An original copy of the Irish proclamation of independence that was posted on the wall of Dublin’s general post office (GPO) in 1916 is going on full display for the first time.

The document forms the centrepiece of a new exhibition at Trinity College Dublin commemorating the centenary of the Easter rising against British rule, which began when the proclamation was read out by rebellion leader Patrick Pearse outside the post office, where the rebels were headquartered.

This fragile piece of paper is as important to Irish nationalists as an original copy of the US constitution is to Americans. To underline its significance, the government will hold a “proclamation day” on 15 March, when 2,300 schools will be given copies and the Irish tricolour will fly from school buildings. In an ironic twist of history, Trinity College, founded by Queen Elizabeth I, was an important base for the British armed forces sent to quell the rising. Trinity students’ Officer Training Corps (OTC) sealed off the university and prevented it from being taken over.

Many Dublin families had men fighting the Germans on the first world war’s western front, and the insurgents appeared not to have popular support. Six days after it began, the revolt was put down by the British.

However, the execution of the rebel leaders and the imposition of military conscription in 1918 swung nationalist public opinion in favour of the rebels’ radical republicanism, sparking a national war of independence. That conflict ended with Ireland being partitioned into two states in 1922.When rebels in the post office surrendered after a relentless artillery bombardment, the proclamation was stripped off the wall by Major Louis Tamworth, a British army officer, as a war souvenir.

Tamworth took it back to England, where it remained with his family until 1970, when it was acquired by Trinity. Historians and researchers have had access to the document but until now it has not been displayed publicly.

In 1977, archivists at the university discovered that the proclamation had been pasted on top of other posters. “It emerged that the rebel who pasted up the proclamation inside the GPO’s walls posted it on top of 12 British army war recruitment posters, which were designed to boost Irish numbers in the British military,” says Shane Mawe, assistant librarian in charge of posters and publications at Trinity.

“Peeling back the proclamation reveals the complexity of Ireland at the time, as tens of thousands of Irishmen were fighting in British regiments.

“Our copy of the proclamation is pretty much unique because of its interesting provenance. The plan was originally to distribute 2,500 copies across the country, but only about 1,000 actually were printed. There are fewer than 50 in circulation today. On the walls of the GPO there were only three.”

By pasting the proclamation over the recruitment poster, the rebels were “sending out a new political statement,” Mawe says. “It is denouncing joining the war effort and pronouncing the new republic. The proclamation and the posters it replaced tell the story of the journey from recruitment to the republic.”

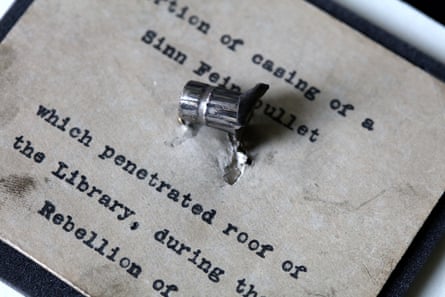

Trinity is also exhibiting the casing of an Irish rebel bullet that struck the university library as insurgent snipers fired at the OTC and British troops. The remains are mounted on a mini plinth with the words “Sinn Féin bullet” engraved on it.

Estelle Gittins, assistant librarian for manuscripts and archives at Trinity, describes the artefact as a tiny monument to the college’s role in the rising.“It’s incredible to think this was a bullet fired into the place where we now work, and a reminder about how extremely violent and dangerous it was in this college 100 years ago.”

The original GPO proclamation and spent bullet round can be seen digitally on the Trinity College blog marking the the centenary of the Easter rising.