Parts of the brain once thought to be primarily devoted to processing vision can be recruited by blind children as young as five to process speech, a study has found.

The work could have implications for neurologists’ understanding of “plasticity”, or how the brain adapts to experience.

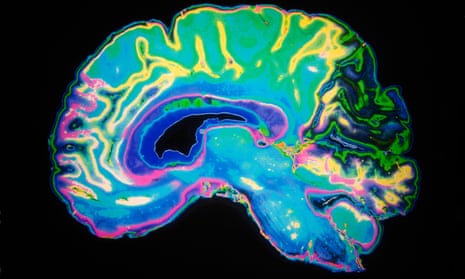

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore used functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI, scanners to study brain activity in congenitally blind and sighted children as stories were read to them and music played.

The children – all of whom were English-speaking – were asked to play a “Does this come next?” game as scientists played audio recordings of stories and instrumental music. They heard either a 20-second clip of music, a story in an unfamiliar language or a story in English. The children were then asked to say whether a follow-up three-second clip was a correct continuation of the story or music they had heard.

The resulting images showed that lobes of the brain once thought to be primarily devoted to processing vision were being used by blind children to process language, findings that highlight both the brain’s adaptability in childhood and the profound impact of experience.

“What I think is exciting about this research with kids – and we’ve done similar things with adults – is the function that you find in the visual cortex is so different [from language],” said Marina Bedny, a researcher on the study and professor in Johns Hopkins’ department of psychology and brain sciences.

“It’s language, which is this abstract function that is uniquely human – unlike vision, which is shared with [most] mammals,” said Bedny. “It shows just how extremely flexible the brain is.”

The study, Visual Cortex Responds to Spoken Language in Blind Children, appears in the Journal of Neuroscience this week. The work was done in partnership with researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

In total, 59 children between four and 17 years old were read stories while an fMRI scanned brain activity. Nineteen congenitally blind children were included, as were 20 sighted children wearing blindfolds, and 20 sighted children without blindfolds.

Unlike the brains of sighted children or children wearing blindfolds, blind children as young as five showed signs of using the visual lobe of their brain while listening to English stories. Researchers referred to this phenomenon as cortex “colonisation”, noting that the visual and language lobes of the brain are adjacent.

Similar studies have been undertaken in adults, with strikingly different results. People who lose sight in adulthood, even for decades, don’t recruit the visual cortex as heavily as children who are congenitally blind (born blind). Case studies of blind adults who regain their sight show that adapting to the new sense can be extremely difficult.

Guinevere Eden, a professor at Georgetown University who studies learning and reading acquisition through neuro-imaging, said the study shows how plastic the brain is at a young age, and in regions that many neurologists still consider static.

“We [neurologists] operate in the sort of classical delineations of the brain, and boundaries of the brain, and what this is showing you is that language lives in a very different part in the room of the house,” said Eden, referring to the brain.

“All these populations have different sensory experiences, and because of that they often have different language experiences … We’re just beginning to understand the complexity of these.”

The results could have future implications for treatment, including considerations about the impact on the brains of congenitally blind individuals of the ability to see. Researchers who conducted the study to be published this week noted the need to repeat the study with another group of blind children, and that the behaviour of the brain in blind children between birth and four is still unknown.

Just a few decades ago neurologists believed the brain’s boundaries were far less porous.

“If you scan 99% of the human population, the neurobiology of people is the same,” said Bedny. At one time, that prompted researchers to conclude that lobes are “built-in”, and homogeneously process certain experiences, such as sight or smell.

However, as Bedny points out, the basic tenets of human experience – sight, smell, hearing, touch and taste – remain consistent across most people. The radically different experience of blind children provides a window into the profound impact those foundational experiences have on the brain, adding another dimension to the question of nature versus nurture.

“There are all these experiences we all share that we don’t think about, like seeing, like hearing, like talking to humans,” said Bedny. “The brain is particularly responsive to experience during this early phase of development – that doesn’t mean it’s not capable of changing in adulthood.”

The research also represents one of the first studies of the brains of congenitally blind children, an extremely small population. The American Printing House for the Blind estimates that 60,000 children (up to age 21) in the US are “legally blind”, a term than covers anyone with sight poorer than 20/200 with the best possible correction. Those children represent about 0.01% of a percent of the US population. An even smaller percentage of children are congenitally blind, or blind from birth, as are those in the study.

Bedny believes such research, which her team hopes to repeat with another group of congenitally blind children, can inform future treatments for the blind. It adds to a body of research looking at how the brain can develop skills to adapt to blindness, such as improved hearing and memory.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion