Star biologist pinpoints role of microbes in disease

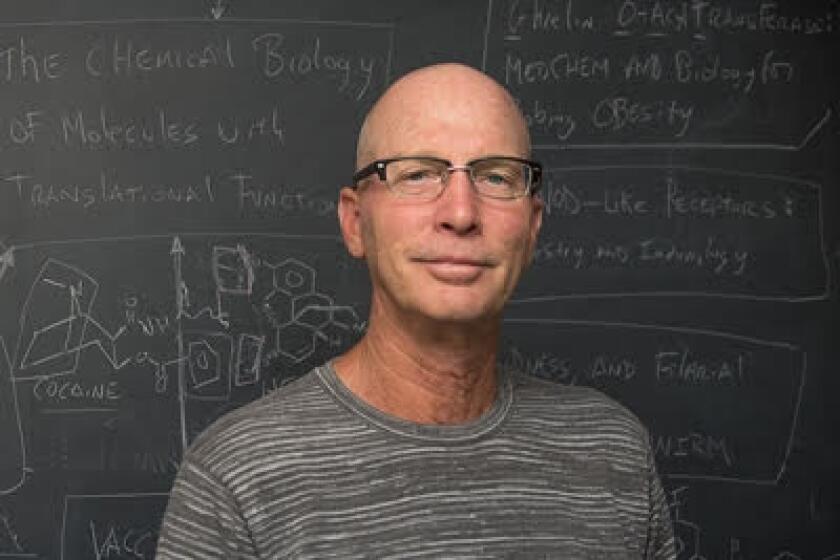

Put down that fork. You’re going to want to hear what Rob Knight has to say about the microbes in your gut before you consume another morsel of food.

Your ability to fight diseases like diabetes and to metabolize drugs may depend on it.

Knight is the prominent computational biologist that UC San Diego recruited earlier this year to help make the campus a leader in the study of the human microbiome.

The term refers to the genetic make-up of all of the micro-organisms that live in and on your body. Microbial genes far, far out number humans genes, and most microbes live in your gut.

There’s a rapidly growing belief in science that studying the microbiome can help identify a wide variety of diseases, and possibly help to treat or prevent sickness.

The 38 year-old Knight recently discussed how the field is evolving in discussions with the San Diego Union-Tribune.

Q: The microbiome has become a hot topic in science. What brought this about?

A: The technology for studying microbes got tremendously better. We went from using traditional techniques in chemistry, which were slow, to using fast sequencing machines that let us read out the DNA of huge numbers of microbes. That's what the sequencing technology from (San Diego’s) Illumina has done for us.

We also have been developing software programs that allow us to display and compare data. We can rapidly look for patterns. It's helping us to make sense of things.

Q: How much can scientists tell about a person's current health by looking at microbes?

A: We can tell the difference between people who have a disease and those who don't. There are good classification models for things like type 1 and type 2 diabetes and inflammatory bowel disease. You can't diagnose these diseases with 100 percent accuracy. But you can see differences between people.

We can also determine with 90 percent accuracy whether a person is lean or obese just by looking at their microbial genes. We can only do that with 58 percent accuracy by just looking at human genes.

We think we're going to be able to predict risk -- not just figure out if you're obese right now but whether you'll become obese, given some assumptions about your lifestyle. Ultimately, what we want to be able to do is reverse those conditions.

Q: Do you think it will be more valuable to sequence a person's microbes than sequence their human genes?

A: Yes. Sequencing your human genome tells you only about what genes you were born with. But sequencing your microbes can tell a lot about what you’ve picked up after that, from people you live, work and play with, and from the environment.

If you consider the amount of money that’s been spent on human genetic research, and the limited success in solving hard problems like obesity, it makes sense to look not just at the human genome, where we’re all over 99 percent the same as each other and we can’t make any changes, but also at the microbiome, where we can be 90 percent different from one another, and where we have all changed it profoundly during our lifetimes via processes we’re just beginning to understand.

Imagine if we could take control of those processes to shape our microbiomes for improved lifelong health.

Q: Can you see a broad number of diseases by looking at the microbes?

A: We're mostly talking about diseases associated with digestion and the immune system. Microbes are involved to a much greater degree than you might expect in diseases involving the neurological system, like multiple sclerosis, and psychological conditions like depression. We're trying to figure how well we can diagnose depression and autism by looking at the microbiome.

Q: Diagnosing depression can be very difficult. How does studying microbes help?

A: The microbiome has a lot of data in it. A single teaspoon of your stool has about as much data as one ton of DVDs. Scientists have found in studies of mice that microbes can actually cause depression. You also can change how anxious or brave a mouse is by swapping their gut microbes. There's a lot of things that gut microbes are involved in that no one knew about until very recently.

Q: But isn't a true that things you can do to a mouse don't necessarily work in humans?

A: Yes, I couldn't agree more. It's important not to give false hope. The role of the mouse model is to demonstrate biological possibility.

But it's important to study microbial genes, which vastly outnumber human genes. These microbial communities undergo profound change from the time a person is an infant until they're an adult. We’re changing them now in an undirected way, and they affect things like our metabolism and what chemicals are in our blood stream -- even the chemicals on our skin. If we can take control of that process, we could make a tremendous impact on our health.

Q: How would you take control? Are you talking about customizing drugs to people's microbiome?

A: Yes. We might be able to find out whether a drug like acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol, will be toxic to your liver, or whether heart drugs like digoxin or cancer drugs like cisplatin or cyclophosphamide will work for you or be degraded by your bacteria. These have all been demonstrated in research settings in different labs, but not yet validated in the clinic, which we need to do next.

GETTING TO KNOW THE MICROBIOME GETTING INVOLVED

The microbiome refers to the total genetic composition of all of the microbes that live in and on the human body. The microbes include bacteria, fungi, protozoa and viruses.

Scientists estimate that there are at least 100 times more microbial genes in a person’s body than human genes

Scientists have long known that bacteria in the microbiome helps people do everything from digest food to produce vitamins, including B12, thiamine, and Vitamin K, which is needed for blood coagulation.

But it wasn’t until the late 1990s that scientists came to broadly agree that the microbiome is important for human health.

The microbiome may weigh almost three pounds

Sources: NIH, University of Washington, UC San Diego

UC San Diego’s Rob Knight runs American Gut, a citizen-science project that’s meant to establish the microbial diversity of the human gut. People wishing to participate should go to americangut.org, where they can order a home sampling kit. Participants must provide a sample of their fecal matter. Knight says, “Most participants in the project support it by a contribution of $99, although more elaborate types of DNA sequencing and charitable contributions to support sequencing under-represented groups are also possible.”

One really exciting possibility is that if you don’t respond to a drug, you might be able to change your microbiome in a way that will make it useful for you. Lifestyle factors like how many kinds of plants you eat or whole grainsyou consume can have as big an effect on your microbiome as drugs or diseases. But we don’t yet know which of these things move you in the same directions.

Q: I could get my genome sequenced. But my doctor wouldn't know what to do with the information. That's broadly true among primacy care physicians. Do we face the same problem with the microbiome? Would most doctors know what to do with the information?

A: They don’t know yet. That’s why we need better efforts in medical education to tell doctors more not just about our human genome, but about our 'second genome' of millions of microbial genes. We also need better computer techniques to make the information easy to interpret, and more clinical research that targets different diseases so we can tell from your microbiome how your disease is progressing and whether your treatment is working.

This is why collaborations between doctors and software developers is so critical, and this is a key strength of the type of interdisciplinary research at UC San Diego. Remember, your cell phone has as much computer power as the fastest supercomputer on earth 30 years ago, but you didn’t have to cram a team of technicians into your pocket to keep it running, or even read a manual. So a lot of what we need to do is to make these systems easier to use rather than more powerful.

Q: If scientists are able to help people clearly visualize the information in their microbiome, would it lead people to change their diets? Would fewer people become sick?

A: Yes, absolutely. If you wear a Fitbit, you'll know that it sort of nags you if you don't walk enough. The same kind of thing would happen if you got information about your microbiome. You would know whether you're doing well or not based on things like your diet and your lifestyle.

Q: How would people get this sort of information?

A: I think we'll be able to develop 'smart toilets" that take samples of your stool and analyze it so that know what's going on inside your gut. The toilets would do some type of chemical or DNA analysis every time your flush .That way, the incredible data in your stool wouldn't be flushed down the toilet. A smart toilet would tell you things like, 'Today, this is how much harm you did to your micobiome,' or, "On this day, you did this much good.' I think this could really be transformative.

Q: Would this be a toilet used only by people who were older?

A: No, it would be for people of all ages. The gut microbiome in infants has been linked to all sorts of things, like asthma, allergies, and obesity. If you could get real-time feed back, you could find out things like whether a one-year-old was at risk for developing asthma. We're going to get to the point where we can build computer models that reveal whether your bacteria is pro-inflammatory, which can cause problems, or anti-inflammatory. There will be all kinds of interventions. And for young children, it’s really easy to get the stool from diapers, which you have to handle anyway as a parent.

It's going to seem silly, I know. But James Lind's efforts in the 1700s to squeeze lemon juice and give it to his crew probably seemed silly, too. But it eliminated scurvy, which used to kill the majority of sailors on many long ocean voyages.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.