Donald Trump’s Obsession With Time Magazine Makes Almost Too Much Sense

The now-fading publication evokes a distinct 20th-century kind of wealth and influence—like the Plaza Hotel and Elaine’s on the Upper East Side.

If you had to pick the year Time magazine’s “person of the year” jumped the shark, you’d probably start with 2006. That was when Time looked at the rise of open-publishing platforms like Wikipedia, YouTube, and Facebook, and decided the most influential person was the collective “you.” It was cheesy, trite, and had the exact effect Time wanted: Everybody talked about it.

Time’s annual “person of the year” designation has always been a gimmick, going all the way back to Charles Lindbergh in 1927. Time was once a scrappy upstart, but for decades it was a very serious must-read magazine. Now that the heyday of newsmagazines has receded, the spectrum of people who have ever held a physical copy of Time in their hands has shriveled. Yet the “person of the year” still creates a residual media buzz—attention that, as my colleague David Graham wrote in 2012, really isn’t justified. “Year-end wrap-ups,” he wrote, “simply aren’t news.”

Well, they’re not news until the president of the United States gets involved, anyway.

Donald Trump has always had a gift of making a big deal out of nothing. “I can only say that the press couldn’t get enough,” he wrote in The Art of the Deal in 1987. Back then, he was still trying to figure it out. Now, as president, whipping the press into a frenzy is, for Donald Trump, muscle memory.

“Time Magazine called to say that I was PROBABLY going to be named ‘Man (Person) of the Year,’ like last year,” Trump tweeted on Friday, “but I would have to agree to an interview and a major photo shoot. I said probably is no good and took a pass. Thanks anyway!”

The magazine wasted little time firing back: “The President is incorrect about how we choose Person of the Year. TIME does not comment on our choice until publication, which is December 6.”

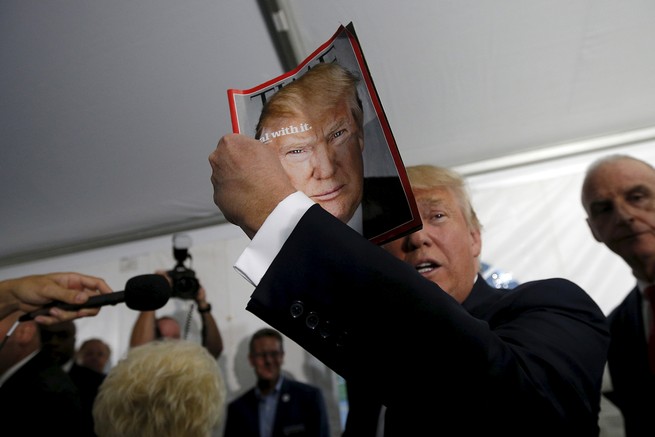

“Man of the Year”—it became “person” in 1999—is arguably the Trumpiest possible tradition in magazine journalism. And not just because of Trump’s apparent obsession with appearing on the cover. In June, The Washington Post discovered that what looked like a back issue of Time magazine featuring Trump on the cover—and displayed in at least five of Trump’s clubs—was, in fact, doctored. The fake cover featured a serious looking Trump with twin, glowing assessments: “Donald Trump: The ‘Apprentice’ is a television smash!” and “TRUMP IS HITTING ON ALL FRONTS . . . EVEN TV!” The real issue of Time magazine at the time featured the actress Kate Winslet on the cover.

One can only imagine the conversations that took place among the Time editorial team in the past 24 hours, but one thing almost certainly came up: Trump’s bizarre decision to insert himself into, of all things at this dramatic moment in American life, Time’s pick for a fading print-era tradition is decidedly good for business. (And, by the way, Time actually did name Trump “person of the year” in 2016.) This, at a time when the print-magazine business is generally not thriving. Time’s newsroom is still home to many great journalists, but the economic environment for newsweeklies is absolutely brutal. Remember Newsweek? It once routinely determined the national conversation. Not so anymore. (To answer your question, yes, Newsweek does still exist.) Meanwhile, the Koch brothers are backing the Meredith Corporation’s possible purchase of the storied publication, according to The New York Times.

One way to force people to—if not actually care—pay attention: a defiant tweet from President Trump. On one hand, why on Earth would Donald Trump—the president of the United States, Donald Trump—care what Time magazine is doing? On the other, of course Donald Trump is fixated on Time magazine’s “person of the year” contest. It’s as simultaneously weird and unsurprising as if Trump started griping about room service at the Plaza, or bar service at Elaine’s, or pick-your-own-1990s-New-York-City-reference. Donald Trump is a man whose concept of wealth is all Manhattan circa 1989. And in Manhattan in 1989, Time magazine was the king of the newsstand.

Trump became a public figure and a celebrity at Time’s apex. But more than that, Time is the perfect manifestation of Trump’s attitude toward success. To understand why a person like Donald Trump would gravitate toward a magazine like Time, you have to look at both of their histories.

In the 1980s, when Time was still a cash cow and Trump was still cementing himself as a mainstay on Page Six, Time was a very serious publication and Trump was a semiserious fixture in the tabloids. Cable news—Trump’s preferred journalistic medium today—was still in its infancy. Trump seemed preordained for gossip-rag stardom: There was the personal drama—an ugly divorce, a dramatic altercation in Aspen, the alleged infidelity with a beautiful eventual second wife—and, of course, the very public bankruptcy and surprising redemption. Trump enjoyed relentless pop-cultural relevance through it all—he had a cameo in Home Alone 2, remember—and seemed forever destined for B-list celebrity at best. Looking back at the media landscape of Trump’s younger years, the idea of Trump on the cover of Time seemed as silly as Trump buying the Plaza Hotel, or being elected president of the United States.

Donald Trump, we now know, is a man who is energized by the improbable.

Trump’s wealth—and the persona he built around it—has always been aspirational. The sprawling expanses of cold marble, the New Jersey gold fixtures, the aggressively nouveau riche aesthetic. The superlatives that spill so easily from Trump’s lips—everything’s the biggest, and the best, and the most. Time wasn’t so different at first. The magazine was founded by rich men playing with their fathers’ money—no member of the founding staff was more than three years out of college, the magazine’s historian Theodore Peterson once wrote. As my colleague Robinson Meyer and I wrote of Time in 2015, Time became the most powerful media instrument of mid-century America. In the early 1980s, as Trump was rising to fame, Time was absolutely flush with cash:

“So flush,” John Podhoretz wrote in Commentary, describing what it was like to work for Time in the 1980s, “that the first week I was there, the World section had a farewell lunch for a writer who was being sent to Paris to serve as bureau chief ... at Lutèce, the most expensive restaurant in Manhattan, for 50 people. So flush that if you stayed past 8, you could take a limousine home ... and take it anywhere, including to the Hamptons if you had weekend plans there. So flush that if a writer who lived, say, in suburban Connecticut, stayed late writing his article that week, he could stay in town at a hotel of his choice.”

All of it sounds absurd today, as over-the-top as the very idea of “person of the year.”

In 2006, when Time’s person of the year was “you,” Trump was riding out a triumphant phase in what had become a roller coaster of successes and setbacks—still basking in his fame as the host of The Apprentice, a reality game show on NBC.

Trump was 60 years old then, yet the experience was still formative in a way. The Apprentice was a hit, and it was measured in television ratings. Even when Trump became president of the United States of America—a spectacle so much bigger than any game show—he fixated on the size of the inauguration crowd. Old habits.

The man who wrote the Time story in 2006, the celebration of “you,” described his methodology at the time: “When you’re picking Time’s Person of the Year, you play a little bit historian of the future. What is the story of 2006 that people will remember? And more, I think, than any of the political or military stories, the shift in power from consumers of media becoming producers of the media ... that will really change a lot of things.”

Trump’s tweets are proof of this shift, evidence that Time’s “person of the year” pick in 2006 was actually prescient. Trump’s very presidency is not easily disentangled from this. Time matters to Trump, not just because of the narcissism it takes to care in the first place—let alone tweet about it—but because Time and Trump both arose in a bygone era. A moment of wealth and possibility in New York, and by extension America. Time always saw itself as the magazine for a very specific kind of American greatness. Trump, he swears, is just the same.