Everybody loves a cute picture of a baby bird, which is why the Internet is packed with shots of these tiny balls of fluff, watched over by their adoring parents. Nature's reality, however, is a lot less adorable. Many wading birds—including egrets, herons, and storks—actually feed their babies to local alligators in exchange for protection from other predators.

A new study published in PLoS One explores the complicated relationship between colonies of wading birds and alligators in the Florida Everglades. Environmental scientists have known for a long time that birds and alligators thrive in part thanks to a mutually beneficial arrangement that's called "facilitation." The birds choose to nest in trees right at the center of dangerous alligator territories--and it's out of a sense of self-preservation. Their nests are out of chomping range, which means the local alligators focus on killing the raccoons and possums that would normally eat birds' eggs. Alligators keep the birds' nests safe from predators.

Rarely did anyone wonder what alligators got out of this deal. They can get raccoons anywhere, so why stick around bird colonies? Answering that question is the focus of this new study.

It turns out that there are two immediate benefits for alligators. One is an indirect benefit, because bird guano is full of nutrients which can make the region more attractive for marine life generally—and that can mean more tasty treats for the gators. The other is a direct benefit. Most wading birds tend to spawn far more chicks than they can fit in one nest. So adult birds toss extra chicks out into the swampy waters below for the alligators to enjoy. When you've got an entire egret colony, that's a lot of chicks.

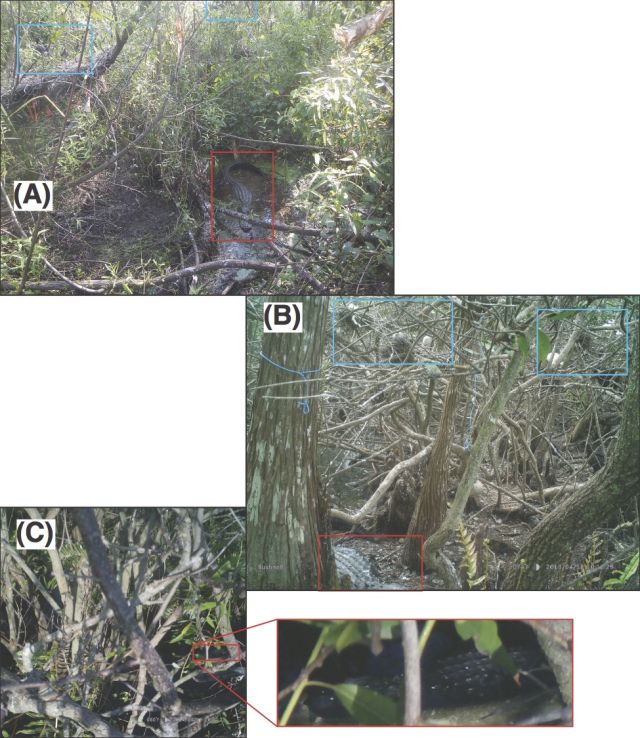

By placing cameras near birds' nests in swamps (see below), the researchers found that alligators frequently hang out directly under the nests within chick-catching range, clearly hoping for the adults to toss them a snack.

Sympathy for the alligator

The facilitation between birds and alligators is clearly a two-way street, but that raises the question of whether alligators who team up with wading birds are actually better survivors than those who don't. Do alligators get enough chicks out of the bargain that they are actually more fit to reproduce?

According to the researchers, the answer is yes. They found this out the hard way, catching and releasing alligators by hand in the Florida Everglades.

In a section of their article delightfully called “alligator sampling,” the researchers explain that they conducted their research near the semi-submerged islands where wading birds nest in freshwater swamps. During several summer nights in June of 2013 and 2014, they captured and examined 39 female alligators—20 from areas where they lived in facilitative relationships with egret and heron colonies and 19 from areas where they didn’t.

By measuring the alligators’ mass relative to their length, the researchers determined that alligators who lived near wading bird colonies were healthier, with higher relative body mass. Their body masses were similar to those of alligators who choose to reproduce. The alligators who weren't in facilitative relationships were less likely to have a body mass that would make them want to breed.

The researchers write:

The magnitude of benefits demonstrated here indicates that for alligators there should be selective pressure toward behaviors that enhance the benefits they derive from this association. We hypothesize that alligators are attracted to and, given their territorial behavior, may even compete for territories that include wading bird colonies.

Birds are, they add, are creating "localized nutritional subsidies" for the Florida alligators.

In the end, alligators are getting roughly the same benefit from the facilitation arrangement that the birds are. Alligators protect the bird eggs from raccoons; and the birds toss the alligators enough extra protein that they grow to breeding size more often than their counterparts. Seems like a nice arrangement, unless you happen to be one of those chicks who is too close to the edge of the nest.

PLoS One, 2016. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149572

reader comments

76