Does “scone” rhyme with the word “gone” or “cone”? Is “last” pronounced with a long a, as if an r follows it?

Researchers from the University of Cambridge, along with academics from the universities of Zurich and Bern in Switzerland, are using these (often contentious) questions of how Brits pronounce words to try to map how and where the English language has changed.

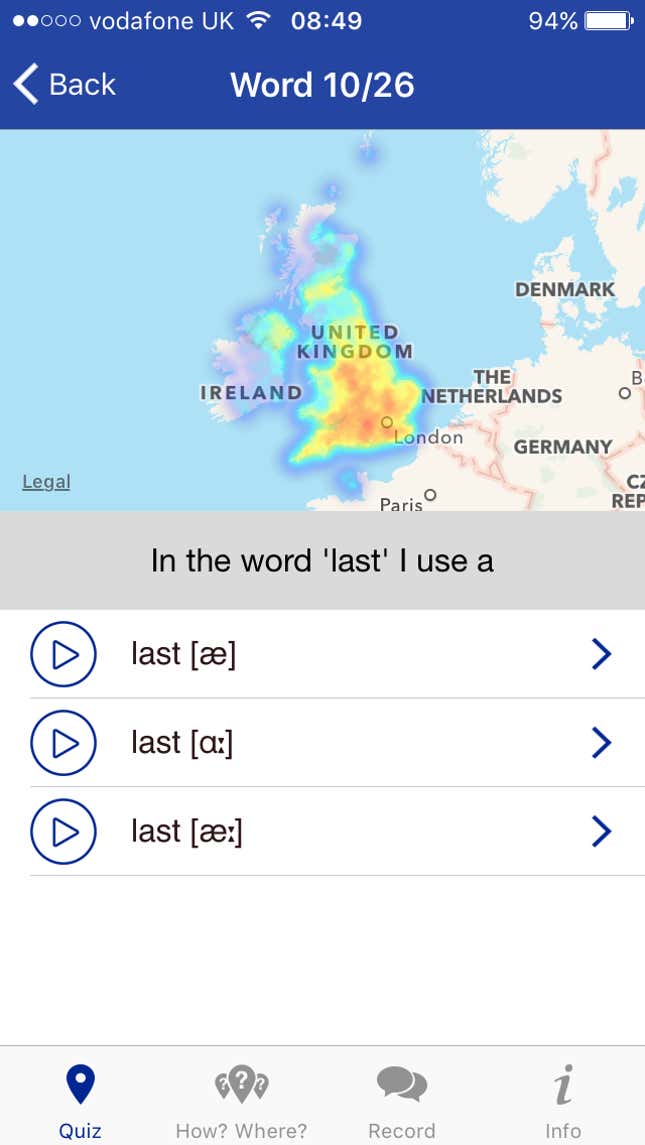

The team recently launched a smartphone app that attempts to guess a user’s regional accent. A user will take a quiz in which they answer how they would pronounce 26 different words, colloquialisms and phrases before the app guesses where in England they are from.

Users are then given the option to share with researchers data on their location, age, ethnicity, education, and gender, as well as how many times they have moved in the last 10 years. “We want to document how English dialects have changed, spread, or levelled out,” said Dr. Adrian Leemann, a researcher at the Department of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics at Cambridge.

The app follows a previous German-language app developed by the team to gauge how the language had evolved in German-speaking Switzerland. “Our research on dialect data collected through smartphone apps has opened up a new paradigm for analyses of language change,” Leeman claimed. In the study, data from almost 60,000 speakers revealed that phonetic variables (i.e. the sound of a word) stayed stable over time, but lexical variables (i.e. the meaning of a word) seemed more prone to change.

Using such apps to document language change—as opposed to language learning or translation—is still new. One of their strengths is they help gather data from a broader, more diverse pool of people more quickly, explains Tam Blaxter, one of the researchers from Cambridge University. “Traditional survey methods have tended to concentrate on older, rural people who are not very geographically mobile, whereas digital methods reach younger, more educated and mobile people. As a result, we can get insight into the way a very different sector of the population speaks than previously.”

Still, the academics admit that there are some caveats: researchers will only have a limited knowledge of users’ linguistic backgrounds, and this data itself is self-reported.

Dr Leeman also conceded that the English language app’s best guesses might not always be accurate. “If the app does not guess correctly, it is probably because the dialect spoken in your region has changed quite a lot over time.”

I found this myself when testing the app. Growing up between Cambridge and London, I’ve got what’s commonly referred to as an Estuary accent found in the southeast of England. The app got reasonably close by suggesting I was from the south coast—but its guess of Jersey, in the Channel Islands, was a bit of a wildcard.

This story was updated to include comment from Tam Blaxter from the University of Cambridge.