Her perspective has a lot of intuitive appeal in an era where millions of women have children outside of marriage, serve as breadwinner moms to their families, or are raising children on their own. Dads certainly seem dispensable in today's world.

What this view overlooks, however, is a growing body of research suggesting that men bring much more to the parenting enterprise than money, especially today, when many fathers are highly involved in the warp and woof of childrearing. As Yale psychiatrist Kyle Pruett put it in Salon: "fathers don't mother."

Pruett's argument is that fathers often engage their children in ways that differ from the ways in which mothers engage their children. Yes, there are exceptions, and, yes, parents also engage their children in ways that are not specifically gendered. But there are at least four ways, spelled out in my new book, Gender and Parenthood: Biological and Social Scientific Perspectives (co-edited with Kathleen Kovner Kline), that today's dads tend to make distinctive contributions to their children's lives:

The Power of Play: "In infants and toddlers, fathers' hallmark style of interaction is physical play that is characterized by arousal, excitement, and unpredictability," writes psychologist Ross Parke, who has conducted dozens of studies on fatherhood, including a study of 390 families that asked mothers and fathers to describe in detail how they played with their children. By contrast, mothers are "more modulated and less arousing" in their approach to play. From a Saturday morning spent roughhousing with a four-year-old son to a weekday afternoon spent coaching middle-school football, fathers typically spend more of their time engaged in vigorous play than do mothers, and play a uniquely physical role in teaching their sons and daughters how to handle their bodies and their emotions on and off the field. Psychologist John Snarey put it this way in his book, How Fathers Care for the Next Generation: "children who roughhouse with their fathers... quickly learn that biting, kicking, and other forms of physical violence are not acceptable."

Encouraging risk: In their approach to childrearing, fathers are more likely to encourage their children to take risks, embrace challenges, and be independent, whereas mothers are more likely to focus on their children's safety and emotional well-being. "[F]athers play a particularly important role in the development of children's openness to the world," writes psychologist Daniel Paquette. "[T]hey also tend to encourage children to take risks, while at the same time ensuring the latter's safety and security, thus permitting children to learn to be braver in unfamiliar situations, as well as to stand up for themselves." In his review of scholarly research on fatherhood, he notes that scholars generally find that dads are more likely to have their children talk to strangers, to overcome obstacles, and even to have their toddlers put out into the deep during swim lessons. The swim-lesson study, for instance, which focused on a small sample of parents teaching their kids to swim, found that "fathers tend to stand behind their children so the children face their social environment, whereas mothers tend to position themselves in front of their children, seeking to establish visual contact with the children."

Protecting his own: Fathers play an important role in protecting their children from threats in the larger environment. For instance, fathers who are engaged in their children's lives can better monitor their children's comings and goings, as well as the peers and adults in their children's lives, compared to disengaged or absent fathers. Of course, mothers can do this, to an extent. But fathers, by dint of their size, strength, or aggressive public presence, appear to be more successful in keeping predators and bad peer influences away from their sons and daughters. As psychologist Rob Palkovitz notes in our book, "paternal absence has been cited by multiple scholars as the single greatest risk factor in teen pregnancy for girls."

Dad's discipline: Although mothers typically discipline their children more often than do fathers, dads' disciplinary style is distinctive. In surveying the research on gender and parenthood for our book, Palkovitz observes that fathers tend to be firmer with their children, compared to mothers. Based on their extensive clinical experience, and a longitudinal study of 17 stay-at-home fathers, Kyle Pruett and psychologist Marsha Kline Pruett agree. In Partnership Parenting they write, "Fathers tend to be more willing than mothers to confront their children and enforce discipline, leaving their children with the impression that they in fact have more authority." By contrast, mothers are more likely to reason with their children, to be flexible in disciplinary situations, and to rely on their emotional ties to a child to encourage her to behave. In their view, mothers and fathers working together as co-parents offer a diverse yet balanced approach to discipline.

The Difference Good Dads Make

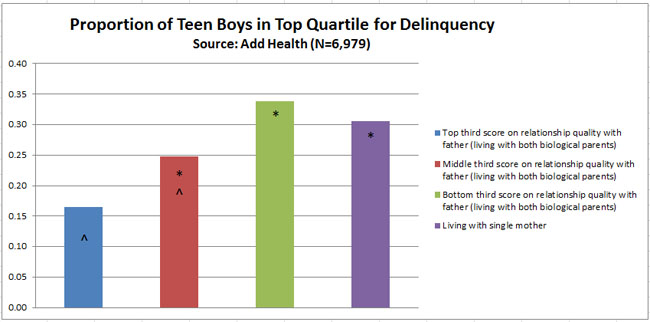

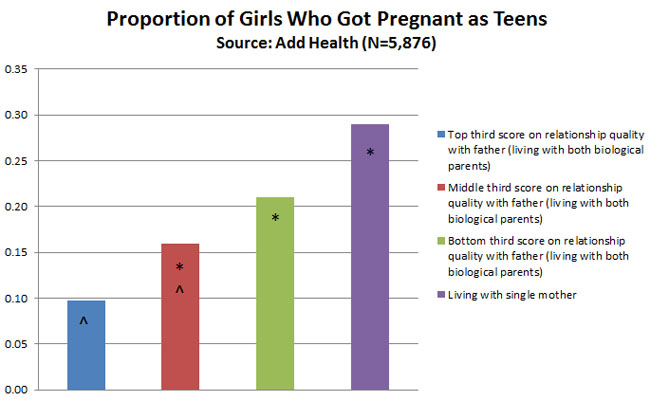

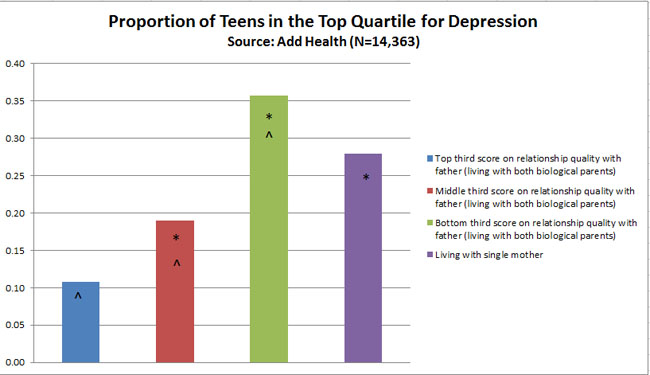

The contributions that fathers make to their children's lives can be seen in three areas: teenage delinquency, pregnancy, and depression. Here, to illustrate the connection between fatherhood and child well-being, I compare adolescent boys and girls who fall into one of four categories: those living in an intact, married family with a high-quality relationship with their father (top third), or an average-quality relationship with their father (middle third), or a low-quality relationship with him (bottom third), or living in a single-mother family. Relationship quality was measured by a scale of three items tapping a child's assessment of his father's warmth, communication skill, and overall relationship quality.

Delinquency Boys who enjoy average and especially high-quality relationships with their fathers in an intact family are less likely to engage in delinquent behavior. For instance, boys who enjoy high-quality relationships with their fathers are about half as likely to be delinquent, compared to boys being raised by single mothers or by fathers in intact families who only have low-quality relationships with them.

Teenage Pregnancy Dads also seem to matter for daughters. Here, teenage girls living with their father in an intact family and enjoying at least an average-quality relationship with him are about half as likely to become pregnant as teenagers, compared to girls living with a single mother, or who only have a low-quality relationship with their father in an intact family.

Depression And for both boys and girls, a high-quality relationship with dad is associated with less depression. Such teenagers are less than half as likely to end up depressed, compared to their peers in single-mother households, or intact homes where dad only has a low-quality relationship with them. (Note also that most of these associations remain statistically significant after controlling for maternal education, household income, race/ethnicity, and respondent's age.)

The story told by this data, then, suggests that there is a case to make against the fathers who fail to have good-enough relationships with their children. At least on these outcomes, single mothers do about as well for their children, compared to dads who have poor-quality relationships with their children. By contrast, great, and even good-enough dads, appear to make a real difference in their children's lives.