Home Office efforts to launch a phone app for EU nationals registering to stay in Britain have been dealt a blow after complaints that the passport recognition function does not work on all phones.

Universities participating in a trial of the app have resorted to buying a supply of phones that do work as has one law firm advising applicants.

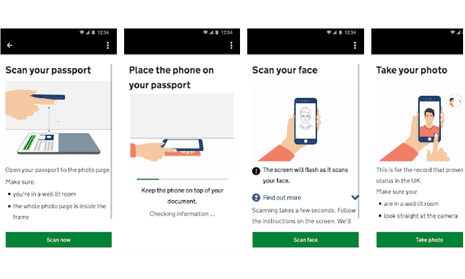

Earlier this year the government admitted that the app, which is supposed to enable applicants to complete a necessary ID verification check, did not work on iPhones.

But months after the former home secretary Amber Rudd claimed that applying for “settled status” would be as easy as online shopping at LK Bennett, a string of bugs have been reported in the app, EU Exit.

Concerns have also been raised that the Home Office requires users to allow it to share data with other public and private organisations at home and overseas.

Since a limited trial began on 1 November, users have reported that the passport chip scanner does not work on certain phones and the app does not appear to work abroad. There are also backend problems at the Home Office, with one user reporting that the government had emailed to say the were unable to find records of residency documents they had issued to a Dutch family.

“They’ve basically put out an app that isn’t ready to put into beta testing, never mind ready for Brexit,” said one German national, who lectures in medieval history at Bristol University.

He said the passport chip scanner was frozen for seven days after every failed attempt and described the Home Office customer service offered as “useless”.

“Everything they suggest does not work, including using a friend’s phone. The problem is that once you start the scanning process on one phone, the system remembers your passport number and freezes the process and doesn’t seem to allow you continue,” said the 33-year-old, who asked not to be named.

The academic was told by officials he could take his passport to one of 13 centres around the country that can perform document authentication reports but objected to having to pay £14 and the train fare to Bath to get around a tech failure.

His story was echoed by other frustrated applicants.

“Doesn’t read chip. I have pure Android: Umidigi Pro 1 with NFC and nothing. Now I am locked for 7 days. How can I avoid a wait?” said Pawel Janeczek on the Google Play store review page.

Another, Stavros Velissaris, said: “Same here! App does not recognise passport document.”

“Just doesn’t work… Doesn’t read the passport chip. Get it together or create different app!” wrote Weronika Czyniewska.

Esyllt Martin, an immigration lawyer with Eversheds-Sutherland, who is advising four universities in the trial said the chip scanner was “the biggest glitch”.

“It requires you to practice to be able to do it which is not ideal as the pilot is so short,” she said.

She confirmed that two of the four universities and her own companies had bought a set of up-to-date smart phones to lend out to applicants whose own phones didn’t work.

She said she had helped more than 100 applicants. “Mostly when they come to me, they were feeling very nervous. I have seen most of the glitches but have been surprised at how easy and fast the app is.”

Another German national at Bristol University reported that the app did not work overseas. He was on study leave and is frustrated because he will not get back to Britain before the trial closes on 21 December.

“So it doesn’t work for people who are still exercising their freedom of movement rights,” said Julio Decker, who lectures in North American history.

A researcher at Leeds University, which is also taking part in the trial, said he filled in the application on the phone app successfully, but the Home Office came back to say it could not find any evidence of his or his wife and children’s residency documents on its system.

“My experience of the app was not too bad,” said Robin Bon, a chemical biologist and Dutch national. “It has some teething problems, but it is problematic if they can’t find their own documents they issued to us.”

How can it be that the @ukhomeoffice has no proof documents that they have issued to us themselves? How many people are at risk if this is a more wide-spread problem. Hasn't @guardian exposed enough flaws of the @ukhomeoffice yet?

— Robin Bon (@RSBon_Lab) December 5, 2018

The Home Office admitted that there were still bugs in the app and the point of the beta trial was to identify and fix them before the app goes live nationwide at the end of March.

“The ongoing private test phase of the EU Settlement Scheme is providing us with vital and welcome feedback on the functionality of the system, including the beta version of the app, to help us make any necessary changes before the scheme is opened fully by 30 March 2019,” a spokesperson said.

“So far, the overwhelming majority of those starting applications on the app have completed them successfully.”

Others have already told the Guardian that they are unhappy with passing on their personal data.

Another applicant, Alexandrine Kantor, questioned why the Home Office said it might share data with private or overseas organisations.

“It’s enough to create fake passport or to sold us out to nasty insurance companies. But why overseas? Who and what is it for? I cannot apply until this is not explained, this is my right. Is it even GDPR compliant?” she asked.

Another Dutch national said he decided to join the pilot so he had evidence in future years in case of any Windrush-type scandal.

“The settled status has made me feel very unsettled. It is like any wrong move can lead to deportation,” he said.

The trial, open to 250,000 people, will raise important issues for the Home Office’s plans to reach the estimated 3.5 million EU nationals, some of whom may not be tech-savvy or may be reluctant to share data over a phone.