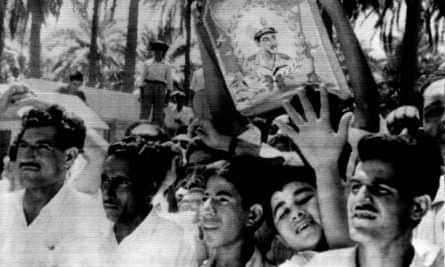

Bagdad, July 25

Bagdad is hot but apparently not excessively bothered as Iraq settles down into its new revolutionary mould.

A ruined office here and there, a plethora of posters, a few erased slogans, an armed guard at the airport, an elated taxi-cab driver - these are the only signs you will see as you drive into the city of the Caliphs that the old order has been obliterated and the house of the Hashemites expunged from Bagdad.

Through a placid veneer, though, some of the violence and tragedy of the coup protrudes. A man demonstrates to you with cruel, clutching movements of his hands how Nuri es-Said was dismembered by the mob. The British Ambassador sits calm but anxious in a suite in the Grand Hotel. A troop of Iraqi soldiers guard the scarred British Embassy, that old symbol of British hegemony.

You ask the whereabouts of a well-known official and the Second Lieutenant gives you a sad, wry smile as he replies: “That gentleman has now retired.” It is a new world in Bagdad to-day. The dear old London buses still lurch down Rashid Street and the British still drink their gin happily enough in its bars; but behind the familiar façade of the city, that mercurial mixture of the sleazy and the brilliant, all is changed and all is blurred.

We do not yet know for certain what kind of a world the revolutionary leaders envisage for their people; whether they want Iraq to maintain her condition of prosperous independence or whether they want to contribute her vast resources to a United Arab State led by Egypt; whether they want to maintain the old special links with the West; whether they are “positive neutralists” like Nasser; or whether they incline towards the Soviet block.

To my mind the odds are heavily in favour of an association between Iraq and Colonel Nasser’s United Arab Republic, with all that such a link would imply; but we don’t really know.

The New Government, under Brigadier Abdul Karim Kassem, has done so many things in so short a time, has upset so many rigidities, and has instituted so many innovations that it is difficult to descry for certain the shape of its policies. It has for example, expressed its regrets to Britain for the assault on the Embassy and has stuck outside the ruined consulate a reproving message to the mob “You should not have done this: these are your friends.” The Embassy will probably be functioning again in its own building in a few days.

Photograph: Ullstein Bild/ullstein bild via Getty Images

Relations with West

It has expressed its admiration for Nasser, but it has reportedly made clear that it intends to preserve the national independence of Iraq. It has dissolved the Arab Union with Jordan, but maintains that the revolution was purely an internal convulsion that will not affect the welcome to journalists from the West. Its relationship with the Western Powers is obviously a peculiar and precarious one, not only because the Western Governments do not recognise it but also because of the Anglo-American landings to the west, which some Iraqis still view as a precursor of a counter-revolutionary assault on Bagdad; yet the Iraq Petroleum Company still seems to be functioning normally and there has been no interruption of the flow of oil to Europe.

Certainly the new Government seems to be in firm control of the whole country and reports current in Jordan of dissident armies bearing down on Bagdad are nonsense. Nearly all the members of the previous Government are under arrest, together with many miscellaneous appendages of the ancient regime. Sixty-eight men are listed as persons who are accused of embezzling people’s property. Corruption seems to be the charge most often levelled against the old order. As the newspaper AI Bilad said this morning: “The small ruling clique simply executed the will of the imperialists to embezzle our wealth.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion