There’s a clip on YouTube of the Jesus and Mary Chain frontman Jim Reid at his hilarious and terrifying peak as an interviewee. It’s 1985 and he’s just been told, off-camera, by an assistant on a Belgian TV show that the host is a Joy Division fanatic, so on no account should he say anything bad about the band. Jim is a fan himself, but of course, he feels obliged to lay waste to Joy Division. The host looks like he wants to either throw a punch or throw up.

Twenty-nine years later, I meet Jim in Manchester, where he’s being interviewed for 6 Music by Mary Anne Hobbs. She gets a much easier time of it than the Belgian guy. Jim’s negativity, no longer weaponised, is dryly comical as he dismisses everything from his school days (“I wasn’t even important enough to be bullied”) to dancing (“I think I danced once in 1985”). The only subjects that elicit undiluted enthusiasm are the Velvet Underground (“the best band in the world ever”) and Francis Bacon, whose paintings he describes as “reality reconstructed in a way that it ought to have been in the first place”.

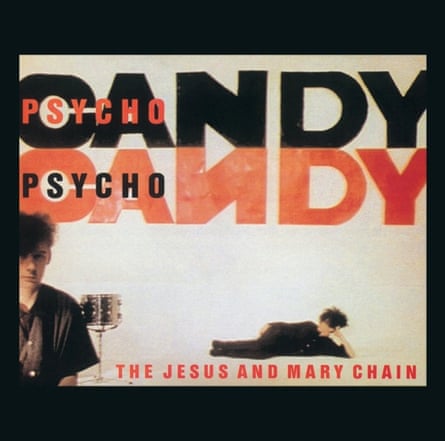

You could say the same of the 1985 album that Jim and his guitarist brother, William, are performing in full for the first time next month. Psychocandy (“it’s a one-word review of what it contains,” says Jim) was an explosive anomaly. Into the chasm between the expensive, imperial realm of pop and the insular, underachieving ghetto of indie erupted the most notorious band since the Sex Pistols, attended by riots, bans and breathless headlines, even though the Reids were painfully shy. Some of Psychocandy is beautifully wasted pop, like Lou Reed working in the Brill Building; some sounds like being trapped in a wind tunnel full of broken glass and bees; the rest sounds like both happening at once. The Jesus and Mary Chain were a band without a middle. There was only melody and noise, beauty and violence, love and hate.

“Contrast’s dead,” says Douglas Hart, who played bass in the Mary Chain before quitting in 1991 to become a successful music video director. “We live in this slightly anodyne world. That contrast was important psychologically. If you were pissing people off it made you feel great.”

Alan McGee, the Creation Records founder who made a fortune from Oasis, is managing the Mary Chain again almost 30 years after they fired him. He still sounds like their biggest fan, seeing them as a vital bridge in British rock between punk and the 90s. “I believed the Mary Chain were the greatest group in the world,” he gushes. “I genuinely believed they were the revolution.”

Speaking to the brothers separately about Psychocandy is both confusing and illuminating because they often disagree. Jim, who now lives in Devon and has two daughters, is very funny in a self-deprecating, Eeyoreish way. William, speaking from Los Angeles (he moved there in 1998) apologises for his inarticulacy and bad memory. “My 14-year-old son asks me these questions and I just say I don’t know,” he says pleadingly. “We just did it. I don’t know how we did it. It’s a little miracle. It could all have been different.”

The Reids grew up in the suburban new town of East Kilbride, “the edge of the universe”, spiritually distant from Glasgow, let alone London. You had to be a fantasist to think of making it from there. Unable to get their act together in time for punk (Hart calls the Mary Chain “a punk band out of time”), they quit their jobs in 1980. For the next three years they would stay up all night, fuelled by tea and biscuits, dreaming up the perfect band. “We were like weird twins in those days, finishing each other’s sentences,” says Jim. “We were very much of the same mind.”

Eventually, they imagined music that fused the noise of German industrial band Einstürzende Neubaten with the pop sweetness of the Shangri-Las. When they first heard The Velvet Underground & Nico, says Jim, “Our jaws hit the floor. They were the Mary Chain before the Mary Chain. That was the point at which we were kicked off our sofa.”

By 1983 Jim was 21 and William 24. William had given himself until his 27th birthday for the band to succeed before moving to Israel to work on a kibbutz. “I think everybody thought we were a couple of wasters, and, to be honest, we probably were,” says Jim. “We thought, well, if we don’t do this now, we’re never going to do it.”

That year their dad lost his factory job and gave his sons £300 from his redundancy pay-off. They spent it on a Portastudio to make demos of the songs that would become their first singles, Upside Down and Never Understand. Neither of them wanted to be the singer so they flipped a coin and Jim lost. “It could have gone the other way,” he says. “After a while I started to shag more girls than he did and he was like, ‘I want to be the singer!’ And I was like, ‘Sorry, son, the coin doesn’t lie.’”

“I’ve got a great job,” counters William. “I get to hide in the shadows and do what the hell I want. Jim’s got to be the guy that everybody looks at.”

Despite the unfavourable odds, the Reids felt confident because they felt necessary. “We hated the 1980s music scene,” says Jim. “I mean, we detested it. The Mary Chain were more influenced by bad music than good. We did well out of that. We only started a band because we thought, ‘Why isn’t anyone else doing this?’”

Through a stroke of luck their demo tape reached future Primal Scream frontman Bobby Gillespie. He sent it to his friend Alan McGee, who released Upside Down on Creation and became their manager. “McGee’s enthusiasm was a driving force,” says Jim. “He was like your battery charger. You’d look at Alan and he’d be frothing at the mouth and you’d be like, ‘Fucking hell, he’s right!’”

After recording Upside Down and hiring Bobby Gillespie as their drummer in late 1984, the Mary Chain looked for a major-label deal. “We had expectations we were going to be the Beatles or the Stones, so you have to go big,” says William. “We had huge balls.”

They soon signed to Blanco Y Negro, the WEA subsidiary established by Rough Trade’s Geoff Travis. Jim’s biggest regret is that they didn’t choose Rough Trade. “At the time, everyone was indie-schmindie,” explains Jim. “I wasn’t interested in a spotty kid with an Oxfam jumper playing in a room above a pub to his 22 mates. I wanted to be Marc Bolan, David Bowie, Jim Morrison. I saw us at Wembley Stadium. What I didn’t realise was that Warner Brothers weren’t interested in the Mary Chain. Nobody there liked the band, nobody there did anything for the band. There was a sense that people just wanted you out of the building as quickly as possible.”

At times it seemed the whole music industry was resistant to them, like a body rejecting a transplanted organ. They butted heads with pressing plant workers who refused to manufacture the pungently named B-side Jesus Fuck and BBC sound engineers who wanted to “fix” the band’s unorthodox sound.

“You’d go to the toilet and come back and the guitars were all turned down,” remembers Jim. “We didn’t know what the rules were. What we did know was what sounded good.”

Then there was their live reputation. They drank heavily to drown their nerves, so their early shows, sometimes as short as 15 minutes, projected chaos and alienation which a growing number of troublemakers mistook for violence. When they played the North London Polytechnic in March 1985, audience members trashed the stage while the band hid in their dressing room. The music press reported a “riot”; McGee, in the spirit of Malcolm McLaren, excitedly declared it “art as terrorism”; suddenly the band’s reputation was out of control.

“After that, you had to come to a Mary Chain gig with a baseball bat,” says Jim. “The notoriety did sort of… spiral, and we had to nip it in the bud.”

“That was McGee trying to make it an event,” says William. “We had a lot of arguments with him about that. It wasn’t Alan going on stage and being a target for these lunatics. It was us.”

The Reids’ scabrously self-aggrandising interview style, however, was all their own work. They used words the same way they deployed white noise and feedback: to provoke and excite but also to conceal their shyness. “To knock things down that people held in high regard got you noticed,” says Jim. “A lot of it was bravado. You’re almost trying to talk yourself into it. Nobody else is saying this so we will: we’re better than the Beatles.”

“A lot of people thought we were snotty little brats,” says William. “We were snotty little brats. You need a bit of that when you’re young, don’t you?”

To the hysterically impatient 80s music press, the Mary Chain felt electrifying but not necessarily built to last. Only the brothers knew that they had a fistful of great songs that had never been played live. William was the more prolific songwriter but Jim was a shrewd editor and together they were formidable.

“‘Mary Chain’ and ‘hype’ were synonymous,” says Jim. “We knew that a lot of people thought Psychocandy was going to be the singles and a collection of B-sides. So we were quietly confident, quite smug about it. We felt as if everything on Psychocandy was a potential single.”

The songs were one secret weapon; their discipline was another. The men who always performed drunk recorded Psychocandy entirely sober: “Lots of tea and Wimpy [burgers], not speed and alcohol,” says Hart. The apparent chaos was in fact meticulously choreographed: they sampled white noise and feedback and carefully punched it into the mix. Getting the sound exactly right is why the album, recorded at north London’s Southern Studios with engineer John Loder, took six weeks.

“To us, it seemed like an eternity,” says Jim. “We thought we were budding Phil Spectors. I’m sure a fly on the wall would have been thinking: ‘These guys are nuts.’”

Musical disagreements were sometimes settled with fists. At one point Jim threw William into a studio door with such ferocity that it came off its hinges. “They were really great at fighting [verbally] because they could push each other’s buttons,” Hart says admiringly. “Sometimes I would stand by in awe. How can people slag each other so beautifully? And then they’d start throwing punches and you’d have to intervene.”

The Reids felt “pretty cocky” about Psychocandy and critics adored it, but the industry remained frosty. According to Jim, Warner Music UK chairman Rob Dickins told them, “Nobody’s going to buy it.” Radio 1 DJ Mike Smith blacklisted follow-up single Some Candy Talking because he was convinced, wrongly, that it was about heroin. When the Mary Chain toured the US, their Jesus Fuck T-shirts didn’t go down well. “The promoter in Texas said, ‘They’ll lynch you,’ so he put a bit of tape [on the T-shirts]. He put the tape over the word ‘Jesus’ and left the word ‘Fuck’.” Jim rolls his eyes. “That speaks volumes.”

The Reids’ shyness made even cult success hard to enjoy. “They were fucking miserable,” says McGee. “We’d been offered Top of the Pops and they were looking at me like I’d asked if they wanted to take a walk around Auschwitz.” Jim rejects this (“McGee’s talking bollocks”), but Hart seems to concur. “When bands are great they create a little gang mentality that excludes others by necessity. Our spiky reputation would go before us, which we enjoyed at first, but after a while you get a bit lonely and think: ‘Why aren’t we having a good time?’”

At any rate, the brothers’ reticence created a glass ceiling. As songs such as In a Hole and My Little Underground made clear, the Mary Chain were introverts. Their wall of noise was defensive rather than aggressive, a prickly cocoon that anticipated the hermetic roar of My Bloody Valentine. However great the songs, they lacked the common touch, so how on Earth did they ever believe they’d play Wembley?

“What were we thinking?” Jim agrees. “Psychocandy in a stadium? It was never going to happen. But we had such utter self-belief. We were absurdly naive.”

In retrospect, it was for the best, because the Reids weren’t primed to withstand celebrity. “Massive fame would have probably screwed with my head,” agrees Jim. “I think William would have enjoyed the adulation.”

William flatly disagrees. “I really think we would have fallen to pieces.”

Instead, the Jesus and Mary Chain fell to pieces slowly. Starting with 1987’s cleaner-sounding Darklands (William’s favourite), each subsequent Mary Chain album was good and different but each one took longer to make as they drank more and spoke less.

“In 85 I drank to get over my nerves; in 97 I drank because I just had to,” says Jim. “That process gradually ended up with me being an addict. I’d be sitting in the living room with a bottle of whisky and phoning up my dealer to get a gram of coke. But [despite] the drugs, the drink, the bickering, the music never suffered. I stand by every record we made.”

After William quit the band in 1998, during an onstage punch-up in LA, the brothers didn’t speak for a year or perform together for almost a decade. Since their first reunion show at the Coachella festival in 2007, where Scarlett Johansson joined them for Psychocandy highlight Just Like Honey, they’ve maintained enough harmony to tour regularly and work on a seventh album that, Jim promises, “will be bloody good”.

I ask Jim to describe their relationship and he sighs heavily. “Oh God. It’s complicated. We tolerate each other. I know how to wind him up, he knows how to wind me up. Sober, we give each other space. Bring drink into the equation, it can get a bit bloody again.” On this subject, unusually, William is in complete agreement.

The impossibility of recreating the turmoil and combat of 1985 in front of a reverential older crowd led the Reids to decline previous offers to tour Psychocandy, but now it’s part of the appeal. “Even when the album was out, it was about riots and falling over drunk on stage,” says Jim. “It was about everything but the music. If you’re looking for skinny young kids in a strop, kicking their guitars, stay at home.”

I ask William how he thinks the audience would react if they regressed 30 years, got drunk, played for 15 minutes and stormed off. He sounds intrigued.

“What if we did play exactly what we did in 1985?” he muses. “I wonder if people would embrace it.”

The Jesus and Mary Chain’s five-date UK tour, Psychocandy Live, begins at London’s Troxy on 19 November. Jim Reid is on Mary Anne Hobbs’s 6 Music show on 1 and 2 Nov

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion