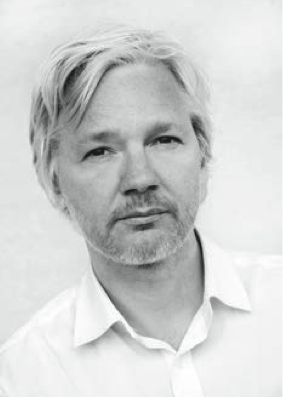

It would be too much to say that WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange feels optimistic. He's been holed up in the Ecuadorean embassy in London for more than two years now, with cameras and police—"a £3 million surveillance operation," he calls it—just meters away.

"There's a sense of inevitability now," Assange said when we asked if his situation might change.

Assange: "The situation is clarifying politically and legally."

Ars: "I just want to be clear on this point—are you saying you're hopeful you'll be free soon?"

Assange: "I wouldn't say hopeful. I would say it's inevitable. It's inevitable that we will win the diplomatic standoff we're in now."

It's getting late in London, where Assange is doing a barrage of press interviews on the eve of his new book, When Google Met Wikileaks (it goes on sale in the US later this week). We called at the agreed upon time, and a man who didn't identify himself answered the number, which was for a London cell phone. He said call back in five minutes, and only then was the phone finally handed to Assange.

We're supposed to focus on the book. But first, we want to know what life trapped in the embassy involves—where does he eat, sleep, do laundry? What is the room he's in now like?

"For security reasons, I can't tell you which sections of the embassy I utilize," he said. "As to the rest, in a way, it's a perfectly normal situation. In another way, it's one of the most abnormal, unusual situations that someone can find themselves in."

Assange ushered WikiLeaks through several massive leaks of secret US government reports and a tumultuous relationship with some prominent newspapers. first came the disclosure of hundreds of thousands of military reports on the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts, then a leak of more than 250,000 diplomatic cables from the State Department.

He sought asylum from Ecuador when he was on the verge of being extradited to Sweden to face sexual-assault charges in that nation. If he leaves the embassy, he'll be arrested, although it isn't clear where he'll be sent first. It's widely assumed the US has an ongoing investigation into Assange over the leaks.

Asked about what his future outside the embassy walls might look like, he stays focused on the legal battles ahead. "We have a lot of dominos to knock over," he said. "There are three or four different legal cases going on, and technical means to obstruct the asylum."

He knows his travel will always be circumscribed to a degree, but Assange seems comfortable with that. He's cognizant of the parallels between his situation and that of Edward Snowden.

"He has freedom of movement," Assange acknowledged. "But his freedom of movement excludes a number of countries which can be pressured by the US, and that's also true for me."

His voice sounded scratchy as he spoke to Ars about how Google and its chairman Eric Schmidt were at the "center of American power," pushing an "aggressive new ideology." In the background, another phone started ringing. Assange wasn't distracted. Half prisoner, half professor, he kept talking in the same slow cadence, with an insistent and didactic focus on making his point.

Breaking the Google Glass

The next several chapters—the bulk of Assange's book—are actually a transcript of his single meeting with Schmidt in June 2011, when Schmidt interviewed him for The New Digital Age. This heavily footnoted section is followed by another short essay, "Deliver us from 'Don't Be Evil,'" in which Assange invites readers to look at how WikiLeaks was portrayed in Schmidt's book and "compare against the source material."

It gives the distinct impression that Assange seems fairly obsessed with Schmidt. We asked him to explain his book's intense focus on the man.

"Schmidt and his network represent what is becoming the center of American power," he said. "This is not a group of people who, by their personalities, are necessarily bad people. But they happen to have an aggressive new ideology that is able to amass significant amounts of power—precisely because it is represented by individuals that dress themselves in a mantle of reformist rhetoric. Now it's merged with traditional forms of power, mostly based in Washington. It's the most modern form of company structure that we have."

Google has doubled its market capitalization in a few years, and "its reach now extends to every person in one way or another," says Assange. It extends to the million-plus people each day who activate Android phones. They "may not think they're using the Internet," but of course, they are.

"Out of my comfort zone"

Assange speaks of his book as a kind of diagram of how power works in the age of the Internet: an analysis of the "positioning" of Google and Schmidt, he explained. But plenty of it reads like good, old-fashioned score-settling, albeit with an academic veneer. Assange describes how he was excited to get his hands on a copy of Schmidt's book and "had someone carry a copy past the police cordon so I could read it."

Yet Assange seems shocked that book—penned by one of Silicon Valley's wealthiest executives and the government functionary he brought into the Googleplex—isn't sufficiently revolutionary. Having smuggled a copy into the embassy that has become his prison, Assange condemns Schmidt's work as having "failed to deliver—failed even to imagine a future, good or bad, substantially different to the present." He writes:

The book was a simplistic fusion of Fukuyama “end of history” ideology—out of vogue since the 1990s—and faster mobile phones. It was padded out with DC shibboleths, State Department orthodoxies, and fawning grabs from Henry Kissinger. The scholarship was poor—even degenerate. It did not seem to fit the profile of Schmidt, that sharp, quiet man in my living room.

Ultimately, Assange completes his journey and grows to understand the meaning of Schmidt's visit to see him. The "burgeoning digital superstate" of Google "was offering to be Washington's geopolitical visionary." Schmidt, in a sense, was acting—doing "back-channel diplomacy" for the government. "While WikiLeaks had been deeply involved in publishing the inner archive of the US State Department, the US State Department had, in effect, snuck into the WikiLeaks command center and hit me up for a free lunch," writes Assange.

Despite his belief that Schmidt and Cohen were mining him for information, Assange rates their performance—and his own—as stellar:

To their credit, I consider the interview perhaps the best I have ever given. I was out of my comfort zone and I liked it. We ate and then took a walk in the grounds, all while on the record. I asked Eric Schmidt to leak US government information requests to WikiLeaks, and he refused, suddenly nervous, citing the illegality of disclosing Patriot Act requests. And then as the evening came on it was done and they were gone, back to the unreal, remote halls of information empire, and I was left to get back to my work.

When Schmidt's book published, it was met with "only uncomprehending praise," Assange seethes. That's an odd thing to say, since Assange himself was invited to critique it in the best-known English language newspaper in the world. Assange's New York Times essay on the book, which he slams as a "blueprint for technocratic imperialism, from two of its leading witch doctors," was likely read by at least as many people as read Schmidt's book.

But that was insufficient for Assange, so he has now published a book-length assault on Schmidt and his connections. It's a single-minded tome: an angry, erudite, unredacted letter from the world's most unusual prisoner.

"A place where politics happens"

Assange does bring up important issues. To him and his sympathizers, the erosion of privacy is making the free world look more totalitarian, not the geeky paradise envisioned by Internet utopians. But it's hard to escape the feeling that his book is essentially an extension of points he made effectively in his 2013 Times piece. The added depth feels like fist-banging, not proving points.

In a way, the intense focus on Google prevents Assange from telling his own story in a meaningful way—but that was never his intention. It's telling that Assange, having readied an autobiography together with a ghost writer, decided to spike the work after seeing a first draft. "All memoir is prostitution," he declared to his publisher in 2011, seeking to cancel the contract. Months later, Canongate Books went ahead and published the "Unauthorized Autobiography" without his consent.

In Assange's mind, the redactions of the leaked material made by the world's newspapers were massive, far more than what was needed. In his talk with Schmidt, he describes The Guardian removing "two-thirds of a cable about Bulgarian crime," including the names of "all the mafiosi who had infiltrated the Bulgarian government... They are worried that they might get sued for libel in London." The Irish Independent redacted the names of corrupt companies, "even though it's a very good newspaper and the journalists are totally onside." Overall, it amounts to "incredible self-censorship."

Assange told Ars that WikiLeaks could have done a better job policing the media outlets he worked with. They agreed to redact only for "human rights reasons," he said, but ultimately "they redacted for political reasons" as well.

Assange describes WikiLeaks' role as a historical one, but it's hardly complete. One doesn't have to look any further than today's headlines about the FinFisher leak to see that the site is still making news.

"WikiLeaks has performed an important role in demonstrating what can be done and the technology to do it," he said. "That's caused others to emulate some of our methods.

"Most importantly, all of this has inspired other whistleblowers to come forward in different ways. It's inspired people to believe that the Internet is a place where politics happens. Politics in the sense of, being a place where society is shaped. I think if you go back five years, the Internet was an apolitical space."

To close, we asked him about geography. He didn't see much irony in the fact that advocates for transparency and liberalism, like himself and Edward Snowden, have ultimately found protection from regimes that aren't very liberal.

"Well, Ecuador wasn't thought of as anything until it gave me asylum—then there was a campaign to describe it as illiberal," he said. "Asylum is a serious business. People seeking political asylum, by definition, are doing so to avoid persecution. They go to the country most likely to protect them from that persecution, out of the countries that feel strong enough, or independent enough, to do so.

"Edward Snowden and I, and some others who didn't manage to get out, have become Western political dissidents. There is a power alliance through the major institutions of the West—that's why they call it the West. So it's only going to be non-Western countries that are able to offer asylum."

reader comments

124