Chinese government propaganda is often pretty heavy-handed. State media insist that economic growth will be L-shaped, for example, but do not bother to say what that means. A string of bizarre English-language music videos demand praise for China’s 13th Five-year Plan, and detail how great Americans find it to work for a Chinese boss.

But these examples follow a 20th-century template for propaganda, in which a dominant organization—in this case, the Chinese Communist Party—disseminates its message to the public at large. Thanks to the internet, though, this one-to-many propaganda is less effective than it used to be. Top-down party-produced messages are frequently ridiculed within China, and directives openly questioned, now that people have an opportunity to respond online.

The party has therefore had to develop subtler ways of controlling its message online. A new study reveals just how this works.

Researchers analyzed tens of thousands of posts to Chinese social media and internet forums, extracted from hacked emails obtained from the propaganda department of Ganzhou, a city in southeast China. The posts come from internet mercenaries paid by the government to spread certain kinds of messages online. These commenters are widely known as as the wumao dang, or “50-cent party,” a reference to a 2010 editorial in the state-run Global Times that said commenters are paid 50 cents renminbi per post.

The hacked emails, which include propaganda directives sent from the department to wumao, as well as summaries of posts made by these individuals, were released at the end of 2014. At that time we did our own analysis of the propaganda effort around a single televised interview with Ganzhou’s local party chief. This event was revealing, but ultimately anecdotal.

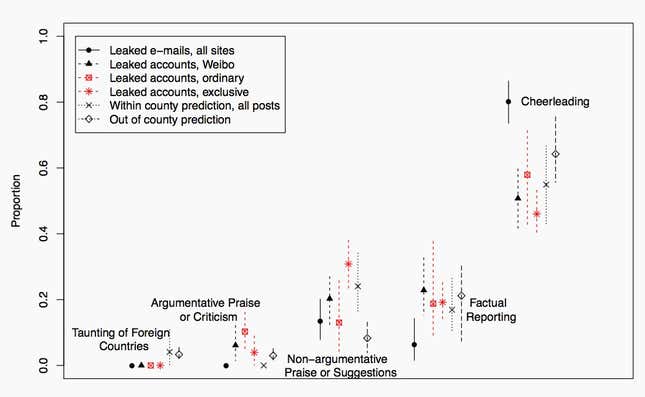

The researchers, however, systematically sorted all of the posts into five categories and identified the kinds of messages that wumao are paid to spread. The most common category by far is “cheerleading,” general enthusiasm about the job the Communist Party is doing or about life in general, like ”Party Secretary Shi is an exemplary Party Secretary!” or “Way to go Ganzhou!” Yet almost no posts fell into the categories “taunting of foreign countries” or “argumentative praise or criticism.” The remaining two categories—”non-argumentative praise or suggestions” and “factual reporting”—also had relatively few posts.

Here is a chart of their findings:

This breakdown says a lot about how the internet works in China.

For one thing, it shows the subtlety of the party’s strategy for manipulating the many-to-many conversations that are happening online. This strategy aims to, as the study’s authors write, “actively distract and redirect public attention from ongoing criticism, other grievances, or collective action.” The party’s goal is not to inspire deep love of China or hatred for its enemies. It instead aims to prevent, or at least break up, any widespread anti-party consensus among the public.

Here’s an example of how this works. Many of the wumao posts that appeared on social media and forums during the televised interview in Ganzhou were clearly taken straight from the propaganda department’s directive. The same few “cheerleader” messages were posted dozens of times, verbatim, on the same platforms. Most readers probably know that these come from wumao, but their volume alone gets in the way of meaningful discussion of deeper issues. What’s more, they might appear alongside other positive but less obviously wumao posts, causing confusion over just how real that sentiment is.

This is similar to how the party approaches censorship online. One-off critical comments are normally left alone, but consistently anti-party memes, news stories, or individuals are comprehensively scrubbed from the internet. People are allowed to express their own particular grievances so long as they don’t align with those of others.

The study also reveals the uneasy relationship between the party and the ultra-nationalists that regularly rear their heads on the Chinese internet. Aggressively pro-China, anti-Japan, anti-democracy commenters are part of the furniture online. The most prominent group of Chinese cyber-nationalists, Di Ba, recently leapt over the Great Firewall in order to spam the Facebook page of Taiwan’s incoming president, Tsai Ing-wen, with anti-Taiwan comments and memes, and blast a live-feed of her inauguration with rocket emoji. But if the category breakdown of wumao posts from Ganzhou holds true for the rest of the country, these nationalists who “taunt foreign countries” are not paid for by the government, and are acting on their own.

Since the party is not paying them, it is either passively supporting them by allowing them to exist, or scared of shutting them down. While the nationalist message is frequently in line with that of the party, the group is in fact capable of posing a broader threat if it feels that liberal reformers are starting to hold too much sway. A combination of these dynamics led to the nationalist support for Bo Xilai—a prominent leader who embraced a kind of Maoist-Nationalist message—and his eventual rejection from the party. Criticism can come from the left and the right, and the party fears both.

With the advent of the internet, the top-down era of party propaganda—with ”red songs” written by the party and sung country-wide, or of insistence on using ”comrade” to greet anyone and everyone—is over. But the propaganda departments of Xi Jinping’s China have found a way to stay just as relevant as ever.