Here's the Best Thing the U.S. Has Done in Afghanistan

With the help of foreign aid, the public healthcare system has vastly improved the Afghan life expectancy.

While the U.S. military can win wars with overwhelming firepower, the conventional wisdom is that the U.S. lacks effective civilian tools to win the peace. Afghanistan's public health care system provides a powerful counterpoint: financed largely by American foreign aid, it has produced the most rapid increase in life expectancy observed anywhere on the planet. What went right? And why do American auditors and Congressional overseers suddenly want to pull the plug?

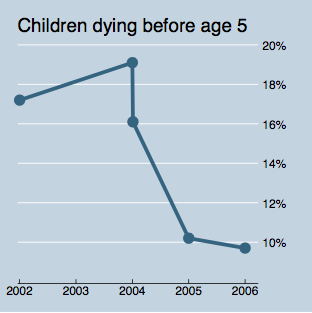

In late 2011, the U.S. Agency for International Development announced some astonishing news about progress in health and mortality in Afghanistan. The new findings came from the release of the 2010 Afghanistan Mortality Survey, the largest survey of its kind ever undertaken in Afghanistan. The survey showed that from 2004 to 2010, life expectancy had risen from just 42 years--the second lowest rate in the world--to 62 years, driven by a sharp decline in child mortality. As a result, nearly 100,000 Afghan children per year who previously would have died now don't.

In terms of lives saved, it is as if the entire Syrian tragedy were averted thanks to a U.S. aid program few Americans had ever heard of.

This accomplishment was not just a victory for "aid," generically. Afghanistan's progress against mortality reflects the particular success of a way of doing aid in the health sector that differed dramatically from the amateurish, militarized, and externally imposed modus operandi of the bulk of American aid to Afghanistan during the war.

"Winning hearts and minds" has been the informal rallying cry for the majority of our aid efforts in the country. As money poured into country in 2003, aid projects largely ignored the poorest areas and instead targeted hotspots of insurgent activity. Aid workers took orders from military commanders who erred toward making a visible splash rather than a long-term impact. Not only did these projects build schools and clinics without budgeting for teachers or nurses, in the case of two schools in southern Afghanistan--an area of frequent seismic activity--U.S. auditors found military contractors had built walls so flimsy they couldn't support the schools' concrete roofs.

Afghanistan's health program bucked this trend toward "quick impact, quick collapse" projects, as aid workers mockingly called them. Rather than going it alone, the U.S. teamed up with European donors and the World Bank in a multilateral effort. And rather than cutting sweetheart deals with American military contractors, the health program was coordinated by the Afghan government's own Ministry of Public Health. Most radical of all, the program focused on measureable results, commissioning an independent evaluation by a team from the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health.

By the end of Taliban rule in 2002, Afghanistan's public health system had collapsed. To begin to resuscitate it, aid donors and the Afghan government devised a basic package of health services that cost about $4.50 per person. Recognizing the government's limited reach in many provinces, they contracted national and international NGOs to help them deliver this basic package of services across 90% of the country. From 2004 to 2010, the Johns Hopkins team found that in the typical Afghan district, the share of clinics meeting minimum staffing levels had risen from roughly 40% to nearly 90%, and the proportion who met their annual target of at least 750 new outpatient visits rose from around 20% to over 80%. As a result, access to basic services like vaccination and family planning advice was way up.

Despite these successes, the health program has met resistance from an unexpected source: auditors.

***

John Sopko is the U.S. government's chief auditor for Afghanistan and a former prosecutor with years of experience on Capitol Hill. In September, Sopko's office--the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, or SIGAR--issued a report calling for the suspension of USAID's $236 million in aid for basic health care in Afghanistan.

Why shut down such a successful program? The short answer is that SIGAR's is a peculiar concept of caution.

Strikingly, the auditors' report calling for the funding freeze for the health program doesn't claim any evidence of serious fraud or waste. Instead, it raises hypothetical concerns about the Afghan government's ability to manage aid money well, including evidence that some salaries were paid in cash, as well as the absence of double entry bookkeeping.

While the U.S. military can produce receipts for bombs and bullets bought in America, the Afghan government struggles to do the same for vaccines dispensed in remote rural clinics. Thus, from a government auditor's perspective, it is riskier to give Afghan citizens health care than to shoot their insurgents.

Sopko had already appealed to Congress to reconsider future aid to the Afghan government. Over the summer, the SIGAR public affairs office launched an accompanying media blitz, complete with a New York Times editorial expressing grave concern over "lapses in accountability," and a Twitter account tweeting mundane ways in which U.S. agencies are failing: "State Dept. never finalized draft 2010 U.S. anti-corruption strategy for #Afghanistan," or "USAID could not provide documentation showing methodology used to calculate $236M program cost estimate." This outreach culminated with a publicity stunt demanding that State Department, Pentagon, and USAID officials engage in public self-criticism by nominating a top 10 list of their own worst aid projects.

Unsurprisingly, Sopko's anti-government spending campaign caught the attention of Tea Party members in Congress, who took up his talking points that giving money to Afghanistan was simply too risky. Notably, the concept of risk used here is completely unrelated to the 20% risk of death before age five faced by Afghan children as of 2004; a risk which has declined by half with the help of American aid.

***

Since 2001, USAID has been called on to assist U.S. military efforts in Iraq, Afghanistan and beyond, as the softer side of a counter-insurgency strategy. And aid has shared the blame for the failure of that strategy. "President Obama's strategy depended upon the civilian experts at USAID making smart decisions to help the Afghans," writes the Washington Post's Rajiv Chandrasekaran in his book on the Obama administration's surge in Afghanistan. "But the agency kept making mistakes ... The result was a gross failure to capitalize on security improvements, paid for by the lives and limbs of American troops."

Aid will never be a substitute for a military strategy. Aid is not a counter-terrorism policy. But the lesson of USAID in Afghanistan is not that help is futile; on the contrary. When America gives aid for the sake of saving lives rather than winning hearts and minds, it can be incredibly effective, even in the inauspicious conditions of rural Afghanistan.

Beyond hunting Osama Bin Laden to make America safer, American leaders have sold the war in Afghanistan in lofty terms, as an altruistic fight for the benefit of Afghan women and children terrorized under Taliban rule. When presented with the means and the opportunity to save the lives of thousands of those very same mothers and infants, if America retreats on the grounds of procurement rules and auditing queries, this narrative becomes hard to maintain.

Disclosure: The author's brother is a legal advisor to the USAID Office of the General Counsel, previously posted to Kabul, where he provided legal counsel to the mission in general and had no policy or programmatic role in the health program.