The stories are of unspeakable cruelty.

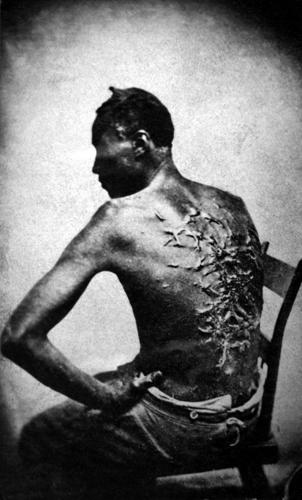

“I was severely punished by a board cut full of holes to raise the blisters, then I was whipped with a strap to burst the blisters, which were then salted and peppered,” Thomas Brown said. "This burned me very badly.”

The South Carolina slave had escaped and hidden in nearby woods but had been found by bloodhounds and brought back.

"And I never tried to run away again.”

His very words. His story.

Brown's powerful telling of his treatment as a slave, along with that of more than 200 other former slaves, can be found online because of the work of John B. Cade Sr. and Southern University.

Slaves at Rosedown Plantation, the state’s most visited historical site, were “happy” and had “a natural musical instinct,” claimed the wordin…

When Cade was on the faculties of two historically black universities in the first half of the 20th century, he sent students to collect stories from former slaves. The narratives are in the Southern University library that is in Cade's name.

For all practical purposes, though, the stories could have been locked in a vault.

“The collection has been sitting in the library for years, and no one attempted to do anything about it,” said Angela V. Proctor, university archivist and digital librarian at the John B. Cade Library.

That changed three years ago when Southern posted the narratives online. Now, anyone with internet access can read what the slaves had to say.

That's prompted calls to Proctor from researchers in several countries interested in learning what former American slaves said about their lives.

Cade began collecting the stories after he arrived at Southern in 1929 as registrar and as principal at Southern University Lab School. He continued while on the faculty at Prairie View A&M from 1931-39 and after returning to Southern in 1939 as dean and director of extension services, Proctor said. Cade retired in 1961 and died in 1970. The collection at Southern includes interviews Cade collected while at Prairie View, Proctor said.

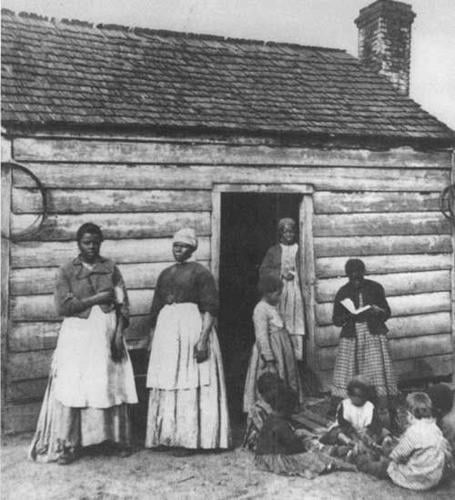

Common themes from the narratives in the Southern University archives are that most slaves lived in simple, dirt-floor cabins, wore homespun clothing and were forced to work hard — especially field slaves.

A group of slaves stand outside a typical slave cabin.

Part of Cade’s motivation was to counter white historians’ suggestions that slaves had not minded their status, Proctor said. Few narratives in Southern’s collection support the idea that slavery was a benign institution.

Cruelty, particularly from the overseers hired to manage slaves, is a frequent theme.

South Carolina slave Louis Bishop said that to maximize productivity, punishment for infractions would be delayed until rainy days, when the slaves wouldn’t be working.

“My master was so cruel to his slaves that they were almost crazy at times,” said Bill Collins, an Alabama slave born in 1846. “He would buckle us across a log and whip us until we were unable to walk for three days. On Sunday, we would go to the barn and pray to God to fix some way for us to be freed from our mean masters.”

The slaves made clear they had virtually no control over the most basic decisions. They needed permission to marry, a permission that some owners declined to give. In some cases, owners decided which slaves could wed and to whom. It was common for families to be broken up as some members were sold to other owners.

“My mother was sold away from me,” said Collins. “I was so lonesome without her that I would often go about my work and cry and look for her return, as I was told by some of the slaves that she would be brought back to me, but she never came back.”

In grade school, many Americans learn about the Underground Railroad, a clandestine network that helped Southern slaves escape to freedom else…

Jourden Luper, born in Charleston, South Carolina, ended up in Texas with no memory of a mother or father, who were sold separately before he turned 2, his grandmother told him.

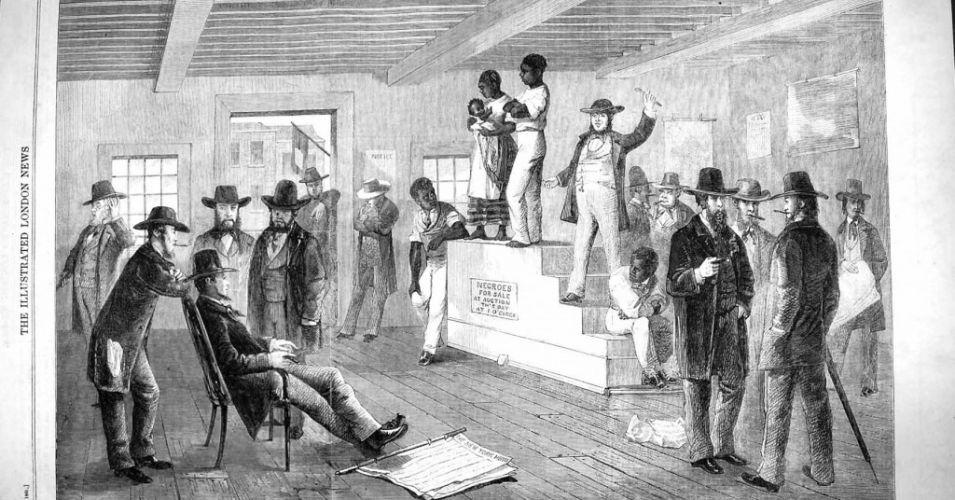

“The worst thing about slavery was selling the slaves on the auction block like they were cattle,” said William Haynes, a Virginia-born slave who was moved to Texas.

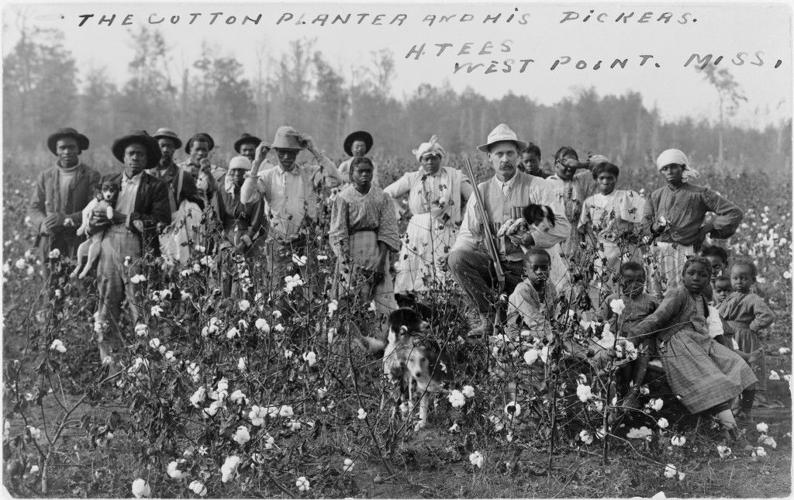

Common themes from the narratives are that most slaves lived in simple, dirt-floor cabins, wore homespun clothing and were forced to work hard — especially field slaves. They would rise well before dawn, eat, feed and milk cows, then report to the fields so they could begin work as soon as it was light enough to see.

“The women, as well as the men, had to work in the fields chopping and picking cotton," Haynes said. "The only pay was a whipping."

Some masters forbade any religious practice, forcing slaves to sneak into the woods to pray and sing or risk being caught in their quarters. Other masters took slaves with them to church.

“They would pray saying, ‘O Lord, lift the yoke of bondage of us that we may serve God under our own vine and fig tree. And, O Lord, control Ole Master’s temper so he will not be so mean to us,’” wrote Esther Lane-Thompson of her interview with Mark Slater, an Alabama-born slave who was taken to Washington County, Texas.

Word of emancipation arrived, with tragic results for a slave named Klora, who was told of it by a white boy.

Klora’s master saw her talking to the boy and asked if he’d said anything about emancipation. She denied it.

“Then, her master tied her across a barrel and whipped her until she died,” said Luper, the South Carolina slave who ended up in Texas. “The master’s girls begged for Klora, but it did no good. He then whipped the boy until he died. The white boy’s mother cried and begged for her son’s life, but it did no good. That was a very miserable crime.”

Slaves who had kind masters celebrated their emancipation.

“We were not cruelly treated,” said Jake Delaney. “But after freedom, I could see that slavery was the worst thing that a race could experience.”

Southern University slave narratives

- Visit the John B. Cade Library website at lib.subr.edu.

- Click on the Slaves Narratives Collection icon.

- Click on the "Opinions Regarding Slavery: Slave Narratives" link.

- Narratives are grouped by the state, territory or nation of birth, with links to each grouping in the left column of the page.