The college selection process was both a thrilling and troubling experience for me. It was thrilling in that my dreams were coming true -- all of my hard work was paying off and my life would soon transform incredibly. But, it was troubling in that I felt insecure about the college to which I was heading. For me, it had come down to Emory and Morehouse. Emory was my dream school -- I loved the Black faculty members I'd met, the beauty of the campus, the style of the facilities and the prestige associated with the school; Morehouse was my less desired, convenient back up. However, my Emory dreams were crushed when I received my financial packages from both schools. While Morehouse offered to almost fully fund my attendance, Emory barely gave me a quarter of its cost. The decision was made for me.

The Monday following the decision, I held my head low in all of my classes. To tell people that I couldn't go to Emory -- my dream school, the school I'd bragged about all year -- because of financial reasons felt disappointing. To tell people that I'd have to go to Morehouse instead -- my back-up school, the school that none of my non-Black friends and only a couple of my teachers had heard of -- felt humiliating. I remember having classmates say "Marcus, you're smart! Don't go to a Black school." I remember teachers who let out sighs of disappointment when I told them where I had to go. I remember my Black friends who were heading to Chapel Hill say that they would have "never applied to an HBCU." I even remember a friend's dad -- who went to an HBCU -- advise against going because he wouldn't hire a job candidate from an HBCU since it was too embarrassing that his other colleagues weren't familiar with the institutions. And, I remember internalizing all of it. As a first generation student, I relied heavily on the opinions of friends, teachers and mainstream media sources -- no matter how uninformed or culturally incompetent -- to inform my process.

So, I pouted every day for the rest of senior year. I pouted at graduation. I pouted driving past the Emory hospital sign on I-85 South en route to Morehouse. And, I pouted pulling up to my first year residence hall. It wasn't until after the first night of New Student Orientation (NSO) Week -- after witnessing Segun Idowu, Colin Bent, Bryson Green and other brilliant upperclassmen present themselves as possibility models on stage through short speeches/poems about what Morehouse meant for them -- that I began to fall in love with the 'House that I call home today. I remember exiting King's chapel after the ceremony, locking eyes with my father and saying "Yep! This is it!"

My newfound love for its legacy, its sons and its mission quickly dissolved most of the insecurity I felt about Morehouse. But, some of it was still there -- I still had Black friends at predominately White-serving Institutions (PWIs) quickly remind me that their coursework was more advanced, that they had more resources, and that they hadn't taken the "easy way out." Though Morehouse filled my heart, my mind anxiously clung to the idea that PWIs were the real schools, the standard to which all other institutions should be compared.

So, I decided to challenge myself: This past semester I participated in an exchange program through which I spent the spring studying at the University of California, Berkeley. While I was enthusiastic about seeing and enjoying the Bay area, I was beyond nervous about how I would perform. Would I be able to keep up with the coursework? Will the readings be too dense for me? Will they expect me to know things that I don't? The answers to these questions haunted me as the plane landed in Oakland.

But, when the semester began, I quickly realized that I had psyched myself out. And, with the semester over, I can assuredly say that there was no significant difference in level of difficulty or quality of conversation in the classroom; I never once felt overwhelmed, exhausted, outperformed or underprepared. In fact, my grades improved during my semester at Cal -- the GPA I earned this semester is higher than any semester GPA I have earned at Morehouse over the past two-and-a-half years.

To be sure, the only aspect that I found more difficult was the racial climate. I found it difficult to live with a roommate who, within 20 seconds of meeting me, told me how interesting and controversial he thought Black people are because we "speak ebonics"; I found it difficult to walk down the street at night and to have a gang of drunk, rambunctious white boys drive speedily past me, call me the N-word, and tell me that I needed to go home; I found it difficult to share intellectual space with students who constantly circumvented analyses of race; and, I found it difficult to be told that being unflinchingly critical of racism and colonialism makes white people feel uncomfortable. Needless to say, the rest of the insecurity I once felt about my HBCU has melted. The feeling that once was now takes the form of anger and worry--I am angry about how humiliated I felt to have to attend Morehouse; I worry about Black high school seniors whose college selection processes are being muddled by college and university rankings and analyses that neglect their experiences.

I also worry about the consistent, unproductive rivalry that exists between Black students at PWIs and Black students at HBCUs. Recently, the students of Black Twitter debated ferociously after this tweet went viral: "A 4.0 at a [sic] HBCU is not equivalent to a 4.0 at a rigorous PWI. No shade being thrown, but that's the truth!" Students at both institutions seemed to have mixed feelings about the tweet -- some HBCU students scrambled to defend their institutions, and some agreed that their education wasn't up to par; some PWI students proudly agreed that their schools set the bar, and some stood in solidarity with HBCU students. However, the question itself -- Can HBCUs compare to PWIs? -- assumes the centrality of PWIs and distracts us from noticing and taking seriously the work that all schools need to do to improve. So, instead of creating and recreating a fictitious binary where HBCUs and PWIs are opposites on a single spectrum, let's start telling Black students the whole story so that we can make informed decisions about which schools we want to attend and what types of relationships we want to build across institutions.

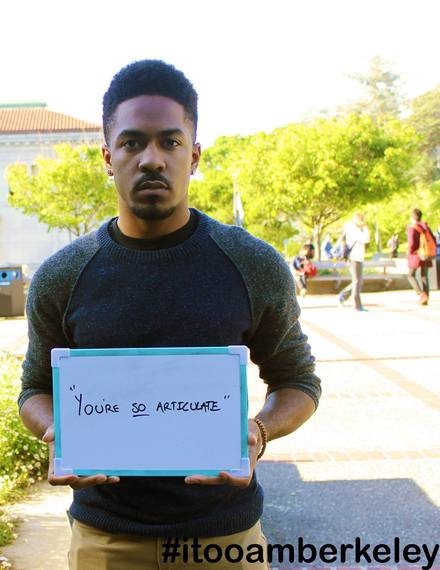

It is true that some people in the general public are unfamiliar with HBCUs; but, this truth isn't indicative of insignificance. It's indicative of anti-blackness in public knowledges -- people aren't familiar with North Carolina A&T because no one at any point in their intellectual journeys saw it fit to teach them about the Greensboro Four; people aren't familiar with Howard University because they've never critically studied a Toni Morrison novel or read a Stokely Carmichael essay; people know nothing about Rust College or Fisk University because they know nothing about Ida B. Wells. And, we have to deal with that. We have to deal with the fact that HBCUs find it harder to come by resources not because they aren't attractive or worthy intellectual spaces, but because, in a "post-racial" society, donors do not see the need for/value of institutions that specifically serve communities of Black students -- now that Obama's elections have somehow proven racism wrong, funding Black education is no longer in style. We have to deal with anti-Blackness at different institutions in different forms. As the "I, Too, Am [Berkeley/Harvard/Princeton/etc.]" campaigns suggest, we have to deal with anti-Blackness at PWIs in the form of racist micro-aggressions and race-neutral syllabi that imply that Black people have had nothing at all to say about a given topic.

At Morehouse, we have to deal with internalized anti-Blackness in the form of respectability politics -- like the sign on the window of the Morehouse Campus Police Department office which reads "PULL UP YOUR PANTS or Don't Come In!!!"

Here, Morehouse is reinforcing the myth of inherent Black male culpability and agrees with the set of conditions placed on respect for Black people. These are the states in which Black students in higher education find ourselves; and, unfortunately, we have to deal with it -- all of it -- as we select and attend colleges.

What I hope to impart is this: Every student has a set of experiences and goals that fit the personality of a specific institution. As Black students, we'll face challenges no matter what school we attend; but, mainstream sources and college pamphlets won't do the work of making those challenges plain. For that reason, it's crucial for us to be critical of what we are being told about different colleges and universities. To be clear, I do not mean to imply that HBCUs are the schools for all Black people or that any and every Black person at a PWI will feel the way I felt -- my Black friends at Cal love it and have found safe, critical spaces in which they discuss their experiences; and, with a dress code from the 1950s, surely Morehouse is not without its fair share of problems and would not be a home to everyone. However, when we make heavy handed generalizations about higher education, critical thought about our experiences gets lost and we miss opportunities to hold our institutions accountable to our needs. And, insofar as we aren't critical of the problematics of our experiences, we're pushed to normalize that which marginalizes us -- Black students at PWIs are pushed to conceive of syllabi complete with solely white thinkers as rigor and Black students at HBCUs are pushed to understand pearls and bowties as badges of honor. Instead, if we prefigure our own brilliance -- if we assume our own inherent potential and value as students and remain critical -- we can begin to see the challenges that seek to obstruct us more vividly, call them out more pointedly, and work together across institutions to create change more triumphantly.