Earlier this week, just before bed, an old high school debate teammate, a white man that I once loved affectionately as a younger brother, posted on my Facebook wall, “Do you have sympathy on police officers who are killed on duty?” Though we have been Facebook friends for a number of years, it has also been literal years since our last significant interaction via the site. This was a curious question that seemed forthrightly accusatory in its tone.

Driven, I suspect, by the killing of Texas Deputy Darren Goforth last Friday, my old friend’s question says much to me about the quotidian ways that otherwise well-meaning white people misunderstand racial discourse in this country. Like many Americans, I watched horrified last week as news unfolded of Vester Lee Flanagan’s cold-blooded execution of a newscaster and a cameraman in Virginia. Then, just two short days later, the news that Shannon J. Miles, a Black man with a previously documented history of mental illness, had executed Deputy Goforth made my heart stop.

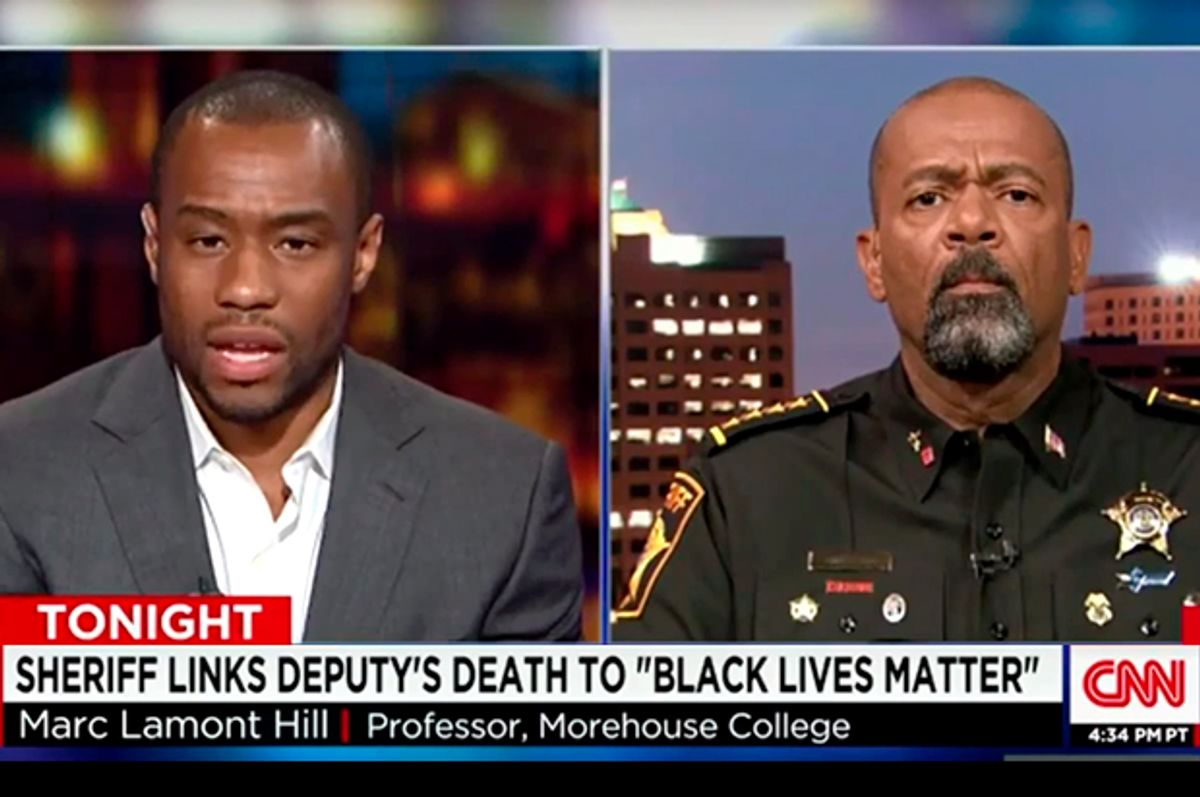

These killings of white people are tragic and inexcusable. That should be said without equivocation. But after I affirmed this same fact to my old friend, I asked him, "What would make you think I think otherwise?” That same night on CNN, I watched Dr. Marc Lamont Hill debate the Milwaukee Sheriff David Clarke, also an African American man. The chief was there to affirm remarks made by Harris County Sheriff Ron Hickman about how “anti-cop” rhetoric from the Black Lives Matter Movement had led to the killing of Deputy Goforth. Sheriff Clarke pointed to the killing of Officers Liu and Ramos in New York last year and the killing of Deputy Goforth, proclaiming it a “pattern.”

How is it that two mentally ill Black men targeting police officers constitutes a pattern, but the killing of Walter Scott, the killing of Samuel Dubose, and the killing of Jonathan Ferrell, all by police while they were clearly unarmed and committing no crimes, add up to a collection of unrelated, isolated incidents? How is it that the random acts of two mentally unstable Black men who had no formal or informal relationship with the Black Lives Matter movement constitute a trend, but the two dozen police killings of unarmed Black citizens again remain a collection of unfortunate but isolated incidents?

In the case of both Samuel Dubose and Walter Scott, we have police officers on tape killing Black men in cold blood, and then we have evidence of those officers and their colleagues blatantly lying about what occurred. This is also true of Christian Taylor in Texas. This is also true in the recent case of two police officers who were fired after video evidence proved they concocted an entire story about anti-cop rhetoric to get out of doing their jobs. If two points make a line, then how many incidents of police caught lying in cases that involve the lethal use of force do we need in order to acknowledge that there’s a pattern?

Let me be clearer. By “we” I don’t mean me. I mean the “We” that was originally included in “we the people.” How many incidents will constitute a pattern for them?

To be clear, the Black Lives Matter Movement is not an anti-cop movement. It is a movement that vigorously and voraciously opposes the overpolicing of Black communities and the state-sanctioned killing of unarmed Black people (and, yes, all people) by the police. It is a movement that insists on holding police accountable for their violence and that will hold police to a higher standard precisely because the state gives police the right to use lethal force. With more power comes more responsibility.

But here’s the thing: White people know this. Conservative Black people who insist on speaking about the rule of law and the issue of Black-on-Black crime know this. This is basic. They know that these young people don’t want to kill cops. They want the cops to stop killing them. That was as true in 1988 when NWA released their hit song, “Fuck Tha Police,” and it remains true today, as protestors blast rapper Boosie’s similarly titled song at protests. Yet, the release of "Straight Outta Compton" this summer has led to increased police presence in movie theaters, even as we have watched the trial of white male Aurora movie shooter James Holmes.

How deeply emotional must one be to hear a group sing a song that is a critique of the police terrorizing communities and hear the song to be saying that these same communities want to terrorize police? How deeply emotional must one be to deliberately disregard the unspoken “too” at the end of every proclamation that “Black lives matter”? We are all entitled to our feelings, no matter how fucked up and misguided they are. But white people’s feelings become facts in a system of white supremacy and these “facts” are used to guide social policy.

Recently, I have come to understand more about the term “gaslighting.” I had heard the term used for years, but never knew what it meant. This particular post explains gaslighting as an attempt to override another’s experience. One key marker of gaslighting is the moment when you name a problem or offense to another person, and somehow they end up the victim. Frequently in these encounters, this person may have said or done something patently offensive, but when you point this out, they accuse you of having lost it, having misrepresented the facts. After repeated interactions of this sort, you start to mistrust your own mind, your own memory, your impressions and interpretations of facts and events. You feel like you must be a horrible person who is causing injury. Yet the emotional bruises you bare tell a different story.

When I read this account of gaslighting, I was reminded of a particularly terrible and emotionally abusive relationship in my early 20s. Over the course of many years, my off-again, on-again boyfriend attempted to erode my self esteem by devaluing the kind of college and grad school I chose, the work I chose to study, and my feminist politics. In one conversation he said to me, “You’re smart. But I’m intelligent. You read a lot of books and you can repeat what’s in them. But I’m more of a natural thinker.” When I became offended, he said, “How is that offensive? It’s true. And it’s a compliment. I said you were smart.”

He was gaslighting me, and over many years of these kinds of conversations, I would often walk away feeling hurt, enraged, and deeply confused and disoriented. Frequently, at the end of conversations, I ended up feeling wrong, apologizing for accusing him of being mean, and trying to make peace, while wondering to myself, “What the hell happened?”

This is not unlike how racial conversations happen in our country. Black communities are experiencing an epidemic of severe police brutality. Even when encounters with law enforcement don’t end in death, they are often shot through with disrespect from officers drunk with power. When we point this out, and when we point to case after case and story after story of inappropriate treatment, we are told that we are merely imagining it. Things aren’t that bad. The cops are the good guys. And see, they get killed, too!

That was the underlying sentiment of my old friend’s post on my page. “The cops get killed, too. And you and your friends and your anti-cop rhetoric are the cause of it.” Such accusations, whether stated or implied, are designed to put Black people on the defensive. We are then supposed to prove that we are both human and humane, non-violent, empathetic, and non-dangerous. We are supposed to prove to white people that we are good people, that we are not a threat, that we mean them no harm. Never mind the harm that many of them have caused us. More than all that, we are not “reverse racists.”

This is gaslighting at its very finest. And it is frequently punctuated with bouts of Black rage. Sometimes that Black rage turns into protest and into the lighting of actual fires. But the stench of burning buildings and the fragrance of rotting Black corpses, whether left to die on a street for 4.5 hours or found hanged in jail cell, are merely the ocular signs of a pre-existing and ongoing cultural conflagration. These fires have been lit for decades by white people, the kindling composed of trees that bare strange fruit, and old, useless, scraps of paper that legally circumscribed the bounds of our semi-precious black lives.

Gaslighting sets your flesh on fire, even though you can’t see the flame. Like a fire shut up in our bones, we feel the burn. We smell smoke. We taste salty tears mingled with blood. We hear the cries of burning flesh. The more that I look at the affective dimensions of Black rage, I see and hear in its notes, exasperation and the deep frustration that comes with being deliberately misheard and misunderstood.

This is what it feels like to talk about race in the dishonest contexts in which we do. This is why many Black people opt out. This is why others scream. This is why some do “inexcusable” forms of violence. I realized that the elders of my youth had their own way of talking about gaslighting. It is a Southern African American proverb worth remembering: “Don’t throw a rock, then hide your hand.”

Shares