Bezos Prime

Bezos Prime

Amazon’s CEO has driven his company to all-consuming growth (and even, believe it or not, profits). Today, though, as he deepens his involvement in his media and space ventures, Bezos is becoming a power beyond Amazon. It has forced him to become an even better leader.

I.

When Washington Post correspondent Jason Rezaian was freed from an Iranian prison in January after having been held for 18 months on vague charges of espionage, he traveled on a Swiss military aircraft to a U.S. base in Germany. A short time later the Post’s proprietor, Jeff Bezos (No.1, World’s Greatest Leaders), showed up to bring Rezaian home. “It’s an inescapable part of the mission of the Post to send some people into hostile environments,” reflects Bezos of Rezaian, who was detained while reporting in Iran. “And what happened to Jason and his wife, Yegi, is completely unfair, unjust—outrageous. I considered it a privilege to be able to go pick him up. I had dinner with them at the Army base the night that I got there, and then he was getting released after his debriefing the next day, and I asked him, ‘Where do you want to go? I’ll take you wherever you want.’ And he said, ‘How about Key West?’ I was like, ‘Okay!’ And that’s what I did. I dropped him off in Key West. He and Yegi had only been married for just over a year before he got imprisoned. It was almost like a second honeymoon.”

Reporter Jason Rezaian (left) and Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos aboard a private aircraft before it took off for the U.S. on Jan. 22.Photograph by Douglas Jehl—The Washington Post

A jubilant photo of reporter and owner inside the latter’s jet quickly made the rounds. Asked if he meant to make a statement by personally retrieving his employee, Bezos replies, “I did it just for Jason. My motivation is super simple. But I would be delighted if people take from it the idea that we’ll never abandon anybody.”

It’s an unexpectedly sunny mid-March morning in Seattle, and Bezos’s disposition is even sunnier. Who can blame him? Amazon’s (AMZN) market value is $260 billion, with Bezos’s stake worth $46 billion. Bigness hasn’t sapped its growth: Sales jumped 20%, to $107 billion, last year, and Amazon surprised investors with operating profits of $2.2 billion, a 12-fold increase from 2014. The Post, a declining icon before Bezos bought it for $250 million in 2013, is bubbling with new ideas. Even Blue Origin, the secretive rocket-ship company Bezos funds out of his own pocket, is enjoying a moment of prominence, having promised to blast off with space tourists in a few years.

To say all this leaves Bezos energized would be an understatement. Dressed in jeans and a checkered shirt, sleeves rolled up to the elbows, the notoriously intense CEO is the picture of contentment. He’s deploying his trademark cackle—the auditory equivalent of Steve Jobs’ signature black turtleneck—liberally. Says Bezos: “I dance into the office every morning.”

He’s got every reason to cha-cha. More has gone right for Bezos lately than perhaps at any other time during his two-decade run in the public eye. His company is expanding internationally and spreading its hydra-headed product and service offerings in unexpected new directions. Bezos, too, is evolving. Always a fierce competitor and stern taskmaster, he has begun to show another side. With the Post, he’s taken a seat at the civic-leadership table. And with his various projects Bezos is also becoming known as a visionary on topics beyond dreaming up new ways to gut the profit margins of Amazon’s many foes.

Bezos is preternaturally consistent. He still preaches customer focus and long-term thinking. Yet of necessity, as Amazon has become massive—and as he has indulged his eclectic and time-consuming pursuits—he has become the sort of leader who empowers others. “He was at the center of everything at the beginning. The leadership was Jeff Bezos,” says Patty Stonesifer, the former Microsoft (MSFT) executive and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation CEO who has been on Amazon’s board for 19 years. “Today it’s not a hub-and-spoke connecting to him. He has become a great leader of leaders.” Indeed, his evolution portends dramatic repercussions far and wide: The possibilities of a less tethered Jeff Bezos are equal parts exciting (imagine what he’ll do) and terrifying (pity whom he’ll crush).

—Patty Stonesifer, Amazon director for 19 years

II.

Editor Marty Baron is discussing how the Washington Post has changed since Bezos became his boss. It’s a blustery February afternoon in Washington, D.C., days before Baron will fly to Los Angeles to attend the Academy Awards. Spotlight, the film about a team of truth-and-justice-seeking journalists at the Boston Globe, where he was then the editor, will win the Oscar for best picture. Baron, by the way, is exactly as Liev Schreiber portrayed him in Spotlight: a dour and serious—yet witty—newsman.

Baron sits at a small table in his not particularly grand office in the Post’s new downtown Washington headquarters, which is more lobbyist chic than hot-type-in-the-basement gritty. He explains that Bezos’s chief editorial contribution has been to “push us into the recognition that living in the world of the Internet is different from living in a print world.”

Annoyed that “aggregator” sites were getting more online traffic by summarizing Post articles than the Post received for the original articles, for example, the Post has become an adept aggregator itself, “layering on top,” in Baron’s words, its own reporting. Bezos approved funding for a Huffington Post–like site, PostEverything, for experts to publish their opinions. (Some write for free; the Post pays others.) Then there’s the Post’s new “talent network,” a highly automated web creation that connects the publication to 800 freelance journalists in the U.S. who can be assigned articles in seconds. Baron compares the network to tech-world innovations like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, TaskRabbit, and Uber. “We’re not in a position where we can reconstruct an old model of bureaus all over the country,” he says, “and it’s not clear that that’s the most efficient and effective way to go about our work.”

It’s unnerving to hear the current “it” editor of American journalism waxing eloquent about outdoing the Huffington Post, pooh-poohing the need for far-flung staff correspondents, and describing how the Post employs the work of other sites. Is he really okay with all this newfangled, journalistically questionable fare? Says Baron: “I have no interest in dying gracefully.”

For his part, Bezos professes his belief in the Post’s democracy-sustaining mission—if not its potential to increase his wealth. “I would not have bought the Washington Post if it had been a financially upside-down salty-snack-food company,” he says. Bezos describes being 10 years old, sprawled on the floor of his grandfather’s house, watching the Watergate hearings. The Post, of course, achieved its maximum renown covering that political scandal. “We need institutions that have the resources and the training and the skill, expertise, to find things,” Bezos says. “It’s pretty important who we elect as President, all those things, and we need to examine those people, try to understand them better.” (Bezos emphasizes he’s not looking to buy any other publications, though he is regularly solicited.)

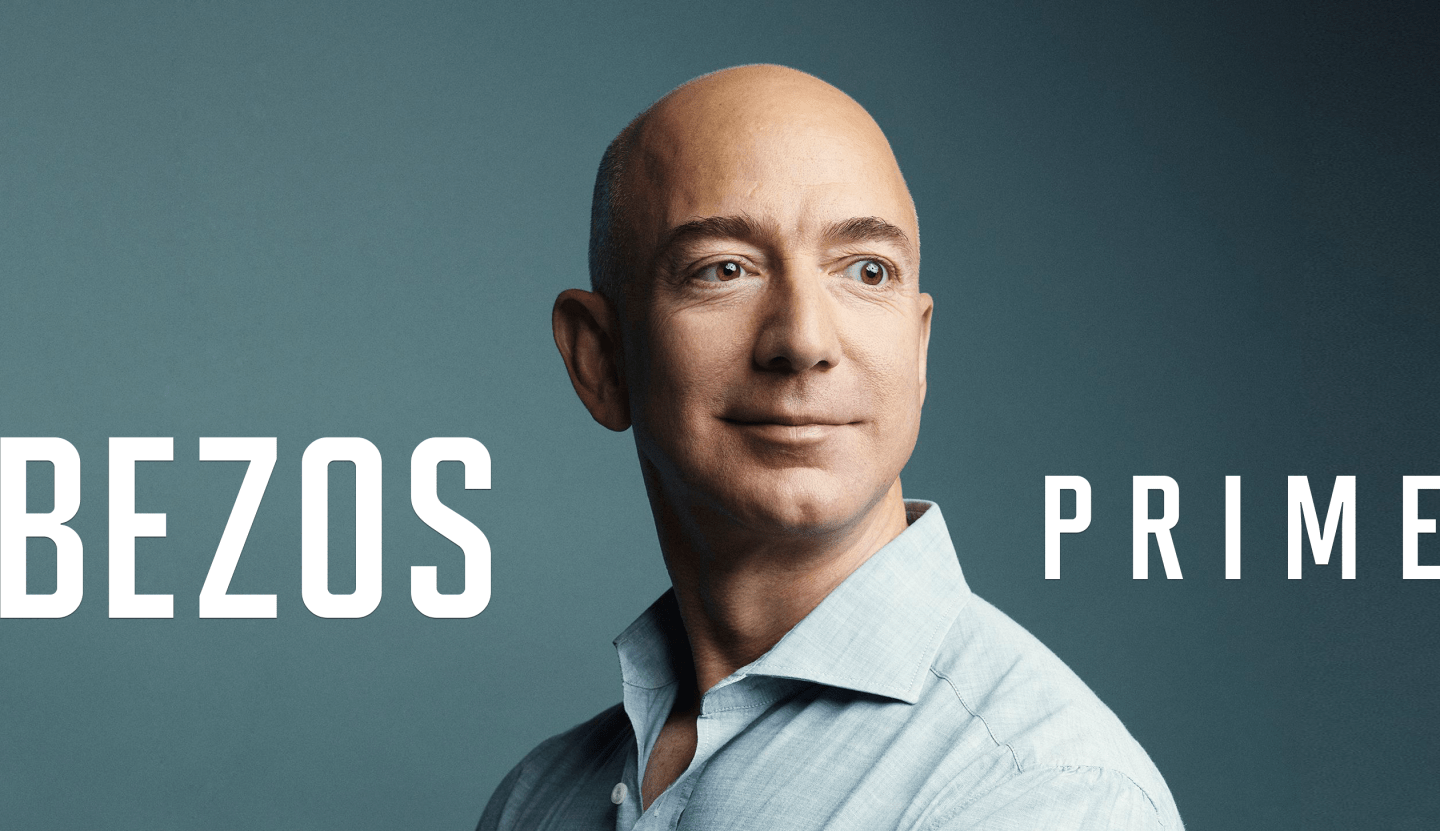

Jeff Bezos, photographed at Amazon headquarters in Seattle on March 11, 2016.Photograph by Wesley Mann

Former Post owner Don Graham, whom he had known for 15 years, approached him through an intermediary and said Bezos could give the publication financial security and the benefit of his Internet experience. “This is the first company I’ve ever been involved with on a large scale that I didn’t build from scratch,” says Bezos. “I did no due diligence, and I did not negotiate with Don. I just accepted the number he proposed.” (Graham, who has been publicly mum on the Post since selling it, declined to be interviewed.)

By two measures—web traffic growth and volume of new ideas—the Post is thriving under Bezos. (Bezos, not Amazon, owns the operation. The Post releases no financial data, but it’s a safe bet that it’s losing money, given the many investments it’s making.) Monthly web visitors have skyrocketed from 30.5 million in October 2013 to 73.4 million in February this year, the result of vigorous product development.

Bezos has no operational role at the Post, but he does keep close tabs. He meets by phone every other week with the news organization’s top managers, including Baron and Post publisher Fred Ryan, former president of Allbritton Communications, whom Bezos recruited to replace Graham’s niece, Katharine Weymouth. Twice a year the team goes to Seattle for an afternoon of meetings with Bezos, followed by dinner.

When he bought the Post, there was speculation that Bezos wanted to control the editorial product. Bezos says he has no such interest, and Baron confirms Bezos doesn’t suggest coverage. However, the owner does throw his weight around on wonky issues like web-page load time and ease of subscription sign-ups, both examples of what Bezos likes to call matters of “customer obsession” that resonate with his Amazon experience. Shailesh Prakash, the Post’s chief product and technology officer, says that in his sphere Bezos is downright “pushy,” which he means as a compliment. For example, Bezos encouraged Prakash’s team to develop Arc, a collection of publishing tools, even though off-the-shelf products were available. Amazon, he told Prakash, could have used IBM (IBM) software when it started out. Instead it built its own, a business that led to Amazon Web Services (AWS), a runaway financial success. “He’s involved. Very involved,” says Prakash, a former digital executive at Sears (SHLD) who joined the Post before Bezos’s purchase. “My engineers and I enjoy that a lot. I suspect Jeff enjoys that too.”

Sometimes Bezos’s creativity gets the better of him. Prakash says the owner suggested a gamelike feature that would allow a reader who didn’t enjoy an article to pay to remove its vowels. He called it “disemvoweling,” and the concept was to allow another reader to pay to restore the missing letters. The idea didn’t go far, Prakash says, noting that “Marty wasn’t very keen.” Bezos, an unrepentant believer in the power of brainstorming, says, “Working together with other smart people in front of a whiteboard, we can come up with a lot of very bad ideas.”

Post people seem to value most that Bezos provides them air cover while they fiddle with ways to survive the transition from print to digital. Hiring has ramped up significantly under Bezos, providing more resources for serious journalism too. Ryan, the publisher, credits Bezos with demanding risk taking—without fear that failure will be punished. “That provides a sense of invigoration, particularly when other publications are in this mode of ‘If this doesn’t work, there’ll be hell to pay next quarter.’ ” So long as Bezos is enjoying himself, in other words, there is no next-quarter deadline for the Post anymore, just more opportunities to reinvent journalism, preferably in a way that eventually makes money.

III.

When you walk through the unmarked doors of the offices of Blue Origin in an industrial area near the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, you quickly realize you have entered space-nerd heaven. A 30-foot-tall globe of the earth spins inside the entryway. Up a flight of stairs to the lobby is a combination first-rate space museum and model hobbyist’s paradise. A canopy over a central fireplace is the base of a Jules Verne–inspired rocket ship, the flames beneath it throwing off real heat. Nearby, a replica of the U.S.S. Enterprise, of original Star Trek fame, stands guard over paraphernalia recovered from actual space missions, including a fuel-flow control valve from an Apollo lunar control descent engine.

All these artifacts come from the personal collection of Bezos, a science-fiction buff since childhood. Indeed, everything in the vast building belongs to him. That includes the reusable spacecraft, the New Shepard, that Blue Origin is developing, and its soon-to-be-tested rocket engine, the BE-4. Bezos himself intends to be onboard in several years, when Blue Origin is ready to fly humans.

Blue Origin’s New Shepard rocket, which flew to space and returned to the same launchpad.Photograph courtesy of Blue Origin

Bezos quietly started Blue Origin 16 years ago as a research project and has been mostly mum about it until now. Rob Meyerson, a soft-spoken Midwesterner and former NASA aerospace engineer who is its president, says the stealthy profile largely has been an effort to avoid hyping unproven technology. Meyerson, who worked at a private Seattle-area rocket company called Kistler Aerospace, which went belly up, joined Blue Origin in 2003 when it had about 10 employees. At the time, Bezos had charged his researchers with finding an alternative to the polluting and earsplitting blastoff methods that space programs have used since the 1960s. The research failed, and Bezos changed his mind. “Jeff realized we should invest in liquid propulsion so we could fly a lot,” says Meyerson. “All of this is tied to his original vision of having millions of people living in space.”

After years of fits and starts, Blue Origin is finally ready to go airborne. It has successfully sent an automated spacecraft into suborbital space—about 100 kilometers above earth, known as the Kármán line, a 10-minute trip from start to finish—and landed it safely on earth. The company won’t say when, but it plans shortly to begin taking reservations for passengers. It intends to develop a rocket to fly into earth’s orbit, a feat Elon Musk’s SpaceX has already achieved, which will allow it to carry humans and satellites. “Eventually,” says Meyerson, “we want to sell these things to customers. We think we’ll start flying passengers in 2017. These will be test engineers. Then we’ll sell tickets. I imagine Jeff and I will fly in the 2018-ish time frame.”

As with the Washington Post, Bezos is regularly engaged with Blue Origin, though in a nonoperational role. Meyerson says Bezos attends a daylong monthly operational review that often includes presentations by outside experts. He also visits for weekly four-hour updates on the progress of its orbital launch vehicle and New Shepard spacecraft. Meyerson says he initially resisted writing the famous six-page “narratives” Bezos requests before meetings, where PowerPoint is banned. Bezos kept asking, though, and Meyerson relented. Now, he says, he’s a “complete convert.”

Bezos won’t say how much money he has sunk into Blue Origin. Reports several years ago put the figure at $500 million, and the company’s spending velocity has only increased. It has 600 employees on the way to 800, with launch facilities in Texas and soon at Cape Canaveral, Fla. “Nobody gets into the space business because they’ve done an exhaustive analysis of all the industries they might invest in and they find that the one with the least risk and the highest returns on capital is the space business,” says Bezos. With his fortune, he can fund rockets for quite a while to come. Indeed, were Bezos to keep blowing through $500 million a year on Blue Origin, he would have to close the place … in 90 years.

—Bezos, on the rocket business

IV.

In Seattle, I visit the new Amazon Books prototype store in a mall near the University of Washington. Located next to a Banana Republic and across from a Tommy Bahama shop, the store’s very existence is ironic for a company considered responsible for the near extinction of chain bookstores. Once there was a Barnes & Noble (BKS) in this mall, before it got Amazon-ed.

As far as concept stores go, Amazon Books is clever. All but the middle is devoted to books, stacked 10 or so deep; all face out. (Other booksellers charge publishers for face-out placement; Amazon does it on the assumption that customers prefer it.) Placards beneath the books contain customer reviews from Amazon.com, curated by employees. The center of the store is a showroom for Amazon’s burgeoning device business—including Echo personal assistants and Kindles of various sizes—as well as a flat-screen monitor highlighting Amazon’s TV and film offerings. The store’s capabilities are limited. It doesn’t offer store pickup or returns for Amazon.com purchases, for example. Other ideas demonstrate the promise of offline/online retail. For instance, if you use a credit card associated with your Amazon account, you’ll promptly receive a receipt by email. All in-store prices match those on Amazon’s website.

Inside Amazon’s first bookstore, in a Seattle mall that used to house a Barnes & Noble.Photograph by George Rose—Getty Images

At Amazon’s headquarters an hour later I tell Bezos where I’ve been and that I bought a book, Coraline, by Neil Gaiman, for my daughter. He thanks me for my business, emitting one of his uproarious laughs, and I tell him I don’t think it’s going to help much: The paperback cost $3.94 plus tax. He bursts out laughing again.

Every little bit counts, of course, and Amazon is adding bits across its vast empire at a furious pace. Its Amazon Web Services business, with $7.8 billion in sales in 2015, has grown so ubiquitous that it now effectively exacts a tax, as venture capitalist Chamath Palihapitiya has called it, on every startup to run its business. Every day seems to bring another experiment. Amazon’s efforts to compete against Apple’s (AAPL) iPhone failed miserably. But Amazon’s Echo personal assistant devices running on its Alexa natural-language engine have won rave reviews for superior performance compared with Apple’s Siri. Amazon is cranking up an ambitious same-day delivery program, becoming a major force in TV and movies, and has made moves to operate its own air and shipping transportation fleets.

It’s all too much for Bezos to micromanage, and he acknowledges picking his spots. His latest passion is for higher-end fashion, an area Amazon has been upgrading in recent years; Bezos says he is focused on Amazon’s plans for its own private label. “I think there’s so much opportunity for invention there,” he says. “It’s very hard to do online. It’s fragmented offline. People value a curatorial approach.” This, he says, is a significant departure for Amazon. “We didn’t curate a selection of books.” As for Bezos’s other areas of focus at Amazon, he says he’s spending time on “certain elements of AWS, but out a few years,” as well as on Alexa and the company’s fulfillment centers. As for specifics, “I can’t really share any because it’s too much of a road-map kind of issue.”

One reason Bezos can concentrate narrowly at Amazon is the length of tenure of his top lieutenants. Jeff Wilke, for example, joined Amazon in 1999, and today he runs Amazon’s consumer business, which he calls “Amazon Classic.” He says Amazon’s annual planning process—and the detailed narratives its managers prepare for them—allows Bezos to closely “audit” the company’s efforts. Otherwise, says Wilke, “I would say his style has gone from being more prescriptive to teaching and refining.” Jeff Blackburn, an 18-year Amazon veteran who runs the company’s M&A activities and content businesses, describes Bezos as consistent in his selection process. “He still works 65 hours a week. He’s still connected to the office and doesn’t travel very much. He dives in on the same issues now that he did many years ago.”

—Jeff Wilke, Amazon SVP, consumer business

One thing that has changed at Amazon is the level of scrutiny it endures. Brad Stone’s 2013 book, The Everything Store, lauded Amazon’s successes while portraying its treatment of partners and suppliers as shabby. A 2015 exposé by the New York Times portrayed life at Amazon as only marginally more pleasant than in a Soviet gulag. The severe depiction cascaded through the media, and Bezos told employees that “the article doesn’t describe the Amazon I know.” Asked how the criticism has affected him and Amazon, Bezos deflects the question with a politician’s ease. “A company of Amazon’s size needs to be scrutinized,” he says. “It’s healthy. And it’s a great honor really to have a company that has grown into something worthy of such scrutiny.”

Amazon had long been known as a grueling place to work, but the Times article struck a nerve. Amazon fired back by criticizing the paper’s journalism in a post on Medium by its senior vice president for communications, Jay Carney, a former spokesman for President Obama (and former writer for Time, Fortune’s sister publication). The controversy cooled, and Amazon says it hasn’t affected hiring. To this day, Bezos insists Amazon’s intense culture is a strength, not a weakness. A company spokesperson notes that Amazon has implemented a few HR modifications—such as an improved parental-leave program—but then hastens to add that the changes were in the works before the Times article. In the end, the consensus is that Amazon’s culture is every bit as ferocious and demanding as it ever was. Did you really expect Bezos to abandon the formula that got him here?

—Bezos, on how his company’s culture was represented

V.

Bezos is now 52. (“A full deck of cards,” he blurts out, laughing loudly at his own joke. “Next year I’ll have a joker.”) He is both at the height of his powers and willing to entertain thoughts of becoming a senior statesman. Asked if he has sought out role models for this phase of his career, he broadens the question. “I have been blessed my whole life with great role models.” A few he names include his parents, as well as J.P. Morgan Chase’s (JPM) Jamie Dimon (“I ask Jamie questions. I think he has a really good outlook on life and is very inspiring”), and Warren Buffett. “If I ever have a different opinion than Warren Buffett, my regard for him is so high, I always assume I’m missing something.”

Bezos is also embracing the role of thought leader. In late March, Amazon hosted a most unusual conference in Palm Springs. For the event, dubbed MARS, for “machine learning, home automation, robotics, and space exploration,” Bezos and some top deputies curated a group of thought-leader attendees and “scientists, professors, entrepreneurs, hobbyists, and imagineers” in these fields to give talks and conduct demonstrations. Each of the areas have direct relevance to Amazon or Blue Origin, but the company stressed to attendees that the conference was strictly noncommercial. Amazon wasn’t trying directly to sell anyone anything. Says Bezos, ahead of the event: “I’ll be satisfied if every participant who comes walks away having made a couple of new friends, having had some fun, and maybe being inspired by something amazing.”

The billionaire’s literary interests have always been eclectic, often unpredictably so. When I interviewed him in 2012 he had just finished reading a science-fiction book, The Hydrogen Sonata, by Iain Banks. Now he’s reading Jonathan Franzen’s new novel, Purity, which he says, “three different people recommended to me.” He has also just completed the first four chapters of an untitled novel by his wife, MacKenzie, which he describes in great detail but only on the condition that I not write about it without his receiving her permission—which she subsequently withholds. “I’ve been happily married for 23 years, and I’d like to keep it that way,” he says. There are limits, after all, even to the powers of Jeff Bezos.

A version of this article appears in the April 1, 2016 issue of Fortune.

This article incorrectly stated that contributors aren’t paid to write for the Washington Post’s PostEverything section. Some writers are paid.