By the time Major John I. Nevin of the 93rd Pennsylvania took part in the fall 1863 Bristoe Station Campaign in Virginia, his military service would have satisfied most volunteers. Nevin, a native of Sewickley, Pa., near Pittsburgh, enlisted in the 28th Pennsylvania in July 1861, only to be captured by Captain Elijah White’s guerrillas in February 1862 near Harpers Ferry. After serving time in Rebel prisons in Richmond, Va., and Salisbury, N.C., Nevin was paroled in August 1862. He returned home and promptly raised Independent Battery H of the Pennsylvania Light Artillery and made himself the unit’s captain.

That did not go well. While his battery was training outside Washington, Nevin ran afoul of Brig. Gen. William F. Barry. The Regular Army brigadier had Nevin arrested in February 1863—for what exactly, existing records do not indicate—and the captain resigned on February 13 in order to avoid a court-martial.

But Nevin gave it one more shot, and returned to the front as the major of the 93rd Pennsylvania of the Army of the Potomac in May 1863. That regiment had a dysfunctional high command with no lieutenant colonel and a colonel, James M. McCarter, who was often drunk. So essentially Nevin led the regiment, raised in eastern Pennsylvania, through the Gettysburg Campaign. McCarter was forced to resign in August 1863, setting the stage for Nevin to have unfettered command of the 93rd during the Bristoe Station Campaign.

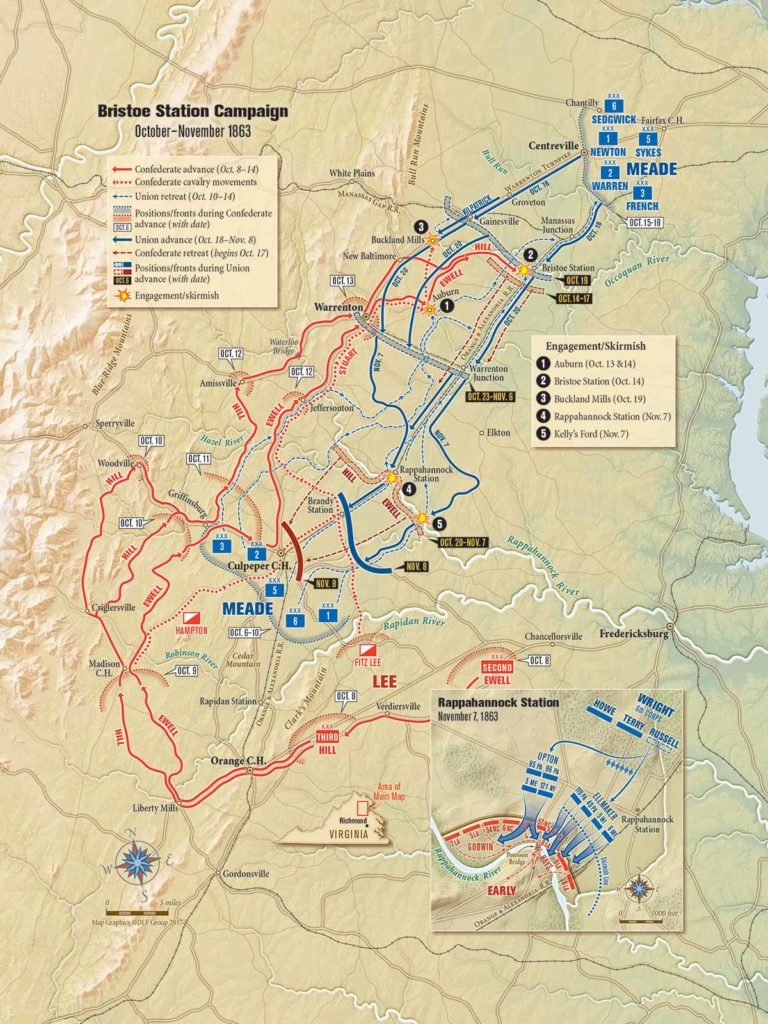

That October 1863 campaign was mostly a war of maneuver and comparatively small fights between two armies still recovering from Gettysburg trauma. When the campaign began, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade’s army was in Virginia west of the Rappahannock River, but General Robert E. Lee attempted to turn the Army of the Potomac’s right flank, and Meade retreated to the east along his Orange & Alexandria Railroad supply line. The Union commander moved quickly to avoid being brought to battle on ground not of his choosing.

Major John Nevin’s diary entries chronicling the campaign begin on October 13. The 93rd Pennsylvania, part of Brig. Gen. Frank Wheaton’s 3rd Brigade, of Brig. Gen. Henry Terry’s 3rd Division, of Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick’s 6th Corps, had left the vicinity of Culpeper, Va., on the 12th, and by the 13th had crossed the Rappahannock and was trudging eastward along the O&A line with most of the Army of the Potomac. Nevin was an educator and newspaper reporter in civilian life, and the entries in his diary, held at the Senator John Heinz Regional History Center in Pittsburgh, are entertaining and journalistic. Some punctuation, paragraph breaks, and capitalization are added for clarity. Misspelled words have been corrected when they cause confusion. Otherwise the entries are reprinted as written. In this first entry, Major Nevin describes the retreat and hearing fighting known as the Battle of Auburn, when Confederate cavalry clashed with the 2nd Corps to the north of the railroad.

October 13

Last night we were twice aroused and formed into line on account of firing of the pickets. About three A.M. two or three distinct volleys were heard in the direction of Bealtons station where the wagon train of the whole army lay. Suddenly there “arose so wild a yell” “As all the fiends from heaven that fell had pealed the banner cry of hell.” That describes the noise that arose in the wagon park. We were too distant to hear the distinct elements of those ominous sounds of a stampeded wagon train, but the curses (rendered faint of distance) and yells of the frightened teamsters and the varied shrieks and brays of the excited mules, the rattling of the wagons, all mingles and contributed to produce one of the most awe inspiring noises I ever listened to. But Stuart had not got amongst them after all. At seven oclock we received notice to fall in to our place in brigade as it should march by, for the Army of the Potomac was once again about to perform its accustomed brilliant maneuver of changing its base.

Marched pretty steadily all day tho’ slowly, as the trains moved in front for fear of the enemy. At Bristoes Station we saw pretty much the entire wagon train of the army, the open country for miles around was almost literally packed with the wagons; two huge parks of commissary wagons were evidently arranged to be burned if they could not be got away; from most of the other parks the trains were beginning to project into the space toward Washington looking for all the world like so many white jointed snakes slowly pushing forward their heads from their massive coils. We apparently getting tired waiting, push forward our long blue column thro’ the wheeled labyrinth and by it, in the depth of the wood in front.

A dreadful night march ensued. Very cold too, and tedious in the extreme. The wagon train, still in front from some unaccountable reason went forward at a snails pace over what seems to us an excellent road. Such marches are demoralizing. Every bodies patience becomes completely exhausted and a column of solid cursing, mental and expressed, from the Brigadier General foaming at the van, with his horses nose pressed against the tail board of the last wagon down, by grade, to the private soldier who after standing in ranks twenty minutes, moves forward some ten paces, only to be brought up in a halt again, against his file leaders knapsack, for another twenty minute stand, rolls up to heaven, as a testimony that the Army of the Potomac is oblivious to the incapacity that has sometimes guided it, and paralized its gigantic strength. As to the good accomplished by the operation the best commentary on it was the continuous line of fires on either side of the road indicating the enormous number of stragglers who were going to the right and left, by file into line, into independent bivouacs there to rest and cook coffee, sleep, and in the morning jog on a couple of miles and merrily fall into the ranks of the weary sleepless ones who have been toiling forward, all night, in their places. Five miles in eights hours we made last night. There I’ve had my grumble.

Yesterday we marched abreast of a wagon train, a wagoner dropped his whip, stopped his wagon jumped off and got it–then moved on. I saw that momentary stoppage travel back, along the long line behind, like a wave on the sea, or a shake in the clothes lines, and clear to the end of the train, miles back that little delay comes back and the following soldier stops and wonders what it means. Bivouaced at 4 A.M. Oct 14th

October 14

General sounded at 5.30 A.M. and the weary soldiers prepare again to march. No rest they say until we reach Centreville, for they say it is a race between Lee and Meade, which shall get there first. Devil take the hindmost. I am detailed for officer of rear guard to-day to keep up the stragglers. Usually that is a detestable duty, but to-day there is little difficulty for a powerful rearguard is booming still farther in the rear, that stragglers usually heed. The bull dogs of the light artillery are barking quite briskly. At evening, Centreville, from Licking Run twenty seven miles. We bivouacked on the Northern slope of that natural fortress and from its’ ramparts we gazed during the “hours of the setting day,” long and anxiously towards Bristoes Station, whence came increasing sounds of the conflict. The 2nd Corps are said to be our rear-guard and it would seem that they are playing quite earnestly the old war-music of the cannon and the musket. As the twilight deepened the flashes of lightening could be seen that accompany the thunders….

October 16

An hour before Sunrise We fall into line, and stand silently to arms, until the sun has risen….Many a time when thus silently awaiting the expected attack of the wily foe, watching the red sun after gradually tingeing the gates of the east, at length rise solemnly above the surrounding hills, strange thoughts of life, and death and eternity would occupy my mind.

….Presently the “hunky boy” as the little sharp newspaper boy [is known] makes his appearance in the very front. How venture some they are! I remember it was July 3rd at Gettysburg amid shot and shell the hunky boy comes up with the Baltimore papers. I paid him ten cents, for one in spite of the ordinance, for his energy….

October 18

Begin to think the Rebs have left. Heavy firing tho’ yesterday evening on the extreme left. Got a negro servant—he came within our lines, last evening our regiment being on picket—he had run away from his master—master had found he was stealing his tobacco, set a steel trap for him—Nig. discovered the trick set the trap for his master at the corn crib, and when master reached for the corn, lo! The trap caught him, So the servant “hired for life” deserted. And that is Wash’s history. Virginia n——s exercise ludicrous freedom in names. I’ve seen a swarm of them at a cabin and asked their names. “I’m Buck, he’s Jim and she’s Dinah.” “Yes, Buck but I want to know your last name, you’re all brothers and sisters ain’t you?” “yas mass’r. Jim’s last name is Johnson, mine’s Jones, Dinah her’s Williams.” etc.

October 19

On the march again striking tents in a violent shower. We marched off in the mud in the direction of the old Bull Run battle field. Presently we began to tread its classic ground….As we passed over the battlefield and the morning sun, shone out from amongst the clouds smiling on us as we passed thro’ those solemn hills and dales as if to assure us, we should have “no more Bull Runs,” our eyes would turn to the right and left to see the head boards of the shallow buried combatants….

Shallow–buried! Yes, yonder an arm protrudes from the “other clay,” and covered with its tattered habiliments of blue, gesticulates wildly, on the autumn wind, as if to bear witness that not yet has the martyrdom of its owner then been avenged. How long! Further on, close, almost beneath the feet of the marching column, grins a white skeleton face, with perfect teeth, out of his grave to heaven.

We halt at Gainesville from Chantilly 10 miles. As we led the Corps today we frequently had opportunity while crossing the higher grounds, to look back and catch grand views of the advancing columns, far as the eye could reach back wards, until we could not see the men but only the bayonets glisten….We met the returning masses of the Cavalry just coming in from the front. They report us “just in time.”

We ford a deep stream, every body getting their feet wet, and then lie down on our arms in the still October night. Good hardening or softening regimen! Officers without blankets or overcoats too, as the pack mules are forbidden to come to the front in the present perilous emergency! Well! I have my overcoat behind my saddle, and a gumblanket before so I shall court Morpheus if possible anyhow! For tomorrow we will either have a big fight or a long march—most probably the latter, as the impression gains ground that Lee is far away, and that Stuarts cavalry which have today whipped Kilpatrick (Kill-Cavalry his men call him) until they felt the advance of our infantry, will be many miles toward the Rapidan tomorrow.

October 20

From Gainesville to Warrenton, 11 miles. Near New Baltimore we saw the “signs” of the Cavalry fight of yesterday, dead men by the road side, one wounded man over on the hill, the red flag of a hospital, over a neighboring barn…..The boys spoil my horse. They’ve got him very fond of crackers, by letting him nibble at them as we march along, and they got him crabbed by tantalizing him too, by with holding the titbits, they have taught him to open their haversacks and help himself which trick he avails himself of very frequently in the dark. He is a great favorite of Company B behind which is his place and which he knows as well as any-one. And if taken away from the column, will gallop back and fall in, as if afraid of being lost! We camp or rather lay down at midnight by the roadside.

October 22

At noon, fall in to march “in the direction of our old camp West of Warrentown,” So after making a narrow ellipse we are going back to one of our homes!….Some one irreverently says “the campaign of the two dogs” “Bow wow” say dog 1. Dog Two runs, dog 1 following nipping him by the tail, dog two turns round. “Bow wow,” dog one runs with dog two nipping his tail and so on.

November 7

So after a rest of a couple of weeks—after building huts again and chimneys, again with a sigh we have to pack up to the tune of the “General,” sip our shivering cup of coffee by the light of the “chaste stars” and the “sickle” moon and the glow of the rosy east, all at 4:30 a.m. A glorious morning, but exceedingly cold! Capt. R has a presentiment that this time, he’ll be shot.

….Slowly we marched along the railroad toward Rhappahanock [sic] Station, never dreaming of meeting any enemy this side of the river. Suddenly as we emerged from the edge of a belt of woods, we see our outmost pickets within a couple of hundred yards and right beyond, the opposing pickets of the “Johnnies.” Lines of battle rapidly forming on all sides of us and presently our column too is unrolled into line. Our skirmishers commence to advance—supports quickly follow—batteries trot out to different positions, and thus suddenly are we rushed into the midst of a battle. Now the skirmishers clash, and rattle goes the old familiar musketry—great guns belched forth, shells burst in mid-air, and the evening sun becomes dim in the thickening smoke. Suddenly our brigade bugle sounds “attention.”

Genl Terry deploys us into masses, and in two lines of battalions in mass we move into the “sulphurous canopy.” Cooly as on parade our brave boys move forward keeping an excellent alignment, shells burst in their very faces scattering their deadly spray right into the masses but none wavered–there was no confusion, except that caused by the falling of the stricken. “Short and decisive” was the battle….A brilliant little battle for the Sixth Corps. The fruits were 1,300 prisoners, 100 killed and wounded, 7 pieces of artillery, loss of about 500 killed and wounded.

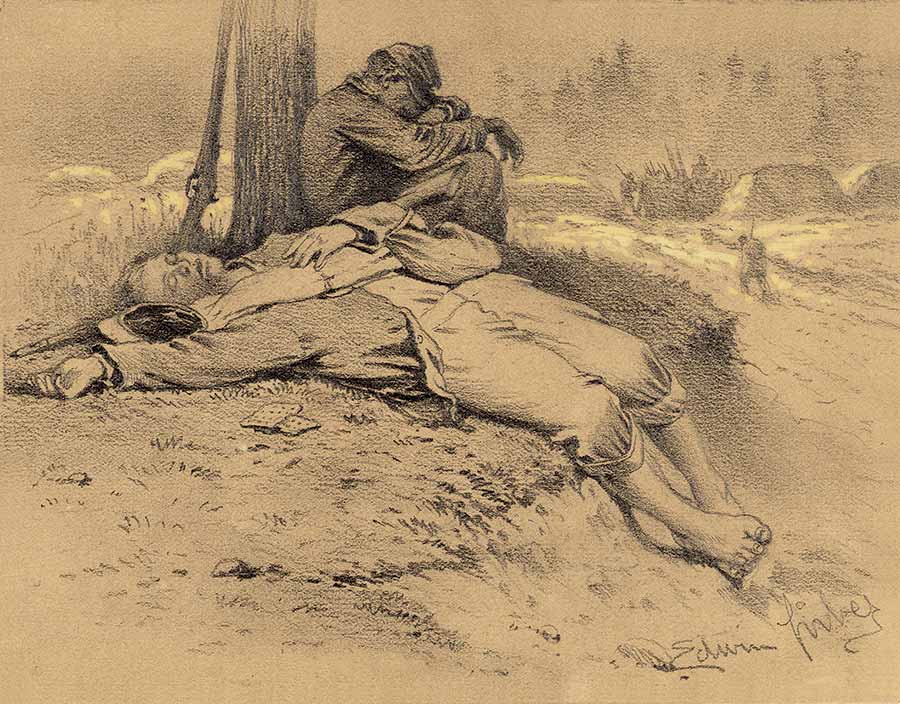

We slept on our arms. No fires. The heaviest fighting was right thro’ our comfortable old camp that we left so regretfully some weeks ago. The Rebs, made our soldier-palaces their homes, and some of them their graves. Poor fellows! I read some of their letters taken from their bodies. Home letters and love-letters with their simple incidents of domestic life and domestic love brings home to ones mind the horrible nature of the struggle we are waging. Verily there be mothers and wives in the south as well as in the north that wish this cruel war were over.

The prisoners taken are mostly North Carolinians. Their letters show disaffection to the Confederacy. They are bitter toward the other Southern States thinking that they are imposed upon. In conversation with a big North Carolina Sergeant, I asked why we didn’t meet more Virginians in battle. “Oh” he said “they are scattered thro’ the South doing provost guard duty and such like.” Distance march is 16 miles.

November 8

Again away by starlight on the Falmouth road but just as the scenery began to liken itself to the old Falmouth type of pine woods…we struck off to Kelly’s Ford, and after winding somewhat unaccountably jostling with several different wagon trains, we finally brought up in a confused heap in the graveyard of Mount Holly Baptist church. We remained here long enough to go into the church—(now a temporary hospital as quite a battle was fought here yesterday by the 3rd Corps) and see a couple of amputations and other agreeable sights—also the burial of a North Carolina captain and private—with their martial cloaks [English overcoats] around them. A hospital steward of the 63rd Pa was busily engaged lettering head boards not only for the dead but for those soon to die.

“There Jim” says he coolly “that’ll do for he Captain get a couple of fellows to carry him out I’ll go right to work on one for that big Georgia Sergeant with both legs shot off, he’ll not survive amputation more than ten minutes longer, I must hurry up, too, for you Carolina boy with the ball in his bowels will be ready for me next.” “You see” said he to me as I admired his fine lettering, “I want to show these fellows, that we can bury them better than they bury us.” “Yes bury his boots with him, Bill and that fine overcoat too; it’s their trick to strip the dead, tho’ I don’t blame the shivering devils much either.”

The Generals Aid finally extricated us regiment by regiment from the mass, and assigned us our camping grounds for the night. “So” thought I “nothing more tonight!” So we heaped up a great big fire, cooked our meat and coffee, spread our blankets for the night….

Dana B. Shoaf is the editor of Civil War Times magazine.