Madness terrified Vincent van Gogh, yet he also wondered if it was inseparable from artistic genius. In letters to his brother Theo that prove him one of the great writers as well as artists of the 19th century, he broods more than once on an 1872 painting by Emile Wauters called The Madness of Hugo van der Goes, which shows the 15th-century Flemish painter – looking a bit like Stanley Kubrick on an intense day – as a victim of mental illness.

For Van Gogh this painting captured the dark romantic association of genius and insanity. For the modern age, it is Vincent himself who embodies that fatal creative malady. Yet, a new exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam questions what it sees as a romantic myth about the Dutch artist, who lethally shot himself in a cornfield at Auvers-sur-Oise in 1890.

Using a combination of art, written documents and a severely rusted revolver that was found by a farmer in 1960 in that same cornfield, On the Verge of Insanity argues that far from inspiring his art, Van Gogh’s illness was an impediment to his talent. It stopped him working for long periods, and he heroically defied its totally uncreative effects to create some of the most powerful art in history.

When his art, which went almost entirely unsold in his lifetime, started to attract acclaim after his death, this painter of dazzling yellows and hallucinatory blues became seen as cursed by some desperate, mysterious inner pain. The radical French dramatist Antonin Artaud, who spent the later years of his own life in asylums, called Van Gogh a man “suicided by society” and in the 1956 film Lust for Life, he is portrayed by Kirk Douglas as a character tragically unable to control the torrents of emotion and energy that make him a great artist.

This image of Van Gogh as a “mad genius” arguably originates in his own art. In his Self-Portrait with a Bandaged Ear (1889), he dwells on the wound he gave himself when he sliced at his ear with a razor blade in Arles in December 1888 and presented the resulting chunk of severed flesh to a local prostitute. He shows us his maimed face, but it gazes at us with the blue eyes of a visionary. This is not an objective record of a misfortune but, in its hypnotic intensity, a portrait of the artist both martyred and liberated by madness.

The Van Gogh Museum show reveals important new evidence about the loss of Van Gogh’s ear. A recently discovered letter from Dr Felix Rey, who treated his wound, explains the full horror beneath the bandage in his 1889 Self-Portrait. It confirms Van Gogh did not just slice off his earlobe, as has been widely assumed, but his entire left ear. This makes it clearer than ever what an extreme act of self harm it actually was – and how it forewarned of his suicide.

It also disproves the theory advanced by maverick art historians in 2009 that it was Van Gogh’s friend Paul Gauguin who sliced off his earlobe with a sword. You might take off a lobe in a sword fight but the radical amputation that Dr Rey describes is more likely to be a sustained effort with a razor by a man compelled to serious violence on himself.

Similarly, the bizarre claim by American biographers Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith that Van Gogh did not kill himself but was shot by someone else, is challenged by the rare display of the gun he probably used.

This small calibre, 7mm pocket revolver was found where Van Gogh shot himself in the chest and its extreme corrosion suggests it has been in the ground since the 19th century. The pocket gun of a type called Lefaucheux à broche helps explain why the bullet glanced off a rib into Van Gogh’s abdomen and why he took 30 hours to die from a point blank wound.

Other evidence in the exhibition, including his last works of art that reveal his dark psychological state, backs up the museum’s belief that Van Gogh died by suicide, after a long illness that tormented him, and led the people of Arles to mob him and demand his incarceration in an asylum.

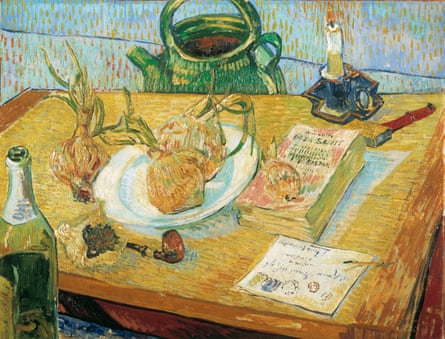

There can be no conclusive diagnosis but Van Gogh suffered from bouts of depression and mental paralysis that periodically crippled him. When he was ill he could not work. Painting, far from a release of his inner demons, was a controlled and steady labour through which he tried to stay sane. He always told his friends to smoke a pipe because that too, he claimed, was a bulwark against madness.

In his painting Van Gogh’s Chair, this simple, steady rustic seat serves as a symbolic portrait. This is how he wanted to see himself – humble and practical, a reliable friend. On the straw seat, he has left the pipe and tobacco he hoped might remedy his inner darkness. He has gone out into the fields.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion