9 Questions With the Man Who Oversaw Higher Education Under Obama

Ted Mitchell has some advice for Betsy DeVos, Donald Trump’s pick to lead the U.S. Education Department.

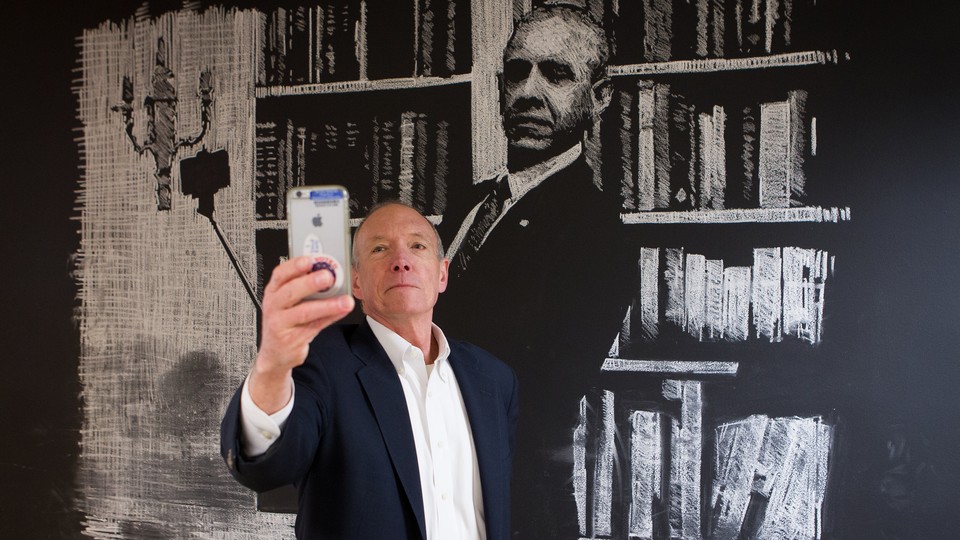

During his last day as the person in charge of higher education under the Obama administration, Under Secretary Ted Mitchell took a few minutes to talk to The Atlantic by phone about the U.S. Education Department’s accomplishments, failures, and what he plans to do once he hands in his government I.D. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

Emily DeRuy: As the president of Occidental College, you had to navigate federal government. Now that you’ve experienced it from the other side—as a government official working with college presidents—is there anything you wish you’d done differently as a college president?

Ted Mitchell: I wish that I had been more active in engaging with federal policymakers because, being on the other side, I know how much we look to college leadership and to the field in general for ideas, suggestions, and feedback. And I certainly wish that I had been more active in reaching out to [Margaret Spellings, George W. Bush’s education secretary from 2005 to 2009] and her team.

DeRuy: I want to touch on one point that’s been tough—President Obama’s goal of leading the world in college graduates by 2020. As of 2015, fewer than half of 25- to 34-year-olds have a degree, and the U.S. is behind South Korea, Canada, Ireland, Japan, and Luxembourg. Why has it been so hard to move the needle on that?

Mitchell: The president’s North Star goal of leading the world again has been an important imperative for us, and, as we’ve learned more, one of the things that is really quite important is the low completion rate in the U.S. Only around half of students who start a college education or a degree or certificate program finish that, and we need to make progress against that completion crisis. There are significant completion gaps between racial groups, between socioeconomic groups, and a powerful completion gap between traditional college students and nontraditional college students—or what we used to call nontraditional college students.

So in our policy view, we think that the focus needs to shift away from the image of the 18-year-old that gets dropped off at a leafy campus and picked up four years later, and we really need to think about the new normal college student—who’s just as likely to be a 24-year-old returning veteran, a 32-year-old single mom, a 50-year-old displaced worker. And the traditional structures and mechanisms for college don’t necessarily work for those students who need to consume their education in smaller chunks, who may need to go to school part-time while they're raising a family or holding down a job. We think of the president’s goal as presenting the nation with both a math problem—how to get the numbers up—and a moral problem—which is how to make college accessible and affordable for an increasingly diverse set of Americans.

DeRuy: I cover that a lot through our “Next America” project, focusing especially on students of color. But you referenced, for instance, a displaced worker and I’m wondering if you could talk about some of those other students—rural, white men who are grappling with the fact that they can’t graduate from high school and move straight into solid jobs anymore, for instance, including many of President-elect Donald Trump’s supporters—and what role colleges should play in connecting with them.

Mitchell: The president was clear, when he announced the America’s College Promise program, that the U.S. economy—in fact, the global economy—is one in which a high-school education isn't enough, and we need to think as a country about universal publicly funded education extending through the first two years of community college, or the first two years at a historically black college or minority-serving institution. And the crux of that is, in fact, the changing nature of work, the changing nature of the economy. And so our community colleges have a really unique and important role to play. Most Americans live within 25 miles of a community college. And that creates a great opportunity for access. Community colleges themselves have their thumb on the pulse of the local economy, and can—and are—developing programs that are specific to the local market needs of their communities.

DeRuy: Somewhat related to that, you spoke at Northeastern University recently about our viability as a democracy being intertwined with education, of universities as bastions of liberty and freedom, and about the risk to our democracy of retreating from that. And then in response to an audience-member question, you said we haven’t done our best work yet on righting and writing, both spellings, the narrative around education as an individual versus a public good. Expand on that a little.

Mitchell: Really since the Land-Grant College Act of 1862, American higher education, particularly public higher education, has been a compact between states, the federal government, and families and students. And what’s important about that is that there is an investment for each of those three, but also a return to each of those three. Clearly, individuals benefit. They improve their economic standing. They improve long-term health, the long-term stability of their families and communities. But the state and federal government also benefit. There is a public good here. And the public good can be expressed in the macro economy in terms of the growth in GDP, and the competitiveness of American businesses and industry. But it’s also the social and public good of a strong democracy, in which citizens are educated and formed and are able to be critical thinkers about the issues that are put in front of them, whether those are local community issues like the town budget, or big national and international issues like climate change or increasing inequality across the globe.

DeRuy: What is your biggest accomplishment, and what is your biggest failure?

Mitchell: I think that the biggest accomplishment of this administration has been to focus all parts of the higher-education community on student outcomes. And I think that’s been an important shift from looking at inputs and processes—to really ask the question, “How are students benefiting from this program, this institution, this investment in federal financial aid, this family investment?” And I think that our focus on outcomes is now rooted in institutions, it’s rooted in the accrediting process, and, increasingly, I think it’s rooted in the conversations that families have around the dinner table—I know around ours—about which colleges are providing the best outcomes for students. And in that, I think our College Scorecard has played a very meaningful role.

Biggest failure? The thing that I worry the most about is the completion crisis. I worry that we have not done enough working with institutions to increase the graduation rates, particularly for the most vulnerable students, for first-generation students, for low-income students, for minority students. There is good news: We’ve graduated the most diverse college graduating class ever. A million more African American and Latino students are in college today than there were when the administration began. But we still have to improve those completion rates.

DeRuy: I’d like to ask about for-profit education. It’s something the department has made a focus—reining in bad actors in that space. Is that something that you think will continue? When I talk to people who are concerned about the next administration, that’s something they worry about.

Mitchell: We care far less about the tax status of an institution than about its ability to serve students, and we’ve brought new information to the table to help students and institutions know their strengths and weaknesses. I mentioned the scorecard a moment ago. The gainful-employment rule is a powerful tool for individuals to use and for institutions to use to identify programs that are providing the kind of education that allows students to pay off their debt and move up the economic ladder.

And I think it’s important that it’s sent market signals to for-profit institutions and not-for-profit career colleges, as well. When we first did our calculations, there were about 37,000 career programs in the country. When we released our rates two weeks ago, it was down to about 29,000. We think that the industry is self correcting, that they’re taking these outcome measures seriously, and they’re consolidating all of the limiting programs that aren’t serving students well. I think that that’s a powerful positive trajectory for the industry. So I think through better information, and enforcement action where necessary, we’re working with the industry to provide better outcomes for students.

A big part of this administration’s theory of action has been that transparency and better access to information and data will drive decision making, whether that’s from students and families or institutions themselves. And we believe it’s critical for the next administration to continue to make information available to the public on a regular basis.

DeRuy: I don’t know whether you listened to the confirmation hearing for President-elect Donald Trump’s choice to lead the department, Betsy DeVos, but we still don’t know much about her positions on higher education, and she doesn’t necessarily have experience in that realm. What advice would you have for her or whoever becomes her under secretary on that point about completion?

Mitchell: I think the work continues. I think keeping a focus on outcomes will be critically important, and one of those outcomes critical to the nation and critical to individual students and families is completion.

DeRuy: What’s next for you?

Mitchell: I don’t know. I’m going to reintroduce myself to my family and go from there.

DeRuy: Anything that I haven’t asked that you’d like to say?

Mitchell: American higher education has been in the 20th century a real engine of opportunity for individuals and a real power in creating a diverse and engaged democracy. And it’s a treasure.