Somehow I had relegated Alexander Calder to a world of old New Yorker cartoons, with twangly mobiles dangling over the trust-fund infant’s cot, and brightly-coloured steel sculptures lending a joshing, lumbering air to windswept corporate plazas. Calder’s datedness felt like a future we no longer believe in. Then along comes Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture at Tate Modern. What a surprise and a delight the exhibition is: both a reminder of how good he could be, and a revelation of how complex and far-reaching his influence still is.

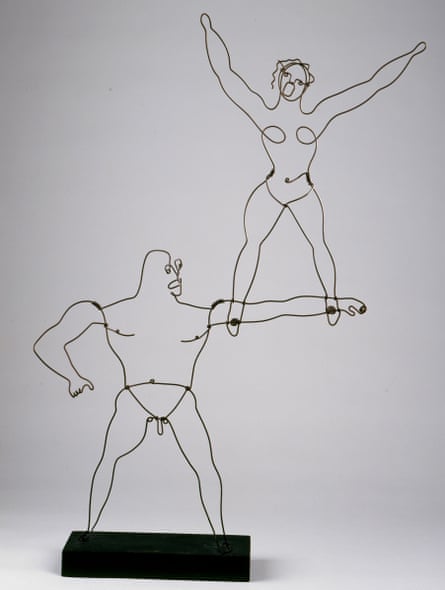

Calder shuttled between the US and Europe between the wars, making friends and carrying his miniature, mechanised travelling Circus with him; starting work on it in 1926, he continued developing it until the 1960s. Film of Calder performing with his cast of little sculpted high-wire acrobats and strongmen is shown, irritatingly, on a small screen, but it is surrounded by a selection of props and handbills and by a joyous selection of cobbled together wire sculptures and portraits. These are both drawing and sculpture, funny, at times lewd (there are lots of little willies and wiry armpit hair ) and deliciously playful.

Among the wire elephants, horses, a bullfighter and a dog, portraits twisted and bent from wire hang from the wall: composer Edgard Varèse with his scribbly eyebrows, Joan Miró, with sticky-out ears, dancer Josephine Baker with spiralling wire breasts and funny feet. All these could look like a party trick, were it not for their tenderness and energy, a liveliness that makes them more than caricature. Each sculpture is a kind of impromptu performance in its making, but Calder’s sculpture went on to perform in its own right, beginning with suspended elements in the early 1930s.

Visiting Mondrian’s studio in 1930, Calder suggested that the Dutch abstractionist might set the little coloured squares and rectangles he had pasted on his wall in motion, by the use of some motorised device. Mondrian disagreed, but Calder went away and set about making a number of motorised abstractions of his own. Most are too fragile to be set in motion any more, but they in turn led to a sculptural arrangement that fills a room of its own. A number of wine bottles, a wooden crate, a toy gong and an empty tin can sit on the floor. Hovering overhead is a suspended armature, from which hangs a heavy red ball at one end, and a small white ball from the other.

Visiting the show before the opening, I watched Sandy Calder, grandson of the artist, poke the red ball with a padded stick, setting it slowly swinging. The armature sways and turns and the smaller ball goes mad, swinging wildly between the objects below, occasionally colliding with them. The white ball hits the tin can, makes an orbit of the wooden box, just misses a small toy gong, careens into a wine bottle and wanders off on further eccentric orbits.

Sadly, visitors to the show won’t experience this exercise in beautiful futility. A gallery sign also tells us neither to blow on Calder’s mobile sculptures, nor to touch them, though they tempt us just by their presence, the delicacy of their dynamic balance and suspension. They could almost be set in motion by power of thought alone, just by looking at them.

Sitting in the large, open space at the centre of the exhibition – surrounded by Calder’s Mobiles (the name was suggested by Marcel Duchamp), hovering overhead, rising from the floor, hanging before the translucent window blind and ranged around the walls – you feel as if you are at the still centre of the universe in motion around you. A selection of works from the early 1930s to 1961 slowly turn and sway in the air currents generated by the movement and warmth of human bodies, as well as the gallery’s climate control system. As one turning sculpture paddles the air, the air quivers with it. Who knows where the chain reaction ends?

As the sculptures move, they slow you right down. It is best, if you can, to stay still. The finest of Calder’s works – and his mobiles were the best of what he made in his long career – need few words or explanations. At first, it is enough to be with them, watching them turn and dip and rise, performing their slow, balletic orbits. Ignore one of them for a bit and, when you look again, something has changed. You become sensitised to their constant self-adjustments. The weightless, gently animated pleasures of Calder’s mobiles are atavistic: like the pleasure of watching snow flurry around a streetlight, a flock of birds turning in flight, the last few autumn leaves flickering in the wind, constellations hammering the night sky.

The variety is enormous, though the principle remains the same. The sculptures shiver with light, turn like sentences in the mind. With their conflations of little dangling shapes, their blob shapes and ovoids and flights of coloured chevrons, their black and white discs and sometimes curlicued armatures, they approach a kind of unknown language written in space, indecipherable messages from alien civilisations.

Whatever else they are, or whatever they allude to (plant life, shoals of fish, stars and so on), they have a palpably benign, generative air. Calder’s sculptures dance together and alone, talk to one another, occupy the same space as us, are displaced by our presence. Sometimes – you can feel it – their heaviness and density resist movement. At other times they move not with us, but to us. You don’t so much look at them as watch them.

Calder’s mobiles have a lovely sense of rightness and tactile fabrication, a great sense of composition and poise. They are made to give pleasure. They don’t threaten as a Giacometti surrealist sculpture does or baffle us in the way Duchamp did. So many artists have hung things from strings and set the world spinning – Danh Vo’s current exhibition in the Palacio de Cristal in Madrid is a good example – but Calder got there first and is, in many ways, best.

The art that developed between the two world wars was a result of conversations, random meetings and the recognition of affinities. Calder’s meetings with other artists, composers and writers occasioned mutual recognition – and mutual influence. Looking at the painted sheet metal, wood and metal relief panels he made in 1936-37, I wonder how much they might have gone on to influence Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, and even Matisse’s late cut-outs, just as his stark Black Widow of 1948 – the final work in the show, alone in a small room – went on to influence Brazilian neo-concretism, and Helio Oiticica and Lygia Clark. Calder’s sculpture makes its own conversation. With us and without us, it is a performance just the same.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion