The Banality of White Nationalism

The existence of extremists like Tony Hovater doesn’t require extraordinary explanations—they stand in a long American tradition.

In 1963, Air Force Captain Ed Dwight was assigned as the deputy for flight test at the bomber test group at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base outside of Dayton, Ohio. Dwight was a hot-shot pilot—a recent graduate of the elite Aerospace Research Pilot School, recommended by an Air Force board for NASA’s astronaut training program. A Catholic publication put news of his arrival on its cover; a parishioner heard that Dwight was having trouble finding a nice home for his family, and rented him a house in the booming suburb of Huber Heights.

Dwight was black. Ebony reported what happened next:

Soon after the Dwights moved in, the harassment began. His auto took the most punishment: grease was smeared over the spark plugs, air was let out of tires, and at night the vehicle was pelted with rocks. Shouts of “niggers, go home!” met the family almost every day. Dwight finally decided to move after a brick was thrown through a window and his daughter, Tina, was showered with broken glass.

The New York Times reporter Richard Faussett recently sat down to dinner with Tony Hovater, and his wife, Maria, at an Applebee’s in Huber Heights. Faussett was struck by how ordinary Hovater seemed. “His Midwestern manners would please anyone’s mother,” he wrote, calling him “polite and low key.” They had turkey sandwiches at a Panera Bread. Faussett had come to Ohio, “amid the row crops and rolling hills, the Olive Gardens and Steak ’n Shakes,” to solve a riddle, as he later reflected: “Why did this man—intelligent, socially adroit and raised middle class amid the relatively well-integrated environments of United States military bases—gravitate toward the furthest extremes of American political discourse?”

Because Hovater, it turns out, is a white nationalist; as Faussett put it, he’s “the Nazi sympathizer next door.”

Huber Heights, now home to Panera and Applebee’s, sprang up almost overnight. There were just 1,900 residents in the township in 1950; Charles H. Huber began erecting neat red-brick ranch homes in 1956, and soon built 9,000. His houses offered a step up for those who had flocked to Dayton to find jobs in its wartime factories—affordable, single-family homes. White families moved out to the suburbs first, and most did their best to preclude black families from following.

Desegregation was an uneven process in the Dayton suburbs. Alan Arthur Anderson moved with his family into Huber Heights in 1963, the same year as the Dwights, but local ministers spent two weeks clearing the way for their arrival. The county sheriff told The Cincinnati Enquirer that “neighbors brought cakes, cookies, candies and good wishes.” But down the road in Townview, the Fuller family was met with up to 500 protestors, including some wearing white sheets; the sheriff had to invoke the riot act and send in 100 police to break up the protest.

That legacy lingers to the present. The Urban Institute ranks Dayton as the 14th most segregated city among the largest 100 American commuting zones. There are, according to the Census, just 28 black residents among Hovater’s nearly six thousand neighbors in New Carlisle.

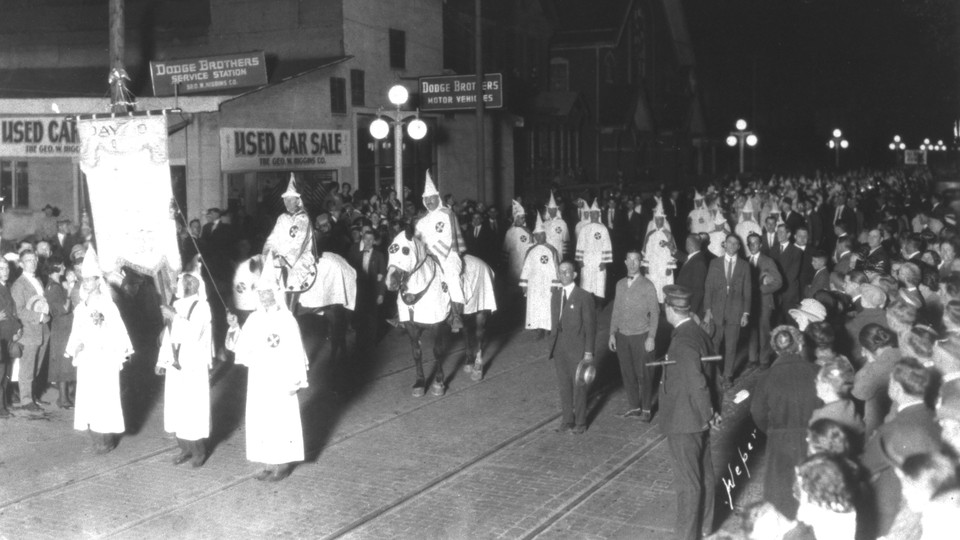

There were racist displays in Dayton before and after the battles over desegregation. The Second Klan, which flourished in the 1920s, flourished in the area. In 1923, Klansmen paraded four abreast through the streets, the winding column taking 45 minutes to pass by onlookers. One Dayton member of the Night Riders, the Klan’s activist arm, described its purpose as “horse-whipping, tar and feathering, barn burning, bombing—a regular reign of terror.” In 1966, Lester Mitchell was sweeping the sidewalk in front of his house in West Dayton at 3 a.m., when witnesses said three white men drove past, delivering a fatal shotgun blast to his face. Rioting ensued. And in 1994, 11 Knights of the Ku Klux Klan staged a rally in downtown Dayton to recruit new members.

The point isn’t that the Dayton area is some exceptional hotbed of American racism. It’s that it’s a very American city—embodying the nation’s complicated and contradictory history. It’s been home to radical abolitionists and to pro-slavery rioters; to black entrepreneurs and to white segregationists; to civil-rights heroes and to white-sheeted Klansmen. This was true long before the creation of 4chan or the white nationalist rally in Charlottesville; they are not needed to explain it.

Faussett went to Ohio, he wrote, determined to find Hovater’s “Rosebud,” the extraordinary, radicalizing experience that set him on a path to extremism. His reporting contrasts the “quotidian” details of Hovater’s life with the virulence of his beliefs. Ultimately, he conceded, “there is a hole at the heart of my story,” which “would have to serve as both feature and defect,” the inability to explain a white nationalist growing out of an ordinary suburban landscape.

But if Faussett was asking the right question, he may have been looking in the wrong places for answers. Faussett was looking for a radical disjuncture to explain Hovater. But the disjuncture in America’s history is not the emergence of virulent racism, it’s the uneven, often halting progress the nation has made toward greater equality, enlarged tolerance, and defensible rights. It’s a complicated story. It requires understanding what made a man like Dwight hold the nation to its articulated ideals, despite the risks. Or what made a man like Fuller, a mason who laid the bricks for many of his neighbor’s homes, insist that he, too, had the right to live in such a house.

The Hovaters of Ohio, though, are perhaps less mysterious. Ed Dwight would not have been surprised to meet Hovater. Neither would the Fullers, nor the Mitchells, nor the hundreds who rallied against the Klan in downtown Dayton in 1994. They’re a vestige of a long tradition—as American as Applebee’s.