Ramez Naam spends much of his time thinking about the future. But recently, the Singularity University lecturer—and one of the early architects behind Internet Explorer, Outlook, and Bing—has shifted his attention away from how people navigate cyberspace to the grimmer question of whether our planet can keep up with the future. Peering through a prism of technology, he wonders how the world’s resources will be able to keep pace with its population growth.

Naam is quick to note that he’s not the first person to probe the question. In 1798, Thomas Malthus, the forefather of population scares, issued humanity’s first warning that dire consequences awaited should the earth’s population continue growing unabated. Much later, in the 1960s, a new generation of Malthusians published best-selling books heralding mass famines if we didn’t prevent the explosion of what they dubbed “the population bomb.”

Malthusians new and old fear that agricultural production simply can’t grow fast enough to feed the ever-rising number of people on the planet. But to date, they have simply never been right—while famines do happen, it’s not because the world can’t produce enough food—and Naam is also quick to point out that he’s no Malthusian. “Whenever the need has been great, or the financial rewards high, inventors come calling,” Naam wrote in his 2013 book, “The Infinite Resource: The Power of Ideas on a Finite Planet.”

Today, Naam and the Malthusians can agree on this: The need for innovation has never been greater. By 2050, according to the World Resources Institute, we’ll have to find ways to grow food production by 70 percent to meet the needs of an estimated global population of 10 billion people.

But beyond overall population growth, there will be another 2.9 billion people joining the global middle class by 2030, according to a 2012 report from Reuters. Led by China and India, these fast-developing countries are providing their citizens with better education, more skilled jobs, higher incomes, and rapid urbanization. As they seek out a more prosperous middle-class life, similar to those in developed countries, they’ll disproportionately drive up the world’s demand for food, water, and energy, stretching thin some of the world’s already limited resources.

“Though it will take a while for the world to reach this level of affluence,” Naam says, “it is a foot race.”

Just as our hunter-gatherer ancestors evolved into farmers 12,000 years ago, today’s farmers are quietly undergoing a distinctly 21st-century transformation.

“It used to be, if you could turn a wrench you’d be good at farming,” Ernie Burbrink, a farmer at Tom Farms in Leesburg, Ind., told the New York Times in December. “Now you need to know screen navigation, and pinpointing what data should go where so people can plan and predict.”

While the dramatic innovations in farming practices in the 20th century saw crop yields skyrocket and still continue to move the dial, digital technologies are ushering in a paradigm shift on the farm. “I’m hooked on a drug of information and productivity,” Kip Tom, the seventh generation family farmer who owns Tom Farms, told the Times. “We’ve got sensors on the combine, GPS data from satellites, cellular modems on self-driving tractors, apps for irrigation on iPhones.”

What Tom is describing is an early form of the Internet of Everything—the idea that all things will be connected to the Internet through sensors that communicate with one another, analyzing and acting on the data they gather, with or without human interaction. It’s a technological ecosystem that’s being rapidly embraced by the agriculture industry for everything from crop productivity to pest control to—perhaps most urgently—irrigation.

Because crops require water and feeding a planet requires a massive amount of crops, irrigation is responsible for using 70 percent of the available freshwater in the world, according to Naam. Unfortunately, running parallel to the Malthusian fear of food scarcity is the very real threat that the world is running out of water; more than a billion people around the world lack access to clean water—not to mention the historic droughts taking place in California.

Over the past four decades, Australia, with its majority desert climate, has spearheaded efforts to use water more efficiently in agriculture, cutting the amount of water needed to grow a bushel of grain by a factor of three. Much of that has been focused on how the water is deployed, such as moving from flooding a field to spray irrigation to drip irrigation, an incremental and ongoing dedication to increasing precision. Now, with the emergence of the Internet of Everything, smart technology pioneered by Silicon Valley startups has the potential to revolutionize irrigation, taking that precision to unprecedented heights.

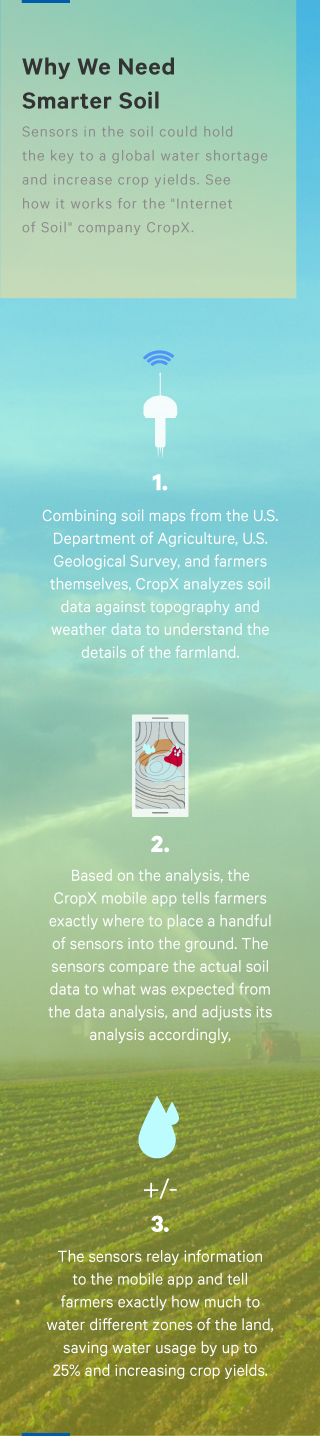

“At the moment, there’s a huge, glaring omission within the whole of agriculture,” says Isaac Bentwich, founder of agriculture analytics startup CropX, in an article in TechCrunch. “Virtually all agriculture systems irrigate land uniformly. Even the most advanced technology always treats land as though it were uniform.”

But because land can be different, even across a small plot, CropX has built what Bentwich calls “the Internet of Soil.” The company uses sensors placed in a field’s soil to analyze the land and, through a mobile app, tell farmers how much water to use to maximize the harvest across each portion of the farm. According to Bentwich, farmers using CropX have been able to achieve water savings of 25 percent—a huge number, especially considering a recent USDA survey that found just 10 percent of farmers use any tool to optimize their irrigation.

In the coming years, barring Malthusian catastrophe, that will have to change. Today, the average person in India and China consumes just 40 percent and 28 percent, respectively, of the amount of water consumed by the average American. In the coming decades, as billions of people in those countries climb into the middle class, they’ll expect the 24-hour access to tap water that Americans take for granted and will consume more foods that require more water to produce. Billions more still in poverty will continue to clamor for even moderate access to clean water.

Faced with such unprecedented stress on a water supply that can’t be expanded, even Bentwich, the exact type of the inventor Naam expects to defy the odds, can see where the Malthusians are coming from. “Agriculture has undergone three major revolutions in the past 150 years,” he says. “Each one assumed that water was limitless—water was always used to grow more out of every acre. Now, water has literally run out.”

Like Ramez Naam, Stefan Heck and Matt Rogers, authors of the recent book “Resource Revolution,” are optimistic. “The challenges we face may be unprecedented,” they write, “but, simply put, any bet that we will succumb to a global economic crisis is a bet against human ingenuity. No such bet has ever paid off.”

That ingenuity, as seen in CropX’s work in agriculture, is already beginning to play out across various sectors, offering clues for how the technology may trickle through the economy to validate the authors’ faith that innovation can prevent a global famine.

Consider OPower, an energy company working to make energy use more efficient in a world that still depends on high-pollution fossil fuels. The company recognized that the massive amount of energy used by Americans on heating and cooling was being inefficiently tracked, so it began collecting real-time data from energy meters in people’s homes. In doing so, it essentially turned regular meters into smart meters—creating an Internet of Energy not unlike CropX’s Internet of Soil. OPower sends its customers a report on their energy usage, using data to understand when they were and were not home and how efficient their energy use was. It lets customers see how they compare to their neighbors and whether they’ve been particularly wasteful.

Studies have shown that by using OPower’s service, people can reduce their energy usage by 2 percent. As modest as that sounds, if everyone in the U.S. were able to drop their energy usage by 2 percent, it would free up the use of the equivalent of 130 power plants, according to Heck and Rogers.

Meanwhile, there’s also Waze, a crowdsourced, real-time GPS and traffic navigation app bought by Google for $1.3 billion in 2013. Waze capitalizes on the sensors in its millions of users’ smartphones to effectively create an Internet of Traffic. By tapping into its user base of drivers, it collects their GPS locations and determines which cars are moving, where they’re going, and how fast they’re traveling, automatically providing the best route from point A to point B given real-time traffic and road conditions.

Perhaps more than any other app today, Waze has “illustrated the promise of the ‘Iinternet of Tthings,’ showing how a vast network of connected devices can make life easier,” according to Quartz’s David Yanofsky, using another common phrase for the Internet of Everything.

How Do You Build a Sustainable City?

Chip by Chip

Every streetlight, trash can,

and sewer cap will soon be

as smart as your smartphone.

In May 2013, an article in the Harvard Business Review described a clash in progress between the old, physical economy and the new, digital one.

The old would soon be forced to evolve and adopt the new by building software into almost every kind of product—or else be left behind.The piece was titled “How the Internet of Things Changes Everything.”

Two years later, it’s not easy to look around as a consumer and confidently say things look that much different than they did in 2013. While there have been more “‘things”’ connected to the Internet than people since at least 2008, 87 percent of consumers still haven’t heard of the Internet of Everything (IoE), which is also known as the Internet of Things (IoT).

None of this, however, means the hype was misplaced. Perhaps the changes are just less splashy than anticipated. Slowly but surely, technology companies are forming partnerships that are bringing the IoT to our daily lives in behind-the-scenes ways we may not even realize.

Qualcomm, for example, sees this new technology ecosystem as a way to manage the growth of cities by refreshing decades-old urban infrastructure for the digital age. While 70 percent of the world’s population are expected to live in cities by 2050, the infrastructures of most of them haven’t been updated in decades.

These forcasts “basically reflect the fact that now city managers, city workers, and municipalities are going to have to do more with less,” said Kiva Allgood, vice president of Global Market Development at Qualcomm. “Our goal is to help municipalities and cities really think about transformation of not only city infrastructure, but also how they plan for a long-term and more sustainable future.”

In this case, sustainability means using the Internet of Everything to create smart cities that are more efficient and less wasteful. As high-powered sensors have continued to become cheaper and more powerful, it’s now becoming possible to transform anything into a smart, data-driven device that cities can mine for insights—from trash collection routes to pollution to water usage.

With IoE, Qualcomm wants to do for municipal infrastructure what it’s done for the smartphone, which Allgood describes as a similar kind of “distributed network.”

“That’s what we do every single day when we connect millions of people’s cellphones,” she said. “They stay on the phone and somebody can watch YouTube and we’re able to manage and plan outbursts of [data] capacity, which works kind of like a city: People commute in the morning to work and then they leave in the evening. We understand that space really well.”

So when the City of Cincinnati looked for partners to deal with its water management issues—waste, changing consumer habits, and sewer overflows—Qualcomm partnered with the water experts at CH2M to collaborate on a solution. Together they mapped out the flow of water from source to tap, identifying pain points and challenges, before figuring out where in the process integrating IoE could make sense . Ultimately, they installed a smart network of sensors on pumps and sewage caps, all feeding real-time data to Greater Cincinnati Water Works.

“You can’t send somebody out there every 15 minutes or every 15 seconds to get the health of each pump,” Allgood says. “It’s almost as if we have another employee sitting on every single sewage line or pump station throughout the water process.”

With municipalities across America losing about 30 percent of their water from source to tap, the partnership is being watched closely. “The technology being implemented by Cincinnati will serve as a model for other U.S. utilities,” said Ken Thompson, CH2M’s Intelligent Water Solutions director.

But these kinds of IoE efficiencies go far beyond water.

With little fanfare, the business of trash collection is in the process of being radically disrupted. Bigbelly, a Wi-Fi-enabled trash- and recycling-bin company, has emerged on streets in Philadelphia, New York City, and other cities over the past several years. People dispose of their garbage in them as they would any in trash can, but inside, a Qualcomm Gobi 3G modem with GPS—the same chip that’s in millions of smartphones—gives them intelligence, saving a city millions of dollars and countless miles driven by garbage trucks.

By measuring the contents of the bins, the sensors communicate to maintenance crews which cans around the city need emptying and which don’t. In Philadelphia, Bigbelly has reduced collections by more than 70 percent. Meanwhile, in New York, the trash cans now double as Wi-Fi hot spots in areas with underserved Internet access.

In those trash cans, the connected-everything future predicted in the 2013 Harvard Business Review is coming to fruition. And Allgood says her team encourages municipalities to think about every piece of public infrastructure as a multipurpose platform to be connected.

“If you’re about to put in a whole new LED lighting system, what else can that light do? How can you transform and think about that infrastructure in a new fashion and format?”Allgood asks. “How can it interact with the citizens in a whole different way so that cities ensure that every single piece of infrastructure and investment that they’re making does more than just one thing?

“You used to carry around 10, 15, or 20 different things to do all the things that a phone does today. (…) We’re really trying to take that message and that concept and say, ‘Why can’t you do that with city services and infrastructure?’”

As these companies are proving, networks of smart technology aren’t limited to any specific industry or task. What they offer is the possibility of unprecedented efficiency—reducing your energy footprint, getting you places faster, and increasing your crop yield—largely by analyzing data that had previously gone uncaptured. So as experiments and success stories continue to emerge elsewhere—from connected pill bottles that make sure patients take their medication to clothes that track your biometrics—it ought to raise questions for the emerging breed of technologist-farmers to answer.

“How can robotics and automation make farming much more efficient,” asks Dror Berman, managing partner at Innovation Endeavor, the lead investor in CropX. “How can we use data sciences to make the farm more efficient?”

For now, these continue to remain open questions, but as a population bomb for a new generation approaches, today’s Malthusians should take consolation in Naam’s perspective. “The problems we face are incredibly serious, but not insurmountable,” he says. “In fact, that’s been the state of our global food situation for most of the last 200 years.”∎

“The Space Beyond”

acrylic on canvas

2015