Of all the running gags on the recently ended How I Met Your Mother, Barney Stinson’s catchphrase—”It’s gonna be legen—wait for it—dary“—was perhaps the most satisfying. It captured the bro-y, over-the-top essence of Barney, a womanizing metrosexual and frequent high-fiver played by Neil Patrick Harris, whose character famously ushered out Season 2 of the series with a dangling “wait for it …” and made us wait all summer long until Season 3, which opened with “dary.” The phrase spawned self-referential meta-jokes on occasion, and headline writers predictably played with it when bidding the show farewell two weeks ago.

But “legen—wait for it—dary” also represents an issue of decidedly un-bro-y complexity in the world of linguistics. It’s an example of tmesis, a phenomenon in which one word or phrase splits another, often for emphasis. You may remember Matt Foley, the in-your-face motivational speaker played by the late comedian Chris Farley on Saturday Night Live, whose “Well, la-dee-frickin’-da” was all the funnier for its tmesis.

All of which raises a question that linguists have yet to fully resolve. How do we know where to inject the interrupting word? Or, to put it another way, why does “le—wait for it—gendary” sound so wrong?

First off, the term tmesis derives from the ancient Greek word for “I cut,” and the device has been around for millennia. Puzzle-minded Romans sometimes used it in rebus-like wordplay. A particularly gruesome example comes from Quintus Ennius, a poet of the 2nd century BCE, who depicted a character’s death by inserting the word for “he broke it [with a rock]” into the word for “head” (“saxo cere comminuit brum“). Clever.

Tmesis is a variety of what linguists call infixation, a catchall term for when extra syllables are added in the middle of a word. This occurs regularly, for instance, in the poems of another celebrated, though more contemporary, writer: Snoop Dogg. His modification of words with the syllable “izz” (as in “You can leave your worries behizzind/But I’ma get back to the grizzind“) popularized a form of slang that Bay Area rappers had been using for years. Mark Lindsay, a Ph.D. candidate in linguistics at Stony Brook University, suggests that iz-infixation “may be used for obscuring profanity (e.g., ‘dizamn’ for ‘damn’) or expressing ‘a hint of joviality’ (e.g., ‘Whassup in da hizzouse?’).”

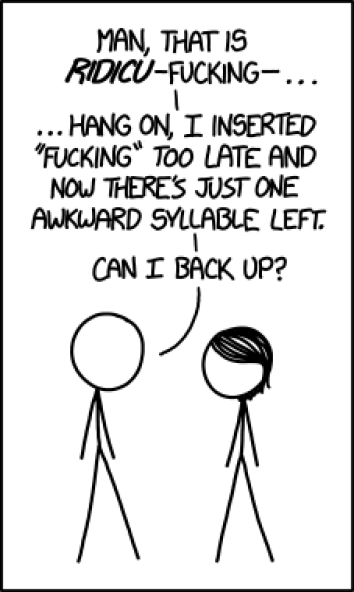

It’s probable that neither Stinson nor Dogg had to think very hard about their respective infixes, but attempt to articulate a single rule that governs both and their use of language suddenly seems sophisticated. The popular webcomic xkcd made a joke of the unlikelihood that English speakers would be confused about where to put an infix. That we know instinctively. The hard part is explaining how we know.

xkcd.com

The simplest theory of infixation in English says that the addition naturally comes just before the most heavily stressed syllable. That’s an okay rule of thumb. It works for “legen—wait for it—dary” and plenty of other examples, like Luke Wilson’s response to having his arms ripped off by a bear in Anchorman (“ri-goddamn-diculous“). It excludes many other infixes, however, including iz, which typically wriggles in just before the first stressed vowel.

University of Chicago linguistics professor Alan Yu has a more comprehensive theory. According to his book A Natural History of Infixation, infixes appear either near the edge of a word’s stem or next to a stressed unit. That includes locations from the first consonant to the final vowel, and proves no more helpful in predicting where the split will fall in any given word.

However elusive, it’s important to try figure out the rules of infixation, says Yu, because the fact that it exists at all seems to challenge what we know about how people comprehend language. Infixes interrupt a word’s structure far more than prefixes or suffixes do, so they should be relatively difficult to process. It’s therefore surprising that infixes have continued to emerge throughout history.

In some cases, of course, discouraging comprehension is precisely the point. Two decades before Snoop Dogg popularized iz-infixation, the spoken-word artist Gil Scott-Heron performed “The Ghetto Code,” which included these lines about outsmarting a wiretapper:

Old-fashioned Ghetto codes saw phone conversations like this:

“Hey, Bree-is-other Me-is-an!

You goin’ to the pee-is-arty to-nee-is-ight’ Oh yeah!

Well, why not bring me a nee-is-ickel bee-is-ag, you dig’

And some Bee-is-am-bee-is-oo to ree-is-oll it up in!”

I know whoever they was payin’ at the time to listen in

on my calls had to be scratchin’ his head, sayin’

“Dot-dot-dit-dit-dot-dot-dash” (Damn if I know!)

The entertaining quality of Barney Stinson’s “legen—wait for it—dary,” I’d argue, is likely related to its very comprehensibility. Barney thinks he’s keeping his listeners in suspense by forcing them to wait for the end of the phrase. But after hearing it once, the audience, both the characters in the show and the viewers at home, knows what’s coming. The fact that Barney keeps saying it exposes his utter lack of self-awareness. His infixation fixation has transformed into something even more useful, a way for the show’s writers to make Barney the repeated punchline of his own ongoing joke. Which, if you think about it, is hi-freaking-larious.