My unhappy 48 hours as an astronaut

Neil Scheibelhut/Hi-Seas/University of Hawaii

Neil Scheibelhut/Hi-Seas/University of HawaiiVolunteers are trying to live like astronauts on Earth in preparation for manned missions to Mars, but face isolation, confinement and terrible food.

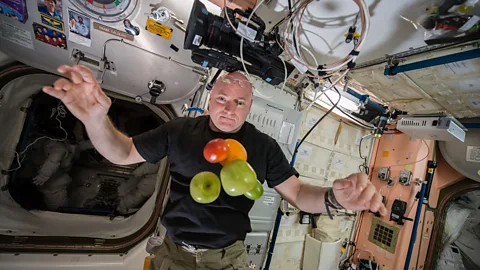

After almost a year without fresh air in the cramped, near-weightless environment of the International Space Station (ISS), American astronaut Scott Kelly and Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko seemed remarkably healthy when they touched down back on Earth last Spring. They had just completed a 340-day mission onboard in orbit, one of the longest space trips in recent years.

They rank among the more than 200 people who have had the fortune to visit the ISS, and hundreds more who have travelled to space. That’s not a lot in the scheme of things, but plenty of people all over the world are investing billions in the future of space travel in the hope that many more of us may one day follow in their footsteps.

Yet, it is not always necessary to travel into space to experience what it is like living as astronauts do. It may come as a surprise to discover on Earth, dozens of people all over the world have spent months, and even over a year, living in specially built confined spaces that mimic life in space. These simulation pods are found in places like China, Hawaii and Russia, giving researchers the ability to study the effects of long-term isolation and confinement on people in preparation for long-haul space travel.

While we can glean plenty of information from astronauts’ experiences in the ISS and its predecessors, the challenges faced by astronauts will change as space agencies set their sights on the Red Planet. A mission to Mars will mean spending approximately three years in space – six-to-eight months to travel there, several months on the surface, and six-to-eight months to return. The long-term nature of the trip is expected to pose several psychological challenges for those picked to make it.

Ross Lockwood

Ross LockwoodTo find out what it might be like, for 48 hours, I tried to live just as astronauts do – attempting to keep up with the schedule of crewmembers on the ISS. As it turns out, they have a very tightly packed workday. I woke up, drank coffee, ate not-so-great food directly from the bag, worked out, worked and repeated the pattern until the day was done. Oh, and I had to spit into a towel twice a day after brushing my teeth.

A typical day onboard the ISS begins by getting up at 6 or 6:30am (the ISS uses Coordinated Universal Time or GMT). American astronaut and medical doctor Kjell Lindgren spent 141 days aboard the ISS in 2015, participating in two space walks. He says he started his days reading a daily summary of the news and a two-page summary of the previous day, brushing his teeth and eating breakfast. By about 7:30am each crew has a daily planning conference with their respective mission controls to plan the day ahead and ask any questions.

“The rest of the day is very tight – it’s scheduled down to five-minute activities,” Lindgren explains. “Within that day we might do research, maintenance on the station, or take photos of natural disasters. We get an hour for lunch and two-and-a-half hours for exercise.”

SAMPLE DAILY LOG FOR ASTRONAUTS ON THE INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION

7am GMT Central – Wake up and don arm band to record ECG measurements for Bio Rhythms experiment

7:05am – PostSleep (time when the astronauts go through their morning hygiene routines, eat breakfast, etc)

8:30am – Morning Daily Planning Conference: time when the astronauts talk briefly with the various control centers around the world (Nasa, Roscosmos, JAXA, Esa, CSA) about the activities scheduled for the day

8:45am – Morning Prep

9am – install computer update

9:05am – exchange data collection cards on the Bio Rhythms hardware

9:25am – gather equipment for upcoming maintenance activity

10:25am – treadmill exercise

11:25am – Personal CO2 monitor data collection

12:15am – Window shutter close

12:25am – white space (downtime – they normally wouldn’t have much of this, but they worked over the weekend, so this gives them some of that time back)

1:10pm – Ethernet cable swap

1:15pm – Video camera set up (to record maintenance work for the ground)

1:25pm – Nutrition experiment questionnaire assessing food frequency

1:35pm – midday meal

2:35pm – white space

3:05pm – Ared exercise (advanced resistive exercise device – a microgravity version of weight lifting)

4:35pm – capture photos for the AMO2 experiment to be sent to the ground

4:40pm – install a vacuum access port in Node 1 to provide vacuum capability for visiting vehicles that will berth there

7pm – Configuration checkout for Materials Science Research Rack computer

7:20pm – Orbital-6 Cygnus vehicle cargo inventory

7:35pm – weekly astronaut office/crew conference

7:55pm – PreSleep (time for evening activities, such as dinner, etc.)

8:25pm – weekly flight director/crew conference

8:45pm – Evening Daily Planning Conference (time for the astronauts to talk with the ground team about work accomplished during the day and plans for tomorrow)

9pm – PreSleep time resumes

10:30pm – Sleep

* Source Nasa – sample log for astronaut Tim Kopra

At 7 or 7:30pm each crew has an evening conference to summarise the day. “After that the day belongs to us,” says Lindgren. “We’ll have dinner, we might watch a TV show together, answer emails, take photos of Earth. Then it’s time to get ready for bed by 10 or 11 to prepare for the next day.” During his mission, Lindgren and the rest of the crew were lucky enough to enjoy a preview Ridley Scott’s film The Martian before it was released on Earth.

During my astronaut day, I kept busy by interviewing researchers, reading academic papers, taking notes for this story and watching recent videos made on the ISS. One of the hardest and best parts of course was exercising at least two hours a day (I split it into two one-hour workouts of interval cardio training, weightlifting and yoga.)

Of course, astronauts have to exercise at least two hours a day to counter the physical effects of being in microgravity, which has been shown to decrease bone density, muscle mass and cardiovascular conditioning. And exercising in microgravity has to be creative – astronauts can strap themselves into an exercise bike that has resistance, or in some cases rig up their own resistance machines for “lifting” weights.

“We’ve developed a pretty good system of countermeasures to counter the effects of weightlessness so we maintain our aerobic capacity, bone density and muscle strength,” says Lindgren. “But it’s not a pure remedy for lack of gravity. There are some muscles that just aren’t able to respond. Just by standing up you’re using small postural muscles in your spine that you don’t exercise in the same way by doing squats or dead lifts.”

Canadian Space Agency, Nasa

Canadian Space Agency, NasaJapanese astronaut Naoko Yamazaki, who spent 15 days on an assembly and supply mission to the ISS in 2010, says she was amazed by the heaviness of gravity upon her return to Earth. “I remember that my head felt so heavy, as if I had a stone on it. Even a piece of paper felt very heavy to hold,” she says. Though Yamazaki was able to walk about an hour after returning to Earth, those who spend longer in microgravity usually need weeks and sometimes months to adjust to the gravity of Earth.

In recent years, researchers have turned their attention to how microgravity can cause astronauts to lose visual acuity. “Crew members are coming home and recognise that they’ve had some vision changes,” says Lindgren. “There’s a significant issue here but we don’t understand the causes yet.”

Since microgravity causes bodily fluids to shift upwards, experts suspect that increased pressure around the eyes might affect vision. The fluid shift might even cause changes in taste.

Space food

For me, the food was one of the most difficult parts of my at-home confinement.

There are three types of food on the ISS – packets of cooked wet food that are heated up, dehydrated food that is rehydrated with hot water, and shelf-stable items that are vacuum packed for stability and eaten as they are. Astronauts are also successfully growing plants in microgravity, but the ability to grow large-scale crops in space is probably still far off.

Nasa Johnson

Nasa JohnsonSince I wasn’t able to get my hands on real space food, I went to my local outdoor shop and stocked up on dehydrated meals. But choosing my meals in advance was surprisingly difficult. I didn’t know how to design a menu that would be satisfying for two days or predict what I would feel like eating. After the first day, I found myself fantasising about fresh produce. Imagine doing that for several months.

It turns out these are some of the biggest issues scientists are addressing as well. Experts are not only concerned with how to make sure there is enough food to last during a mission to Mars – one idea is to send cargo shipments before or after the manned flight arrives – but also how to increase the chances that astronauts will like what they’re eating.

“Preferences in terms of food becomes very important when you are confined,” says Gro Sandal, a professor of psychology at the University of Bergen who was a principal investigator in Mars500 – a 520-day Mars simulation conducted in Russia in collaboration with China and the European Space Agency. She says some crewmembers hated the food so much that researchers were concerned they would go on a hunger strike and had to intervene by introducing new options.

Bryan Caldwell, project manager at the Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation (Hi-Seas), says astronauts report their food preferences and tastes often change while they’re in space. Experts suspect the phenomenon is due to the way fluid in the body shifts in microgravity and examined the effects of those changes in a 70-day study, in which participants were reclined in beds to mimic weightlessness.

Tiffanie Wen

Tiffanie Wen“We want to know how the nasal congestion of weightlessness might affect smell and taste,” he says. “We are still working on the results, but it would seem that while the body fluid redistribution of bed rest doesn’t affect smell so much, it does have an effect on food liking.”

On the ISS, food has become a type of social currency and a way to bond with people of other cultures. “When you go up there, it’s a mixture of different cultures and nationalities,” says Yamazaki. “We have some joint training beforehand, but it helps that for dinner we get together and dine together every night. And we exchange space food, which helps us communicate with each other.”

Nasa Johnson

Nasa JohnsonWhich brings us to a piece of good news for travellers to Mars. Though there will likely be limited food options on the journeys to and from the Red Planet, people will be able to cook for themselves more normally once on the surface, and create recipes based on the shelf stable ingredients sent ahead of their arrival and during their stay. The group of participants from the eight-month Hi-Seas confinement study is even working on a cookbook detailing the creative recipes they came up with while in isolation.

Just another star in the sky

While crewmembers aboard the ISS have stunning views of Earth, virtually no delay in communications with their families and support teams on the ground, a constantly changing crew, together with regular shipments of supplies from Earth, astronauts who go to Mars will face far more extreme isolation.

On top of the far longer mission times, it will take around 20 minutes for communications with Earth to travel each way. This will mean a 40-minute delay before astronauts will get a response from mission control or anyone else back home. This lag time was simulated in the Hi-Seas missions as well as Mars500.

Jocelyn Dunn spent eight months as one of six crewmembers living in a dome as part of the Hi-Seas mission in Hawaii. The two-storey building had about 900 square feet of shared living space, with small personal quarters, and the experiment included simulated work on “Mars” in the surrounding lava fields. Participants donned space suits whenever they ventured outside and were responsible for conducting geological tasks in teams.

“For me personally, communication was unexpectedly difficult,” Dunn says. “Not just because of the time delay but also because it was only through email. We have become such a quick, text-oriented society and it was surprising that some people weren’t that good about keeping in touch. It’s especially hard because your social network has an impact on your identity.”

Furthermore, Earth will look like just another star in the sky from Mars. This could lead to something researchers have called the “Earth-out-of-view phenomenon” and will likely increase feelings of isolation. Surveys of astronauts have indicated how important the experience of appreciating the beauty and fragility of Earth from space is, with studies indicating the experience can make people value individualism less and things like universalism and spirituality more.

ESA/NASA

ESA/NASA“Seeing the Earth from that perspective is life-changing for everyone going up there,” Lindgren says. “You really have the opportunity to see that we are on an absolutely incredible planet that is unique to everything else that you can see. And though you can see the cosmos and that makes people feel small sometimes, you realise that there’s nothing in your vision and experience like the Earth.”

He says the experience made him realise that Earth is humanity’s space ship and human beings, its crew. “I spent 30% of my time maintaining the space station, the vehicle that provided us with oxygen and food and protection from radiation,” he explains. “And you look back on the Earth and think, that’s humanity’s space ship. The same goes for the crewmates and humanity – we’ve got to take care of each other.”

Not having those views may negatively affect space travelers’ experiences. When coupled with confinement, it could make things very stressful indeed.

The stress of confinement

For me, by day two, the novelty of being trapped in the house with dehydrated food had definitely worn off, and my husband came home to a particularly grumpy wife. As boring as my at-home experiment sounds, the monotony of confinement may actually one of the biggest challenges people face on a mission to Mars.

Dunn, who collected biological samples to track stress levels during her own stint with the Hi-Seas study, says she underestimated the effects of confinement in her own experience.

“People don’t think about the confinement as much,” she says. “They think about the isolation – you’re without all these things you normally have in the world, but confinement is just as hard, if not harder, because it is very intense socially. You can’t go away for the weekend, you can’t change the scene, the people. I really missed being able to walk down the street or do something spontaneous or discover something new.”

Nasa

NasaDunn since joined the research team as a principal investigator for the subsequent 12-month Hi-Seas study that concluded in August last year and is now analysing how the stress levels of participants changed over their time living in the dome. “People come in with decently high stress levels because they’re coming in for the first time and excited, but then it subsides as they adjust to the environment,” she says. “Then over time stress starts climbing again as they live in the environment, though exactly when and how depend on the individual.”

Increased stress might also contribute to more social conflict as astronaut live together for long periods of time. A 2010 analysis of astronauts’ journals by Nasa, for example, reported that they showed, on average, a 20% increase in interpersonal problems in the second half of their missions.

While not always the case, at least some researchers have observed something called the “third quarter phenomenon” – an increase in aggression and emotional outbursts at some point following the halfway point in a space mission.

In Mars500, which took place from July 2010 to November 2011 and is the longest space simulation study to date, researchers found that participants decreased their emphasis on benevolence as time went by, with some participants withdrawing from interaction with others. This was especially true between May and August, considered the “third quarter” since participants were scheduled to leave the chambers in November.

Pool/AFP/Getty Images

Pool/AFP/Getty Images“What we found was that when people are confined over a long period of time, certain times of the confinement seem to be more critical in terms of psychological functioning, especially if you are in a situation of very restricted stimuli,” says Sandal. “After a while you will become very easily irritable and any kind of sound or stimuli may feel too much. It will feel uncomfortable for you. And that’s something we observed in Mars500. There are individual differences of course, but some crewmembers withdrew from interaction a lot, which I interpreted as a way of protecting themselves.”

They also observed a psychological phenomenon called “disassociation” from some crewmembers, who would detach from their environment and go into an internal world. “So they kind of protect themselves and go into an inner world,” explains Sandal. “And we see that in isolation research from Antarctica too.”

Of course, there are personal differences in who does well in extreme circumstances, which is something Hi-Seas and other researchers are essentially trying to tease out. The selection parameters for long-term space missions will be critical, and training on Earth will likely take several years.

Despite the challenges though, space agencies are unlikely to have problems attracting applicants for the first missions to Mars. Even researchers conducting isolation studies on Earth get hundreds of applications from volunteers eager to get a taste of what a long mission in space might be like.

Non-government projects are also betting regular people will want to travel to Mars. Elon Musk’s SpaceX hopes to send tourists to the Red Planet, while the Dutch nonprofit MarsOne intends to establish a permanent colony of humans there.

As for me, at they end of my two days I walked out of the house with a new appreciation for fresh air and fresh food. I won’t be signing up to go to space anytime soon.

Join 800,000+ Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, Google+, LinkedIn and Instagram

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.