Ever since Charles Babbage’s conceptual, unrealised Analytical Engine in the 1830s, computer science has been trying very hard to race ahead of its time. Particularly over the last 75 years, there have been many astounding developments – the first electronic programmable computer, the first integrated circuit computer, the first microprocessor. But the next anticipated step may be the most revolutionary of all.

The Guardian’s product and service reviews are independent and are in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative. We will earn a commission from the retailer if you buy something through an affiliate link. Learn more.

Quantum computing is the technology that many scientists, entrepreneurs and big businesses expect to provide a, well, quantum leap into the future. If you’ve never heard of it there’s a helpful video doing the social media rounds that’s got a couple of million hits on YouTube. It features the Canadian prime minister, Justin Trudeau, detailing exactly what quantum computing means.

Trudeau was on a recent visit to the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Waterloo, Ontario, one of the world’s leading centres for the study of the field. During a press conference there, a reporter asked him, half-jokingly, to explain quantum computing.

Quantum mechanics is a conceptually counterintuitive area of science that has baffled some of the finest minds – as Albert Einstein said “God does not play dice with the universe” – so it’s not something you expect to hear politicians holding forth on. Throw it into the context of computing and let’s just say you could easily make Zac Goldsmith look like an expert on Bollywood. But Trudeau rose to the challenge and gave what many science observers thought was a textbook example of how to explain a complex idea in a simple way.

The concept of quantum computing is relatively new, dating back to ideas put forward in the early 1980s by the late Richard Feynman, the brilliant American theoretical physicist and Nobel laureate. He conceptualised the possible improvements in speed that might be achieved with a quantum computer. But theoretical physics, while a necessary first step, leaves the real brainwork to practical application.

With normal computers, or classical computers as they’re now called, there are only two options – on and off – for processing information. A computer “bit”, the smallest unit into which all information is broken down, is either a “1” or a “0”. And the computational power of a normal computer is dependent on the number of binary transistors – tiny power switches – that are contained within its microprocessor.

Back in 1971 the first Intel processor was made up of 2,300 transistors. Intel now produce microprocessors with more than 5bn transistors. However, they’re still limited by their simple binary options. But as Trudeau explained, with quantum computers the bits, or “qubits” as they are known, afford far more options owing to the uncertainty of their physical state.

In the mysterious subatomic realm of quantum physics, particles can act like waves, so that they can be particle or wave or particle and wave. This is what’s known in quantum mechanics as superposition. As a result of superposition a qubit can be a 0 or 1 or 0 and 1. That means it can perform two equations at the same time. Two qubits can perform four equations. And three qubits can perform eight, and so on in an exponential expansion. That leads to some inconceivably large numbers, not to mention some mind-boggling working concepts.

In artificial intelligence and cryptography, it’s thought that quantum computing will transform the landscape

At the moment those concepts are closest to entering reality in an unfashionable suburb in the south-west corner of Trudeau’s homeland.

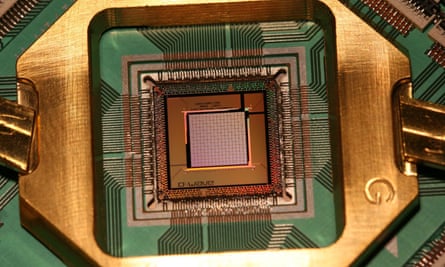

In a neat, spacious lab in Burnaby, a satellite of Vancouver, I’m looking inside what appears to be a large black fridge about 10 feet high. Within it is an elaborate structure of circuit boards, not unlike the sort of thing a physics class might construct out of Meccano, except with beautifully colourful niobium wafers as the centrepiece. It all looks fairly unremarkable, yet somewhere in here a multiplicity of different universes are thought to exist.

The lab belongs to a small company called D-Wave, a highly skilled collection of just 140 employees that prides itself on building the world’s first functioning quantum computer, which is what is contained within the large fridge-like casing. Actually it is a fridge, the coldest fridge ever assembled. The cooling apparatus enables the niobium computer chip at its core to function at a temperature of just under –273C, or as close to absolute zero as the known universe gets.

The supercooled environment is necessary to maintain coherent quantum activity of superposition and entanglement, the state in which particles begin to interact – again rather mysteriously – co-dependently, and the qubits are linked by quantum mechanics regardless of their position in space. Any intrusion of heat or light would corrupt the process and thus the effectiveness of the computer.

Exactly how and why quantum physics adheres to these science-fiction like rules remains an issue of great speculation, but perhaps the most common theory is that the different quantum states exist in separate universes. The D-Wave quantum computer I look at has one thousand qubits.

“A thousand qubit computer can be in 2 to the 1,000 states at one time, which is 10 to the 300th power,” says D-Wave’s CEO, Vern Brownell. “There’s only 10 to the 80th atoms in the universe. Now does this mean it’s in 10 to the 300th universes at the same time?”

Can billions of different universes coexist within one computer? That’s the sort of question that is probably best not grappled with before midnight and without the aid of illegal stimulants. And in a sense, the answer doesn’t matter. The more immediate and relevant question is whether or not this quantum computer works.

At the moment quantum computing still resides within a largely theoretical or speculative realm. The potential is staggering, involving a computational power many times the order of all the world’s existing classical computers combined. But realising that potential is a fiendishly difficult task.

That’s why D-Wave’s 2X computer costs more than $15m and only a handful of organisations have so far bought one. Still, as those organisations include Google, Lockheed Martin and Nasa, and among D-Wave’s investors are Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and the CIA’s hi-tech arm, In-Q-Tel, it’s clear that some of the world’s most forward- looking institutions believe that the computer has a future.

In areas such as artificial intelligence and cryptography, it’s thought that quantum computing will transform the landscape, perhaps bringing about the breakthrough that will enable machines to “think” with the nuance and interpretative skill of humans.

Brownell used to be chief of technology at Goldman Sachs. In that job there were few tech developments that he didn’t have pitched at him. He believes that while social media successes like Facebook are clever utilisations of existing technology, the fact that Silicon Valley is constantly chasing profitable variations on the same theme means that it is no longer doing the really tough mental work. “The level of innovation is much, much less than we’ve seen historically and probably at an all-time low in terms of the real world-changing innovations.”

D-Wave, he says, boldly bucks this trend. But that’s not how he used to think. When he first heard about D-Wave seven years ago, the company had been going for nine years and, in some informed circles, was a bit of a laughing stock. His initial reaction when the company approached him was deep scepticism.

“I didn’t believe it at first at all,” he says, “particularly as there were all these blog comments with experts saying it was snake oil. I wasn’t really interested.”

His attitude changed when he came out and met the team. D-Wave was co-founded by Geordie Rose, a 44-year-old physics PhD who, doubtful about academia, took a course in entrepreneurship. He was impatient with the research approach of highly expensive but severely limited laboratory experiments.

Rose’s novel idea was to build a functioning quantum computer with commercial appeal. But this is where the science starts to cause people to pull their hair out. Most experimental quantum computers that had been assembled in labs followed the universal gate model, in which qubits substituted for transistors, without any notable success.

Rose chose instead to develop an “adiabatic” quantum computer, which works by a process of what’s called “quantum annealing” or “tunnelling”. In essence, it means you develop an algorithm that assigns specific interactions between the qubits along the lines of the classical model – ie if this is a 0, that one is 1 etc. Then create the conditions for quantum superposition, in which the qubits can realise their near infinite possibilities, before returning them to the classical state of 0s and 1s. The idea is the qubits will follow the path of least energy in relation to the algorithmic requirements, thus finding the most efficient answer.

If that’s hard enough to explain, imagine how difficult it was to build. And the early results were not encouraging. No one seemed to be sure what, if anything, was going on at a quantum level, but whatever it was, it wasn’t impressive.

D-Wave’s first demonstration in 2007 of its 16-qubit device, which involved solving a sudoku puzzle, hardly set the world on fire. Umesh Vazirani, co-author of a paper on quantum complexity theory, dismissed D-Wave’s claims of speedup as a misunderstanding of his work, and suggested that “even if it turns out to be a true quantum computer, and even if it could be scaled to thousands of qubits, [it] would likely not be more powerful than a cellphone”.

Even if no one ever builds a useful quantum computer we still learn an immense amount by attempting to

Thereafter the company was regularly accused of hype and exaggeration. Part of the problem was that it was very hard to measure with any agreed accuracy what was happening. D-Wave came up with a test to show that entanglement – seen as a necessary prerequisite for a working quantum computer – was taking place.

But some experts doubted the reliability of the test. When D-Wave passed a different test, developed by an independent scientist, sceptics argued that while entanglement might be happening, the only real test was performance.

In 2013, the D-Wave Two was cited in one test as performing 3,600 times faster than a classical computer. But yet again these results were rubbished by several prominent scientists in the field. In 2014 Matthias Troyer, a renowned professor of computational physics, published a report that stated that he found “no evidence of quantum speedup”.

A longtime doubter of D-Wave’s claims is Scott Aaronson, a professor at MIT, who has called himself “Chief D-Wave Sceptic”. After Troyer’s paper, he argued that although quantum effects were probably taking place in D-Wave’s devices, there was no reason to believe they played a causal role or that they were faster than a classical computer.

Brownell is dismissive of these critics, claiming that the “question has been largely settled”. He cites Google’s comparative test last year in which its D-Wave quantum computer solved certain problems 100m times faster than a classical computer.

“If it isn’t quantum computing,” asks Brownell, “then how did we build something that’s a hundred million times faster than an Intel Core? It either has to be quantum computing or some other law of nature that we haven’t discovered yet that’s even more exciting than quantum mechanics. I challenge any scientist in the world to tell us: if it’s not quantum annealing, what is it?”

Even Aaronson acknowledged that the Google test was significant. “This is certainly the most impressive demonstration so far of the D-Wave machine’s capabilities. And yet,” he added, “it remains totally unclear whether you can get to what I’d consider ‘true quantum speedup’ using D-Wave’s architecture.”

But Troyer was not convinced. “You need to read the fine print,” he said. “This is 108 times faster than some specific classical algorithm on problems designed to be very hard for that algorithm but easy for D-Wave… A claim of 108 speedup is thus very misleading.”

One side-benefit of all these claims and counter-claims, as Aaronson has most forcefully argued, is that they help us to understand quantum mechanics a little better. Nic Harrigan works at the Centre for Quantum Photonics at Bristol University, a leading research institute in quantum mechanics.

“Although there are incredible potential applications of quantum computing,” Harrigan says, “even if no one ever builds a useful quantum computer we still learn an immense amount by attempting to. This might sound like ass-covering, but quantum mechanics itself is a theory so fundamental to our understanding of the universe, and is the seed to so many current and future other technologies, that anything we can do to understand it better is huge. Somewhat incredibly it turns out that a good way to try and understand what is actually going on in quantum mechanics (and just how it differs from normal classical physics) is to consider which kind of computational problems one can more easily solve using quantum mechanical systems.”

At Google they were cautiously optimistic about D-Wave’s usefulness. The head of engineering, Hartmut Neven, outlined the strengths and weaknesses of the tests, and acknowledged that while there were other algorithms that, if deployed on classical computers, could outperform quantum annealing, he expected future developments to favour quantum annealing. “The design of next-generation annealers must facilitate the embedding of problems of practical relevance,” he said.

The kinds of problems that quantum annealing might help address are all concerned with what’s called optimisation – finding the most efficient model in complex systems.

“Optimisation sounds like a really boring problem,” says Brownell, “but it’s at the core of so many complex application problems in every discipline. Probably one of the most exciting is in the artificial intelligence world. Say you’re trying to recognise a water bottle. It still takes computers an enormous amount of time to do that not as well as humans do. Computers are catching up, but quantum computing can help accelerate that process.”

He cites genomics, economics and medicine as other areas that are rich with optimisation problems. With conventional computers, creating complex models – such as, for example, the Monte Carlo simulation used in the finance industry to analyse different interest rate scenarios – requires an enormous amount of computing power. And computing power requires real power.

“You go to these big web properties and they have data centres that are installed next to hydroelectric plants because they consume so much electricity,” says Brownell. “They’re the second-largest consumers of electrical energy on the planet.”

D-Wave’s vision, he says, is for a green revolution in computing, in which everyone will have access to much more energy-efficient quantum computers through the cloud. In a few years, he thinks, we’ll be able to access quantum computing from our phones.

“I think we have the opportunity to create one of the most valuable technology companies in history,” says Brownell. “I know that sounds really grand, but based on the capability we’ve built, we’re at the stage to be the dominant player in quantum computing for decades to come.”

Well, any self-respecting CEO would say that. But it certainly seems that D-Wave are currently leading the quantum computer race. Where that race is going, what it involves and how many universes it’s taking place in are, however, questions that we’ll probably need a working quantum computer to answer.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion