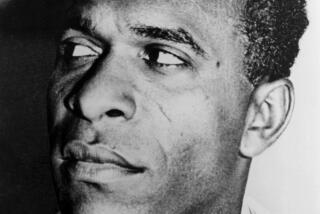

William H. Grier dies at 89; psychiatrist and co-author of ‘Black Rage’

When psychiatrists William H. Grier and Price M. Cobbs were writing their groundbreaking 1968 book on race, its working title was “Reflections on the Negro Psyche.”

However, in a stroke of inspired editing, they changed it to more precisely reflect their controversial subject.

“Black Rage” became a classic in its field.

Grier, 89, died Sept. 3 at a hospice in Carlsbad, near his Encinitas home. He had a brain lesion, his son Geoffrey Grier said.

When they first collaborated, Grier and Cobbs were in a minuscule cohort of African American psychiatrists. Deadly riots were flaring in cities across the U.S. — and, in an analysis blending patient case studies and an uncompromising focus on history, the authors predicted even worse.

“There can be no more psychological tricks blacks can play upon themselves to make it possible to exist in dreadful circumstances,” they wrote. “No more lies they can tell themselves. No more dreams to fix on. No more opiates to dull the pain. No more patience. No more thought. No more reason. Only a welling tide…now a tidal wave of fury and rage, and all black, black as night.”

“Black Rage” became required reading in college classes on the psychodynamics of race relations.

Years later, Grier summed up the book’s thesis for the Toronto Star.

“There is an inclination on the part of white people to deny the history of race in this country, to say that race relations began when they were born, that they haven’t lynched anybody, that they haven’t enslaved anybody, so all that stuff’s irrelevant,” he said.

But “if you don’t go back to slavery,” he said, “you’d have to assume that all living blacks are geniuses at digging a hole for themselves.”

Born Feb. 7, 1926, in Birmingham, Ala., Grier was the only child of a postal worker who lost his job unfairly when Bill was 12. The family moved to Detroit and lived for at time with relatives – an upheaval that Grier said was due to racial prejudice.

At 19, he graduated from Howard University in Washington, D.C. He later received his MD from the University of Michigan and did his residency at the Menninger School of Psychiatry in Topeka, Kansas.

Sent overseas during the Korean War, Grier contracted polio. The disease left him with a permanent limp and reliance on a cane or crutches, but doctors had told him he wouldn’t walk again.

Grier practiced psychiatry in Detroit before moving to San Francisco, where he met Cobbs.

In his 2006 memoir, Cobbs said his longtime friend “understood clearly the psychological burden of a people who had been pushed to the outside, forced to stay there, and given very little room for moving from that exiled state of being.”

“Although we were writing about the clinical state of the Negro psyche, Bill and I were really describing exposed nerves, violently suppressed anger, teeth-grinding frustration, and outrage on the part of black people from every level of society,” Cobbs wrote.

Most critics praised “Black Rage,” but in the New York Times, African American psychiatrist Kenneth Clarke said the authors had followed the fashion of the day into a “sadomasochistic orgy of black rage and white guilt.” He objected to their work’s lack of documentation.

The co-authors replied that their motive was to “involve the reader. We deliberately did not footnote our book, knowing that no social revolution is brought about by footnotes.”

The two teamed up again in 1971, co-writing a book on black churches called “The Jesus Bag.” It was not a success.

But “Black Rage” continued to sell. In addition to influencing the national conversation on race, it helped validate psychotherapy in the black community, Geoffrey Grier said.

“It wasn’t something that a lot of people of color ascribed to,” he said. “Only after ‘Black Rage’ did it become OK to talk about therapy or psychiatry or mental health. Prior to that, it was cocktail conversation, an alternative for the affluent.”

As Grier aged, he remained intensely interested in race relations but grew disenchanted with the practice of medicine. “He saw insurance companies reigning over treatment decisions,” Grier’s son said. “He thought it was criminal.”

In addition to Geoffrey, Grier’s survivors include his wife, Connie Ort; son David Alan Grier, the comedian and actor; daughter Elizabeth; stepson Derrek Karmoen; stepdaughter Saminah Karmoen; and two grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.