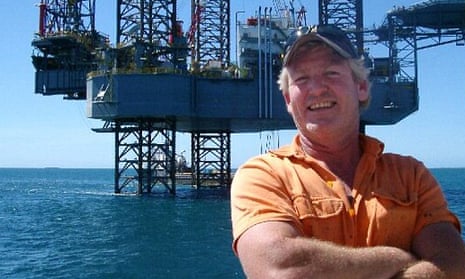

A British citizen who has spent 50 of his 51 years in Australia, who served in the Australian army reserve, and whose partner, siblings and elderly parents are in Australia, is being held on Christmas Island facing deportation for lighting a scrub fire.

Ian Wightman is one of nearly 400 people caught up in changes to Australia’s Migration Act that automatically cancel the visa of a person deemed to have a “substantial criminal record”. That is now defined as a crime carrying a prison sentence of 12 months, even if the time served is much lower.

Wightman was born in London and came to Australia as a one-year-old. He has lived his entire life in Australia. He served two-and-a-half years as a volunteer in the Australian army reserve and has only once visited Britain, more than a decade ago.

His family say he has always considered himself an Australian, even without the formality of citizenship.

Wightman was convicted last year for a fire he lit in 2011. The blaze burned less than an acre of scrubland and did not destroy any property or threaten life.

Wightman served 15 months in jail, his first serious criminal conviction. He had previous driving convictions and low-level drug offences but none that attracted more than a fine.

The court heard Wightman had lit the fire as he battled serious mental health problems brought about by drug abuse.

When Wightman was released from jail in September, Western Australia’s prisoners review board noted he had completed all rehabilitation programs and had demonstrated “a motivation to change his offending behaviour”.

“A limited criminal history indicates an ability to lead a pro-social life,” it said.

But Wightman was apprehended immediately on leaving prison and detained at Yongah Hill detention centre, 90km east of Perth, for eight weeks before he was suddenly flown to Australia’s offshore detention centre on Christmas Island in the middle of the night.

Wightman’s brother Gary told Guardian Australia it was “morally wrong” that his brother was being held in immigration detention indefinitely.

“It’s just wrong on any moral level that people are in there in those conditions. Ian was convicted of a crime, he was sentenced and punished. He served his time and he was rehabilitated. He was released a free man but then they arrested him at the gates.”

He said Ian was finding immigration detention much harsher than prison. He has told family he was “keeping his head down” and did not participate in the riots that razed significant sections of the detention centre this week.

“But it’s just wrong. With prison, you’ve got your start date, you’ve got your end date,” you know how much time you have to serve,” Gary Wightman said. “But this, it’s just the uncertainty, they’ve got no idea when he might be released. It’s unbelievable. This detention is far, far worse than prison.”

Gary Wightman said his brother had told him there were dozens of other detainees – known as 501s after the section of the Migration Act that applies to their cases – with similar lifelong links to Australia in detention, facing deportation to countries they hardly knew.

“Some of the other guys’ stories, they are just tragic. These people shouldn’t be there. This is just wrong,” he said.

Ian Wightman’s partner of more than two decades, Diane Clifton, said Ian’s family had been deeply affected by his detention. His elderly parents had made the round trip from Perth to visit him at Yongah Hill weekly, but now he was on Christmas Island, they could not see him.

“Ian has lived all his life in Australia,” Clifton said. “He pledged his allegiance to this country when he volunteered for the army, I think this is totally unfair.

“There is a chance he could end up in detention longer than he was in jail. According to Australian law, he has served his time. I just can’t see how this is fair.”

Clifton said she had decided that if Wightman was deported, she would go with him.

“I’ll be leaving my job, my family and the life we have here to go to a country I don’t know. I’ll have no family, no support, no accommodation, no employment. That is what these laws are doing, they are breaking up families.”

Guardian Australia has put questions to the immigration department over Wightman’s detention.

But the immigration minister, Peter Dutton, has firmly defended the government’s visa cancellation policies. He told the ABC people were not sentenced to prison terms of 12 months or more for minor offences.

“Nobody’s jailed for 12 months for shoplifting and it defies common sense. So I think people should frankly stick to the facts and I think we’d have a better debate.

“These people [on Christmas Island] are serious criminals and people who have been involved in attempted murder, in manslaughter, convictions for rape, convictions for grievous bodily harm and serious assaults otherwise.”

He said some detainees on Christmas Island had been assessed as an “extreme threat”.

Dutton said visa cancellation for non-citizens convicted of a crime was unremarkable internationally and had been part of Australian migration law since the second world war.

“If somebody is here on a visa ... if they’ve committed a crime they have their visa cancelled. And they face the criminal penalty and administratively their visa is cancelled. In this case they’re taken into custody and they await deportation.”

The number of people detained under section 501 rose more than 600% in a year, from 76 in 2013-14 to 580 in 2014-15.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion