As the protests in Ferguson, Missouri over police fatally shooting 19-year-old Mike Brown have raged through the past several nights, more than a few people have noticed how relatively quiet Facebook news feeds have been on the matter. While #Ferguson is a trending hashtag, Zeynep Tufekci pointed out at Medium that news about the violence was, as best, slow to percolate through her own feed, despite people posting liberally about it.

While I've been seeing the same political trending tags, my feed is mundane as usual: a couple is expecting a baby. A recreational softball team won a league championship. A few broader feel-good posts about actor Chris Pratt’s ice-bucket challenge to raise awareness and money for ALS, another friend’s ice-bucket challenge, another friend’s ice-bucket challenge… in fact, way more about ice bucket challenges than Ferguson or any other news-making event. In my news feed organized by top stories over the last day, I get one post about Ferguson. If I set it to organize by "most recent," there are five posts in the last five hours.

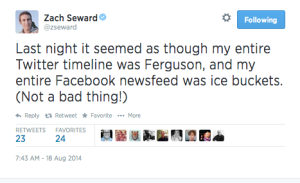

Zach Seward of Quartz noted, also anecdotally, that Facebook seems more likely to show videos of of people dumping cold water on their heads in high summer than police officers shooting tear gas at protesters and members of the media. And rightfully so in Facebook’s warped version of reality: people on Facebook may not be so interested in seeing the latter. At least, not if Facebook can’t show them the right angle. But Facebook’s algorithmic approach and the involvement of content sources is starting to come together such that it may soon be able to do exactly that.

Facebook’s controversial news feed manipulation study revealed, on a very small scale, that showing users more positive content encourages them to create positive content, resulting in a happier, reassuring Facebook experience. Showing them negative content leads to them creating more negative content, resulting in a negative feedback loop.

A second, earlier study from independent researchers in January looked at how political content and debate affects users’ perception of Facebook, their friends, and their use of Facebook. The study found that, because Facebook friend networks are often composed of “weak ties” where the threshold for friending someone is low, users were often negatively surprised to see their acquaintances express political opinions different from their own. This felt alienating and, overall, made everyone less likely to speak up on political matters (and therefore, create content for Facebook).

It’s also well-understood outside of Facebook that people enjoy, and even actively seek, consuming information they agree with. Controversial topics are, right now, poor at providing that experience on Facebook.

One of the things Facebook thrives on is users posting and discussing viral content from other third-party sites, especially from sources like BuzzFeed, Elite Daily, Upworthy, and their ilk. There is a reason that the content users see tends to be agreeable to a general audience: sites like those above are constantly honing their ability to surface stuff with universal appeal. Content that causes dissension and tension can provide short-term rewards to Facebook in the form of heated debates, but content that creates accord and harmony is what keeps people coming back.

Divisive content can be intensely sticky too if shown to the right audience (witness Fox News). But in order for it to stick for Facebook, it has to be shown to the right audience without creating a closed and incestuous circle that prevents viewers or readers from seeing less and less stuff overall.

Recently, BuzzFeed announced an initiative to start posting content directly to sites like Facebook instead of hosting it themselves. Once there, it can be dealt with by Facebook’s algorithm exclusively, potentially serving each article or video directly to its particular audience, however niche or polarized. What shakes out of the BuzzFeed-Distributed approach and a future version of Facebook’s algorithm is the eventual next-level ability to serve viral content, in that it may soon be able to do so using material that suits each user’s particular biases. The tentative approach to Ferguson news shows it’s not there yet, but the pieces are starting to fall into place.

Right now, a lack of information about Ferguson on Facebook, if it's not just a subjective observation, would reflect the wisdom that makes Facebook's news feeds a good experience: keep it happy, keep it nonpartisan. History shows that political events on Facebook can play well, so long as the majority of population is going to fall on the same side: the story of the Boston Marathon bombers played big on Facebook because it was unifying, but arguments about their race and religion, not so much.

If Facebook can take partisan content and use its news feed algorithm to share it with only users who will be reassured by it, it will achieve the significant goal of being all things to all people, the proverbial elephant to society’s various types of blind men. Facebook will know exactly who wants Rush Limbaugh and who wants Rachel Maddow, and what to feed each type of person so that they feel reassured and unchallenged, each existing in their own secure information bubbles. This has potential to relieve some of the universal-appeal pressure on content sources and increase Facebook user engagement. It won’t do much for advancing the level discourse, but that’s never much been what Facebook and viral content was for anyway.

reader comments

88