening opioid drug given to patients, often in a syringe-driver, which was attached to the patient’s back and ensured a constant dosage. The report recounted the testimony of Pauline Spilka, a nurse who gave evidence to the Hampshire police in 2001 during their inquiries. She said she had never heard of a syringe-driver before she worked at Gosport.

She later learned it was used to give drugs to seriously ill patients. “It was also clear to me that any patient put on to a syringe-driver would die shortly after,” Spilka told police at the time. “During the whole time I worked there I do not recall a single instance of a patient not dying having been put into a driver.”

She was deeply troubled, she said, by the case of one man aged about 80 who had stomach cancer but was lively and able to wash and look after himself. “One day I left work after my shift and he was his normal self. Upon returning to work the following day I was shocked to find him on a syringe-driver and unconscious.” He was unconscious until he died, she said. She felt unable to speak to his family, convinced the death had been unnecessary.

Opioid drugs are used to relieve severe pain. The medical notes were poor but in 456 cases there was no evidence the opioids were justified.

The report spoke of “anticipatory prescribing”, which can be used to ensure patients get pain relief when they need it. But in Gosport, records show anticipatory prescribing “in a very wide dose range” with no specified trigger for the start or the end of it.

“In some, prescribing was done on the day of admission of patients not admitted for end-of-life care,” said the report. This was contrary to guidance at the time.