US president Donald Trump has wrought mayhem on America’s universities without so much as lifting a finger.

College campuses, most of which in the country are predominantly liberal, have become hotbeds of unrest in the mere months since Trump’s election. The University of California’s Berkeley campus, in the face of Trump-supporting speakers coming to campus, rioted. Middlebury saw a physical assault. Wellesley invited former presidential candidate and alum Hillary Clinton to rekindle young graduates’ faith in politics, while a professor at Butler drew up an anti-Trump course, and student groups across the country continued the tireless protests they’ve been leading ever since Trump’s inauguration day.

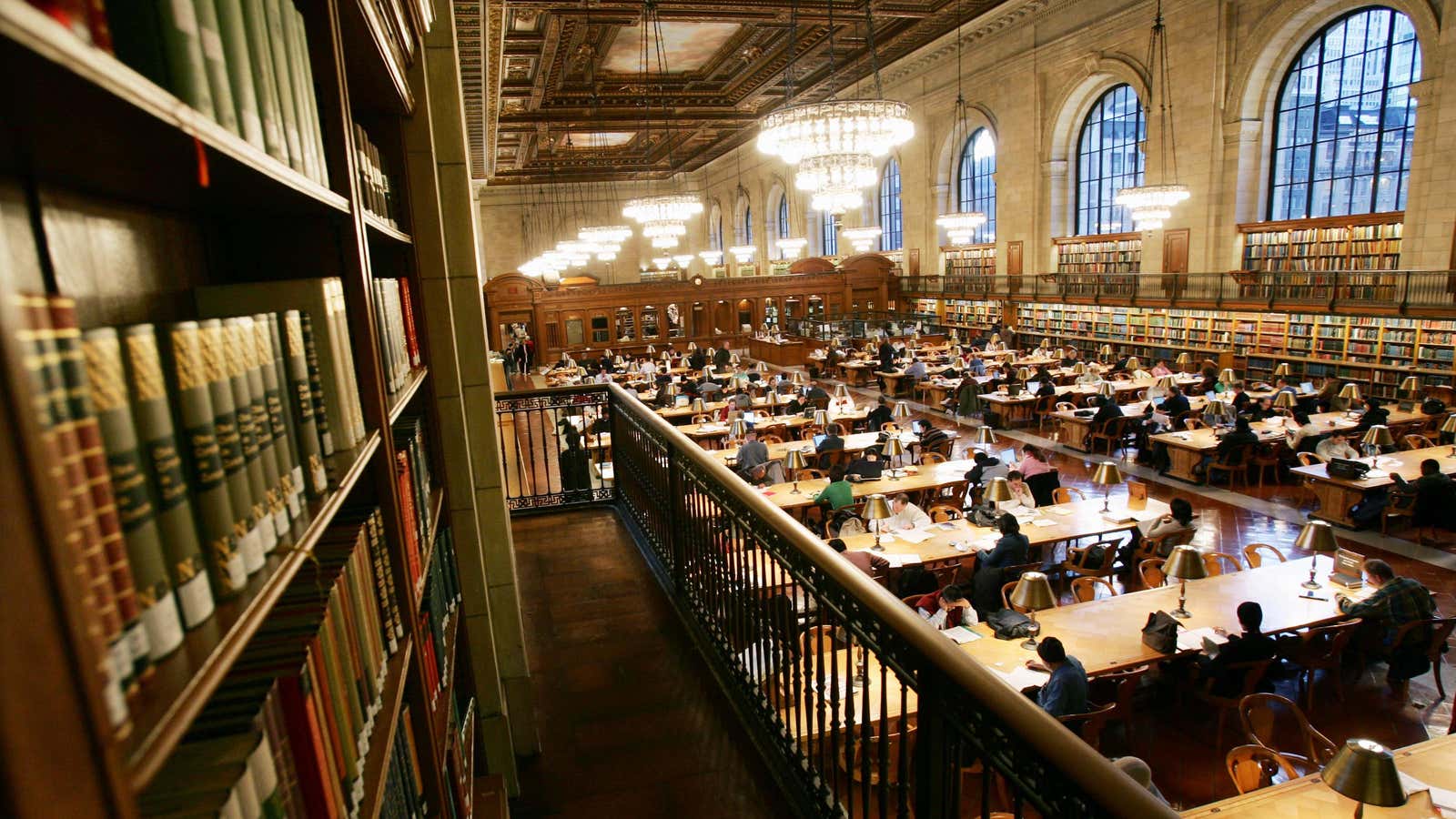

Yet as students march, professors rant, and administrators struggle with the costly cleanup of all the uproar, one body on campus is reaping unexpected rewards from Trump’s chaotic presidency: the fusty old history department.

Stagnant and predictable, the history major had been slowly dying. American college students were turning to fast-paced and dynamic fields like engineering or economics—and ones with a guaranteed salary payoff at the end. In March 2016, the National Center for Education Statistics found that the number of bachelor’s degrees awarded in history was in dramatic decline, falling as much as 9.1% from a year earlier in 2014. The explosive growth of lucrative, forward-leaping Silicon Valley in the last decade seems to have rendered the history major, a curriculum focused on immutable events of decades ago, all the less relevant.

Then came Trump—whose November election brought upon frantic Google searches such as “How did this happen?“

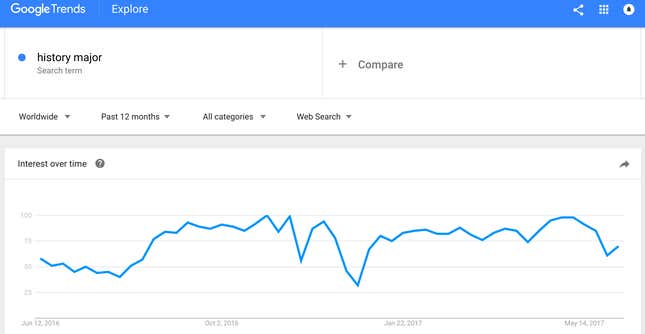

Trump’s win has broken through an apathy barrier of sorts. People who’d become disengaged with politics suddenly started paying attention again. It has spilled over into education: search data reveals a surge of interest in studying history in the latter half of 2016 (with a peak and crash-dip in late December, likely due to that being the deadline for US college applications).

The UK’s historic Brexit decision and the return of nationalism around the world has also helped. At Yale, history was recently revealed as the top declared major for the class of 2019, reclaiming a spot it hasn’t occupied in two decades.

History professors, enthused by the greater student interest in current events, are taking advantage of their sudden revival in relevance, pitching the major to new students as the most practical one of the modern age. It’s not untrue: for those striving to secure the future for generations to come, history may be of much more use than biology or computer science. As Yale history department director Alan Mikhail explains it to the American Historical Association:

Deep sensitivity to the complexities and nuances of society, politics, law, and culture; a willingness to embrace the messiness of the past and hence also the present; a long-term perspective; critical reading habitats; an inherent skepticism of easy answers—all of this and more is the work of historians and is crucial to where we are as a global society right now and will be for the foreseeable future.

Adding to the subject’s comeback is the fact that Trump himself has a less-than-tight grasp on history—politely described by the New York Times at one point as “willful lack of interest”—and is excruciatingly open about it. Nearly in the same breath, Trump has implied the 19th-century abolitionist Frederick Douglass is still alive, “revealed” to the world that Abraham Lincoln was a Republican, and wondered out loud why the American Civil War took place and could “not have been worked out?”

Now facing Trump, Americans are walking back their mockery, and walking backwards in general trying to figure out how the present moment came to be—perhaps taking stock from Winston Churchill, who once said, “The farther backward you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see.”

Not that it always works. George W. Bush, the last Republican president, took the US into two complicated, inextricable wars in the Middle East. He also studied history in college.