Does Siri make us lazy? Does Facebook make us lonely? Does Twitter make us stupid? Will Google Glass make twitching, distracted Glassholes of us all? If you've read a magazine, listened to a radio show, browsed (or clicked on) the non-fiction section of a bookstore (or Amazon) or been a sentient being any time in the last decade or so, you will have come across some talking head fretting over questions like this. Every new software, every new app, brings about a fresh round of exactly the same cycle of opining: wonder at the possibilities of the technology; alarm about what will happen once we become dependent on it; resignation as we succumb to our digital habits.

There's a subgenre of this techno-handwringing that worries particularly about the effect of our gadgets on our writing. In the quaint early 90s, my English teacher railed against spellchecker for making us careless about reading over our homework. A few years later we were complaining about those green squiggles plaguing our Word documents, harping on our "wordiness" and "use of contractions" but never once catching a dangling participle or a malaproprism. Now we're in the age of autocorrect, where our smartphones hijack our well-intentioned messages, making them so consistently inappropriate that there are websites like Damn You, Autocorrect! devoted to exhibiting the worst of the manglings.

It's certainly entertaining to dwell on the ways our newfangled word-delivery programmes can foil our pursuit of precise language. What's easy to overlook, however, is that at the centre of any transmission of text is another idiosyncratic processor on which we're utterly dependent and which just as easily leads us astray: the brain.

Our brains, you could say, are the original autocorrectors. In her book Being Wrong – a meditation on human error of all kinds – Kathryn Schulz explains how we constantly take sensory messages from the world and unconsciously alter them slightly. She points out that, for the most part, these alterations serve us well: take the blind spot, which is the part of the eye where the optic nerve passes through the retina and blocks the reception of visual information. Even though each of us has one, none of us sees blanks in our field of vision, she says, "because our brain automatically corrects the problem".

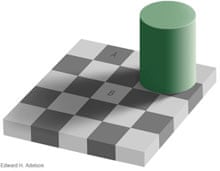

Schulz gives dozens of examples how our perceptual processes are founded on filling in gaps and leaping to conclusions. She shares this amazing illusion:

It might be hard to believe, but the square marked A and the square marked B here are exactly the same shade of grey. We don't "see" it this way, she explains, because "when it comes to determining the colour of objects around us, our visual system can't afford to be too literal". Instead, our understanding of colour is relative, contextual; we automatically adjust for cast shadows, mentally lightening the objects they fall on.

And when it comes to text, we're just as likely to see what's convenient to see. A friend recently shared this trick with me. Read what's written in the triangle below out loud:

Did you notice the typo within these seven words? Most people skip right over it.

Then there is this old internet meme:

I cdn'uolt blveiee taht I cluod aulaclty uesdnatnrd waht I was rdanieg: the phaonmneel pweor of the hmuan mnid. Aoccdrnig to a rseearch taem at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it deosn't mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoatnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer be in the rghit pclae. The rset can be a taotl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit a porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe. Scuh a cdonition is arpppoiatrely cllaed typoglycemia.

No matter that there is no such research team at Cambridge, and that typoglycemia is something of a gimmick and a myth. The point this scrambled paragraph makes – the point that all of these visual games leads me to – is that a normal functioning human is one that sails blithely past mistakes in a text while understanding perfectly what it means.

The next natural step in this line of reasoning is that anyone whose job it is to catch these mistakes – editors, copyeditors, subeditors, proofreaders – has to be an abnormal and malfuctioning human.

This is one part of being an editor that no one much talks about. Sure, you have to know your way around commas and colons. You should have a feel for the nuances of syntax and the rhythm of sentences. You want to be sensitive to a writer's intentions and a reader's attentions. But you also need to be able to look at a page without using your brain. Put another way, you need to be able to look at words in a way that goes against everything your brain would naturally do when it looks at words.

For my own work, I rely mostly on a constant and blanket distrust of my eyes, alongside a series of convoluted psych-outs to keep myself from reading as a normal person would. I'll move a ruler down the page line by line so that I don't skip ahead. I'll read text aloud and backwards; I'll look at pages upside-down. Then I'll give to someone else – or rather to four other people – to read. After that I'll open it up on the screen and run a couple of spellcheck on it for fun. And then I'll read it again.

Because there's no one trick or programme that guarantees that I'll catch all the mistakes, a handful of tricks, a few different brains and a programme or two is the closest we can come to foolproof. In the end, there's no switch we can press on to turn off the wildly interpolative, inaccurate, imaginative text decoder built into our systems, which is of course what sets us apart, for the time being and for better or for worse, from our machines.

Yuka Igarashi is the managing editor of Granta magazine.

Why We Make Mistakes, hosted by Yuka Igarashi, part of Hendrick's Carnival of Knowledge at the Edinburgh fringe, will take place today (Friday 9 August) at 1pm at One Royal Circus, Edinburgh. Tickets here.