Thanks to this newspaper’s belief in self-improvement and its need in these hard times to earn a bob or two, a reader can sign up to a Guardian Masterclass and learn how to be a columnist. Not only a columnist, of course: there are many other skills you can learn. Column writing, nonetheless, is the course to which I’m strangely drawn.

I’m genuinely interested to know how it’s done. I imagine wearing a mask to disguise my identity and picking up advice on how to make the column better, or at least easier to achieve. “The art of applying the ass to the seat,” is how Dorothy Parker described writing in general, and that’s more or less all I know about the practice of writing a column. I’m not suggesting for a moment that that’s all there is to know, or that what’s knowable can’t be taught. A large cultural industry in the shape of university creative writing schools has been built around the proposition that writing, particularly “literary” fiction, is a skill that can be transmitted by tuition.

We have to recognise the fact that many more people could write novels and columns than do write novels and columns – ambition, application, social connection and luck have as much to do with success as a “gifted imagination” or “natural talent”. The question more concerns consumption than production. Are there enough people who don’t read novels and columns, or can’t get enough of them, who would read them, or more of them, if they could?

At one time, in the great age of popular printed literature, the answer would have been yes. “The art of writing for publication is one of the greatest creative forces in modern life,” says the foreword to a booklet (Modern Journalism & Story Writing: the Ambitious Writer’s Guide to Success) that a friend gave me recently, having inscribed on the title page the words “Never too late to learn”. It was published by the Metropolitan College of Journalism – with an address in the metropolis of St Albans – and its sepia pictures and typographical get-up suggest a date in the 1920s. Two considerable journalists of that time, Beverley Nichols and James Drawbell, are listed as the chief editors of the courses on offer – which arrived through the post in up to 25 instalments, each with exercises that the student returned to be evaluated by his or her tutor.

Like other institutions that grew up in the social desperation that followed the first world war – years in which factories shut their doors for ever and maimed ex-soldiers sold shoelaces – the Metropolitan College sounds just a little bogus. Its courses “represent the pure gold of knowledge crushed from the crude ore of experience”. Its students are promised that an “almost insatiable demand” exists for the work of the freelance journalist, and a world in which “innumerable editors must constantly find fresh copy to sustain their papers against the fierce and relentless competition of their rivals”, where “give me copy I can use!” is the editorial cry.

Usable copy is what the college promises to teach, literary technique not being “a difficult matter, for even people with a comparatively poor education … master its intricacies with ease, and discover that they can be taught to write by a skilled instructor as easily and naturally as they learned to talk at their mother’s knee”. As for profit (“for who, nowadays, can afford to ignore the appeal of the purse?”), the sky was the limit. Freelance journalism offered “a chance without parallel in any other career” to win fame and prosperity. The student would be taught what to write, how to write, and where to sell his manuscript. A complete course cost 12 guineas.

How many people became journalists and writers by this method is impossible to know. Perhaps not many: no journalist’s memoir so far as I recall has a correspondence course as its career starting-point. By contrast, many begin humbly on local newspapers. James Cameron, who wrote one of the best memoirs, recalled that his first job was to fill the paste pots every day in the Manchester offices of the Weekly News. I do not remember reading a scene in which a student sits down in the evening to write 750 words at the kitchen table on a subject chosen by their distant tutor – “Naval and Military” and “Personal and Gossip” were among the 1,200 categories on the Metropolitan College’s subject list.

And yet teach-yourself-to-write postal courses persisted late into the last century, and made at least enough money to afford adverts on broadsheet front pages, the so-called “solus position” at the bottom right that was also favoured by remedies for hair loss and the need to start your pension aged 25.

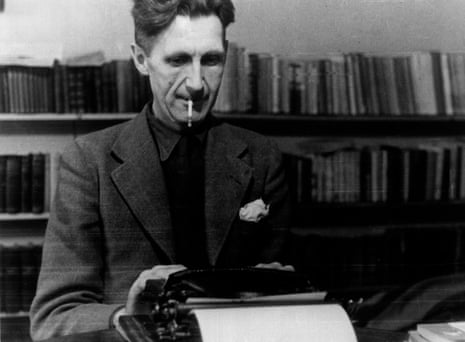

The one lasting legacy of these courses, or at least of the instinct for literary self-improvement that produced them, is the writing manual. Two new titles in the genre have just been published: How to Write Well by Tim de Lisle, and Do I Make Myself Clear? by Harold Evans. I’ve been a colleague of both (to declare my interest) and I know them to be fine journalists – Evans famously so. Each book has its merits. De Lisle’s is brisker, briefer and cheaper than Evans’s, which is more philosophical and more morally outraged by opacity, obscurity and the political language that George Orwell – who has become the patron saint of such manuals – said is “designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind”.

The virtues most praised are clarity and concision. Evans bravely takes on a sentence from Pride and Prejudice that seems to be wandering around a darkened house looking for a way out, and makes a far better job of it than Jane Austen did. De Lisle warns us that brevity – a necessity imposed by the limitations of hot metal and newsprint – has its drawbacks when reborn as a fashion by Twitter or in emails. Padding (“Hope you’re well”) does have its uses.

Language is frequently debased, corrupted and made incomprehensible by academia, governments and big business. The insurance company Aviva and its architect partners recently unveiled a bronze plaque at a new office development in Mayfair that reads: “Hanover Square exemplifies a 21st-century idea of London: it’s [sic] fascinating mix of historical and contemporary styles with a seamless tradition between business and culture, as well as the city and natural spaces.” How could such illiterate bunkum have been permitted by a global business staffed by thousands of university graduates and equipped with PR and marketing departments? In the age of mass literacy, the writing manual seems more necessary than ever.

Still, I read these books warily, not wishing to remember them too well. Their instructions can be inhibiting. Ration adjectives! Raze adverbs! Avoid the passive voice! In his book’s most fascinating section, Evans recounts the history of readability as a study, in which sentence analysts such as the American Rudolf Flesch (who is said to have inspired Dr Seuss) urged writers to average 18 words per sentence if they wanted the reader to have an easy understanding of their prose. For me, and I suspect for many others who do it for a living, writing is like riding a bicycle: its techniques are best not dwelt on. In the end, I am too scared of falling off to sign up for a masterclass.