CANCER

Where are we

The fight against cancer has proved to be one of the greatest intellectual and practical challenges of modern times. A hundred years ago, surgical interventions backed by early forms of radiation therapy were the only weapons at the disposal of doctors. Since then, a number of key revolutions have changed that.

The first was the introduction of chemotherapy, in the form of drugs that were derived, ironically, from the mustard gas which was used as a weapon during the first world war. Doctors who carried out autopsies on gas victims noted that it inhibited cell division, and developed versions that helped to stop tumour cells from proliferating. These became routine treatments in the 1950s.

What now?

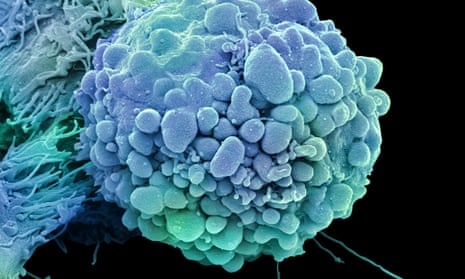

As genomic research progressed in the 20th century, scientists have used that knowledge to develop new treatments. Recent advances have included targeted therapies. These are more specific in their action against tumours because they act on molecular targets associated with particular cancer cells, whereas most standard chemotherapies act on all rapidly dividing cells, be they normal or cancerous.

For example, in about one in five breast cancer patients, tumour cells have too much of a growth-promoting protein known as HER2 on their surface. Breast cancers with too much of this protein are particularly aggressive, scientists found. A number of drugs, such as Herceptin, have been developed to target this protein and block the spread of tumour cells. These targeted therapies are now a mainstay in the battle against cancer.

What are the major problems?

Great progress is being made, but the emerging problem may be financial rather than technical. The new generation of drugs being developed are very expensive, raising questions of affordability.

Take the fledgling technology of immunotherapy. Cancer cells possess a sort of secret handshake that persuades T-cells, a key part of the body’s anti-disease defences, not to attack them. In the 1990s, scientists discovered a molecule on T-cells that was part of this handshake. It is known as programmed death 1 (PD1) and, since its discovery, researchers have been trying to disrupt its function.

The new drugs unveiled in Chicago last week are the result of this work. Trials on patients with advanced melanoma, which has a high death rate, have already produced encouraging results, but scientists warn that there could be serious side-effects in some patients.

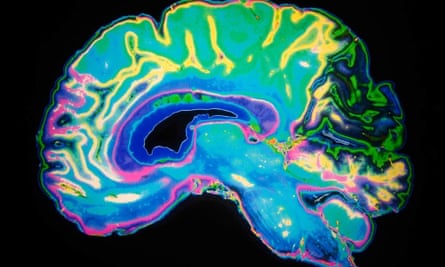

DEMENTIA

Where are we?

Dementia is not actually a disease. It is the outcome of many different conditions. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common of these but others include vascular dementia and frontotemporal dementia. All of these forms share common symptoms, however. These include memory loss, confusion and personality change.

While dementia is certainly not an inevitable outcome of getting old, the likelihood of developing the condition undoubtedly increases with age. Thus, as infectious diseases were vanquished in the UK, and mortality rates for cancer and heart conditions forced down, more and more people have been able to live to old age. (Life expectancy in the UK is now 79 for men and 83 for women.)

Today, it is calculated that there are now more than 850,000 people with dementia in the UK.

What now?

By 2025, the number of cases of dementia in the UK is expected to rise to more than 1 million. By 2050, it is projected to exceed 2 million. In addition, the condition has been found to be particularly common in women. Of the 850,000 dementia patients in Britain, 500,000 are female. As a result, women over 60 are now twice as likely to get dementia as breast cancer.

Scientists are now working on ways to use genetic and stem-cell technologies to understand the detailed causes of the various forms of dementia and, in the long run, to develop drugs that could slow down the loss of faculties in those affected by the condition.

Scientists caution that this aspiration remains a long-term goal and warn there is much work that still needs to be done.

What are the problems?

A key problem for those trying to tackle dementia is a lack of resources. There have been major investments in heart disease and cancer research in recent years and these have helped bring down death rates.

But that has not happened with dementia, said Matthew Norton, head of policy for Alzheimer’s Research UK. “Just look at the figures,” he said.

“Total spend in the UK - from charities and the government - on dementia in 2013 was £73.8m. By contrast, for cancer, that figure was £503m.” This underfunding means reduced manpower, say campaigners. There are some 3,600 dementia researchers working in the UK –about 19,000 fewer than those working on cancer, even though dementia costs the UK economy more. So, prospects of finding treatments to slow or halt the loss of faculties associated with dementia will be limited, say researchers.

HEART DISEASE

Where are we?

Over the past 50 years, there has been an impressive improvement in mortality rates from cardiovascular disease in Britain. This point was precisely summed up by Peter Weissberg, medical director of the British Heart Foundation. “The foundation was established in 1961, when heart disease was ravaging the country. It caused nearly half of all deaths in the UK in that year.”

With hindsight, it is not hard to see why. Smoking levels were four times higher than today, while eating foods high in saturated fats - whole milk, butter and red meat - was the norm.

Today, those foods have been replaced by lower-fat options, vegetable oils, skimmed milk and poultry. We have medicines to reduce blood pressure and cholesterol levels, and it is possible to open blocked or narrowed arteries without major surgery.

What now?

Devising drugs to treat damaged hearts suffers from a key problem: they are difficult to test. “We cannot keep cutting patients open to remove heart-tissue samples. That is just not practical or ethical,” said Chris Denning of Nottingham University.

A solution for scientists in recent years has been to turn to the use of stem cells. At Nottingham University researchers have taken cells from patients’ skin and bathed them in nutrients in order to transform them into stem cells, a type of cell that can be turned into any tissue. These cells are then developed into heart cells, which are kept in Petri dishes for testing purposes.

“That means they are ideal for trying new drugs on. It is an incredibly important development,” added Denning.

Other scientists believe that it may be possible to use stem cells to directly repair, damaged hearts in the near future.

What are the problems?

Although medical procedures continue to improve prospects for saving the lives of those who suffer from cardiovascular disease, there are a host of epidemiological issues that threaten to offset these benefits.

For example, the rate of smoking declined sharply between 1972 and 1994 but the fall-off has since slowed down. And the prevalence of heavy drinking has not changed substantially since the 1970s. Worse, childhood obesity has been increasing in both boys and girls since the mid-1980s, while adult obesity rates are also continuing to rise – as is the incidence of diabetes in the UK. All these factors increase the risk that heart disease mortality rates could rise again in the near future.

Weissberg has warned that these factors “threaten to derail the decreasing trends in heart disease and death rates that we are now experiencing”.

INFECTIOUS DISEASE

Where are we?

Defeating the scourge of infectious disease in the western world is generally attributed to the development of vaccine programmes and antibiotics, although improved sanitation and health education have also been key factors.

“In fact, death rates from tuberculosis, a pernicious killer, had begun to drop by the mid-19th century,” said Carsten Timmermann of Manchester University. “In 1838, there were around 4,000 deaths per million as a result of TB, but this had dropped to around 1,000 by 1900. Vaccines and antibiotics had nothing to do with that. Indeed, it is not clear why the decline occurred at all. But it is also evident that programmes such as the BCG vaccine project had really stopped tuberculosis being a serious killer by the middle of the 20th century.”

What now?

In the west, most infectious diseases are now kept at bay. However, the balance is an uneasy one. “In the 1960s, a US surgeon-general was alleged to have claimed that infectious diseases had been completely defeated,” said Jeremy Farrar, who is head of the UK Wellcome Trust.

“The story may be apocryphal but it certainly sums up attitudes at the time. Then, a couple of decades later, we had the arrival of HIV in the west and a very clear lesson about the ever-present danger of infectious diseases, which can spread very quickly from other parts of the world.”

In addition, the rise of antibiotic resistance - a result, in part, of overuse - has led to growing fears that one of the west’s key defences against infectious disease may be lost in the near future, unless pharmaceutical companies speed up the development of new versions.

What are the problems?

In an increasingly connected world, it’s more and more difficult to contain infectious diseases. Changes in weather patterns and increased migrations from areas affected by rising sea levels or spreading deserts will also intensify the risk of new diseases or new strains of existing conditions arriving in the west.

“In developing nations, we have replaced the problems of infectious disease with health issues such as diabetes and obesity,” said Farrar. “But in developing nations, they still have major problems with infectious diseases - malaria, TB and HIV, for example - but are also being affected by obesity and diabetes. Countries such as these - Vietnam is a good example - need considerable help from global agencies such as the World Health Organisation. However, these agencies are not getting the support they need from the west any more.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion