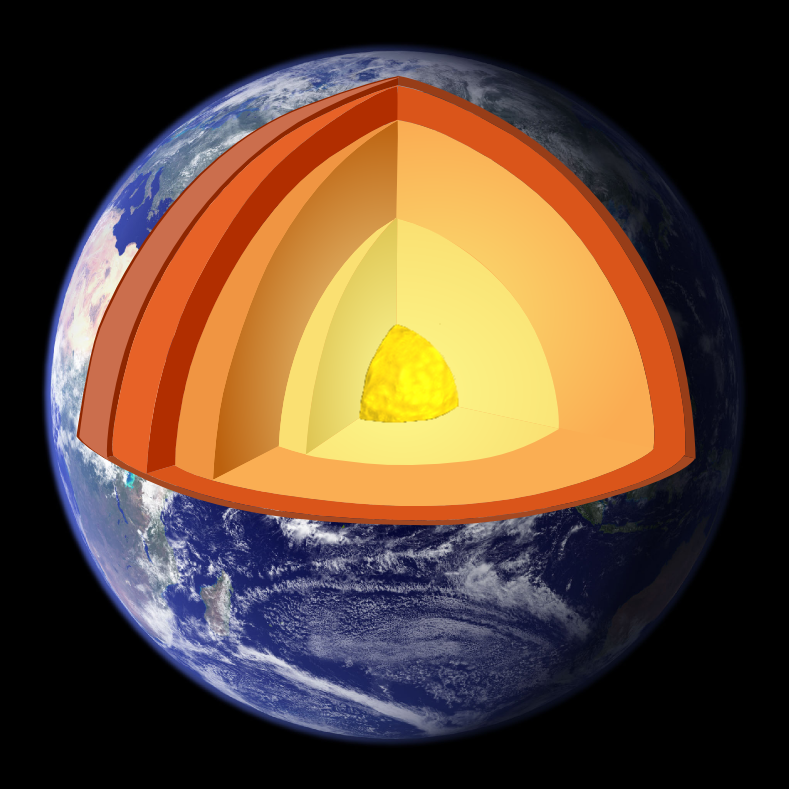

On the seafloor at a location in the Indian Ocean called the Atlantis Bank, about 800 miles southeast of Madagascar, scientists are working to drill 1.6 miles through the Earth's crust to reach the mantle and recover a sample for the first time. Though fragmented pieces of the mantle that were uplifted to the surface by ocean ridges or spewed out by volcanoes have been recovered in the past, the samples have been significantly altered by their journeys to the surface. A pure sample of the mantle—which makes up about 68 percent of Earth's mass and about 85 percent of its volume—could help scientists answer a number of questions about the way material flows between Earth's core and crust. The composition and mineralogy of the mantle will also offer clues about the early formation of the Earth and how it separated into the tiered planet we have today.

As Sid Perkins writes for Smithsonian, scientists have been trying to get their hands on a chunk of the mantle for over 50 years. In 1961, geologists of the now-dissolved American Miscellaneous Society began a project to drill into the Earth's mantle off the Pacific coast of Southern California. But their efforts, and others like theirs, were soon overshadowed by the space race of the 1960s. NASA soaked up most of the country's research funds, technical problems with drill designs were common, and efforts to drill deep into the Earth stalled out.

But in early December, a team led by Henry Dick of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Chris MacLeod of Cardiff University in Wales shipped out on the JOIDES Resolution research vessel to try to get one step closer to acquiring an unblemished piece of the Earth's mantle. At the Atlantis Bank site, where the crust is cool and thin and ripe for drilling, the research team hoped to drill about halfway to the mantle in the first phase of a planned multi-expedition project.

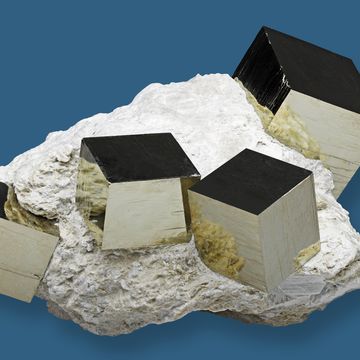

The first phase of the project at Atlantis Bank is currently wrapping up, and although they didn't reach their target drilling goal of 4,265 feet, they did retrieve the largest diameter piece of the Earth's crust ever recovered. The composition of the Earth's crust can vary drastically depending on the location it was recovered from, making the 7-inch diameter, 20-inch long chunk of cooled magma a valuable sample.

Multiple broken drill bits mean that the team only reached a depth of 2,330 feet below the sea floor, but in addition to the large piece of crust recovered, the expedition provided valuable trial-and-error knowledge for a future expedition. Another trip to the Atlantis Bank to attempt to drill the full 1.6 miles to reach the mantle has already been approved, though it could be as many as five years before the expedition team returns due to high competition for time with the ship.

Material in the mantle circulates in much the same way that ocean currents do, though at a much much slower pace. Cool material near the border with the crust slowly sinks down toward the core, while hot material near the border with the core rises toward the surface. A full trip from crust to core and back takes an incredibly long time, however, perhaps as long as 2 billion years.

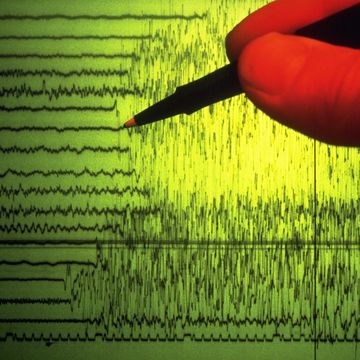

We have some estimates about the density and composition of the mantle from indirect geological methods. The speed that seismic waves travel through the Earth can give us clues about the density and viscosity of the mantle in various locations. The rate at which the crust has risen after ice-age glaciers melted away can give us even more clues about general characteristics. We can even infer what types of minerals make up the majority of the mantle, a hodgepodge of silicate rocks, by studying the magnetic and gravitational fields of the Earth.

With a pure sample of rock from the mantle, researchers will be able to confirm or invalidate the indirect methods we currently use to study the middle section of the Earth, opening the door for new research. Given that crust samples turned out to be significantly different from what researchers expected, we can safely assume that a mantle sample will provide some surprises as well. And a hole that reaches all the way down into the mantle will be of great interest to seismologists and other researchers who could lower instruments to directly measure various properties.

"Future expeditions may be dropping instruments down the hole for years to come," MacLeod told Smithsonian.

Source: Smithsonian

Jay Bennett is the associate editor of PopularMechanics.com. He has also written for Smithsonian, Popular Science and Outside Magazine.