Facebook just acquired an obscure company in India with this sole purpose in mind: Encouraging data-poor people—or in other words, most of its customers in emerging markets—to spend as much time on Facebook as possible by removing the infrastructural barriers to hanging out online. The company, Little Eye Labs, makes tools that help Android app-makers monitor and improve the performance of their apps by keeping an eye on how much data, power, memory and disk space the apps are using. It can be immensely useful for developers trying to make their apps as lightweight and easy on the system as possible, and it was acquired to do the same for Facebook’s own Android apps, according to a Facebook spokesperson.

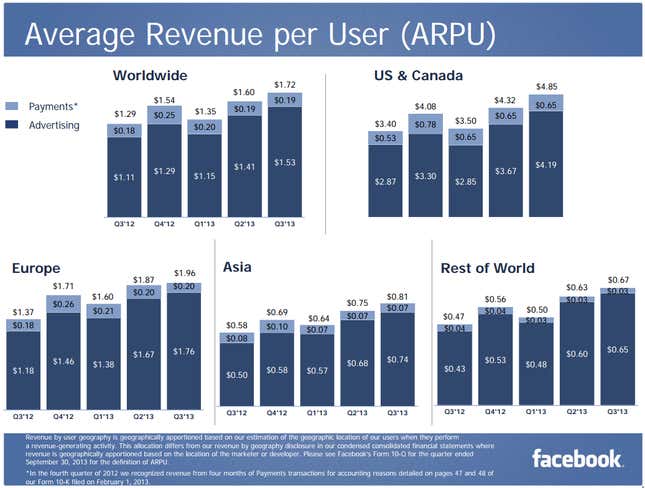

But getting people to spend time on Facebook is just the beginning. As in the West, Facebook spent years growing its user base before it figured out how to properly make money from it. That’s why the 60% of Facebook’s users who live outside North America and Europe contribute just 25% of its revenues. Little EyeLabs is part of the effort to change that equation.

The big challenge ahead

India, along with Brazil, is high up on Facebook’s list of priorities. The two countries regularly trade places as Facebook’s second- and third-largest user base (after the US). Facebook has had some early successes in Asia and Latin America, where the majority of smartphones will be sold this year. Its revenue in those regions is are ticking up (pdf), but slowly. To speed it up, Facebook needs to address a fundamental problem that at this point it can do little about: measuring advertising impact.

Facebook, like any company that sells ad space, eventually needs to show advertisers that they are getting something for their money; that the ads are actually swaying the people viewing them. This is easier for a company like Google. Ads next to transactional search terms, such as “refrigerator,” are successful because people are often searching for these things with the intent of buying them. People don’t go to Facebook to buy things, so ads on the social network tend to be aimed more at creating awareness about a brand or running campaigns.

In the US, Facebook measures the effectiveness of ads on its network with something called Nielsen OCR, which generates ratings that the company says are comparable to those used for television. Nielsen does this by combining anonymized, aggregate data from a variety of sources, such as supermarket loyalty cards and Facebook itself. Such systems, and indeed such data sets, do not exist in the developing world. It is something Facebook takes seriously.

“That is a very big issue for us,” Brad Smallwood, Facebook’s vice-president of measurement, told Quartz in a December interview. “We generally don’t love using panels but we’re starting to use more and more panels. In the absence of data assets we work with the advertisers to say what are you doing today, what can we do to help with the process, and what data can we contribute into these systems? It’s not a great answer and from my perspective, it is the biggest growth area that we’re working on [in 2014].”

Laying the groundwork

In a way, Little Eye Labs is the flip side of Facebook’s other recent high-profile acquisition, Israeli start-up Onavo, which helps individuals reduce the load on their mobile internet by crunching data before delivering it to the phone. That speeds things up and brings bills down. Both are designed to make Facebook take up less of the expensive, slow mobile bandwidth available in emerging markets. That is, after all, why Mark Zuckerberg started internet.org, a consortium of companies “working together to bring the internet to the two-thirds of the world’s population that doesn’t have it.”

What such acquisitions share in common with the issue of measurement is that in both cases, Facebook needs to build the infrastructure to expand its user base and profits overseas. Getting users to stay on Facebook so it can show them ads is the first step. Figuring out whether they’re actually looking at them is much harder.