Back in 2012, the British Library displayed a rare book that attracted as much media attention as a Gutenberg Bible. It was a mass-produced edition of a text once owned by Nelson Mandela, inked with his pen. Mandela had kept this volume by his bedside for more than 20 years and it had sustained him through his darkest hours on Robben Island. Sometimes he had read aloud from it to his cellmates.

It was not scripture, but its sacred characters – from Hamlet to Prospero – had often been a source of inspiration. Mandela, son of a Xhosa chief, was born and grew up in Transkei, 6,000 miles from Britain. English was never his mother tongue. But, speaking about the Collected Works of William Shakespeare, he once said: “Shakespeare always seems to have something to say to us.”

That heartfelt response is, perhaps, Shakespeare’s most astonishing achievement. Four hundred years on, his unique gift to our culture, language and imagination has been to universalise the experience of living and writing in late 16th-century England and to have become widely recognised, and loved, across the world as the greatest playwright.

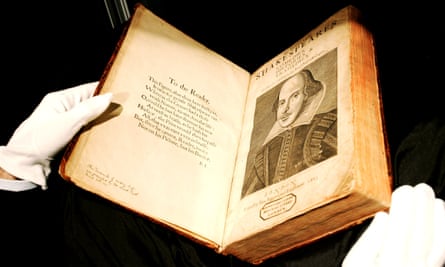

Shakespeare’s double life, as both an English and a universal artist (poet and playwright), begins with the First Folio of 1623. His friend Ben Jonson, addressing “the Reader”, initially says that “gentle Shakespeare” is the “soul of the age”, placing him firmly in a metropolitan context, as “the wonder of our stage”. A few lines later, however, Jonson contradicts himself, declaring that his rival “was not of an age, but for all time”.

This dynamic duality runs throughout Shakespeare’s life and work, making him an androgynous and timeless shape-shifter who is impossible to pin down. He’s “a man of fire-new words” (“equivocal”, “prodigious” and “antipathy”, for instance, get their first citations from him), with a vocabulary of 30,000 words. But he is also the master of the simplest construction, such as Henry’s devastating rebuke to Falstaff (“I know thee not, old man”) or Leontes touching Hermione’s statue in The Winter’s Tale (“O, she’s warm”), three words that any child could understand.

Every generation continues to be in his debt. Shakespeare’s plots, which are brilliantly polyvalent, continue to inspire ceaseless adaptations and spin-offs. His unforgettable phrase-making recurs on the lips of millions who do not realise they are quoting Shakespeare: “a fool’s paradise”; “the game is up”; “dead as a doornail”; “more in sorrow than in anger”; “cruel, only to be kind”; and dozens more. Elsewhere, words and phrases from his plays have become seeded into the titles of countless novels and films from Brave New World (Aldous Huxley) and The Sound and the Fury (William Faulkner) to The Glimpses of the Moon (Edith Wharton) and The Dogs of War (Frederick Forsyth).

As well as giving the English language a kick-start, Shakespeare can also conjure characters apparently out of nowhere, giving “to airy nothing a local habitation and a name”. He has populated our imagination like no other writer: Hamlet, Juliet’s Nurse, Macbeth, Mistress Quickly, Lear, Othello, Shylock, Portia, Prospero and Romeo … the list of classic archetypes stretches out to the crack of doom (Macbeth), a cast of characters perhaps more real to us than any others in our literature.

The plays, often rooted in ancient myth, in which these theatrical legends appear, have become archetypal stories, too. More than Dante for the Italians, Goethe for the Germans, or Pushkin for Russia, Shakespeare remains an icon for English-speaking peoples throughout the world. Such ambitions came naturally. From the first, he was always pitching his work on the biggest stage imaginable. The motto of the Globe, his theatre, was Totus mundus agit histrionem (The whole world is a playhouse).

At the same time, as a glover’s son and a grammar-school boy from Stratford, Shakespeare projects a uniquely English, and rather modest, sensibility. His plays seem to tell us that here is a great writer who is happily steeped in low culture and the English countryside as much as court politics and affairs of state. There is something appealingly English, even offhand, about his titles: As You Like It, Much Ado About Nothing and All’s Well That Ends Well. Even Twelfth Night is subtitled What You Will. The young Shakespeare’s message to his audiences seems to be that there might be other things to do than write plays. As well as the nailbiting intensity of Othello or Macbeth, Shakespeare can embody the laid-back nonchalance of the English amateur.

Typically, Shakespeare seems to have left the stage with scarcely a backward glance. He simply retired to Stratford, collaborated a bit with a few former associates, got drunk with some old friends and died, having bequeathed his “second-best bed” to Anne Hathaway, his wife.

Despite having forever changed English life, language and culture, at home and abroad, Shakespeare remains an enigma. His work is a mirror on which we can reflect themes of love and hate, war and peace, freedom and tyranny, but the man himself is mysterious. After 400 years, such magical invisibility makes him more than ever godlike.

William Shakespeare and the American Dream, by Robert McCrum, is broadcast on BBC Radio 4 at 9am on 19 April and 24 April.

Language

Shakespeare was a writer who always seemed to be able to do what he wanted with the language, marrying Anglo-Saxon, continental and classical traditions in a weave of poetry and storytelling. The dramatist of the First Folio was a literary magpie, “a snapper-up of unconsidered trifles” and a master of artistic synthesis. The Stratford of his youth lurks behind the facades of Verona, Syracuse or Padua, just as the “citizens” of his Vienna, Rome or Athens seem to have stepped straight out of Cheapside or Southwark. When the good vernacular gets braided with Latin coinages, the English language is remade and renewed.

Modern man

“Who’s there?” is the opening line of Shakespeare’s most famous play. Hamlet answers this uniquely modern question by redefining the theatrical expression of identity. It’s a project Shakespeare revels in. “What a piece of work is a man!” exclaims Hamlet, in the voice of the playwright. Shakespeare’s student prince is the first western dramatic protagonist to be conceived as an individual tormented by complex inner conflicts and desires. “To be, or not to be”, Hamlet’s contemplation of suicide, is a pioneering and sensational moment of post-renaissance drama: stunning poetry articulating brilliant psychology. Later, in the celebrated gravedigging scene, “Alas, poor Yorick” juxtaposes high and low culture to articulate the mature Shakespeare’s existential vision of human frailty.

The American dream

Shakespeare is not just an icon of Englishness. He’s also a central feature of the American dream, in which the mirror of his great dramas gets held up to a society permanently in search of itself. When former president Bill Clinton says “our engagement with Shakespeare has been long and sustained: generation after generations of Americans has fallen under his spell,“ he’s acknowledging this most surprising fact – that Shakespeare’s afterlife as the greatest playwright is now as much an American as a British phenomenon, integral to American culture and society. His statue in New York’s Central Park, erected by the brother of John Wilkes Booth after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, symbolises the role of Shakespeare in American life.

Heritage

The actor David Garrick almost single-handedly resurrected Shakespeare’s 18th-century reputation with his Shakespeare Jubilee of 1769, a belated recognition of the playwright’s bicentenary. Stratford now became the hub of the Shakespeare memorial industry (gloves, rings, mugs, knick-knacks). Two future US presidents, Jefferson and Adams, visited “the birthplace” on Henley Street and paid a shilling to see Shakespeare’s grave. “There was nothing preserved of this great genius,” wrote Adams, sadly, “which might inform us what accident turned his mind to letters and drama.” This has never inhibited the American “bardolatry” which, during the 19th century, would morph into bizarre (and ultimately pointless) disputes about the authorship of the plays.

Film

Othello (lust, jealousy, and betrayal), Macbeth (paranoid regicide), Romeo & Juliet (doomed love) and many of Shakespeare’s greatest plays were an instant hit with Elizabethan audiences. Hollywood scriptwriters quickly latched on to Shakespeare’s (often borrowed) plots and icons. Great stars hanker after the great roles: Olivier playing Henry V, Paul Robeson playing Othello, Orson Welles playing Falstaff, and Gielgud playing Prospero. Similarly, Macbeth inspired Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood; Gus van Sant remade Henry IV as My Own Private Idaho; and Ran is a classic Japanese homage to King Lear.

Celebrity

This portrait of Shakespeare, one of several contested images, seems to capture the artist in his prime. Here is the “soul of the age”, the author of The Sonnets, Hamlet, As You Like It and Henry V, taking a break from the playhouse to practise something he rarely enjoyed: promoting his image. The writer described as “not a company keeper” was usually too busy with literary and theatre business to waste time on self-publicity. He understood that it was the work that mattered, not the hoopla that accompanied it. Unlike Ben Jonson, his competitor and contemporary, he seems to have showed virtually no interest in posterity.

Psychology

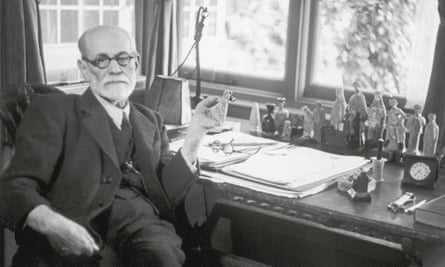

Freud thought Shakespeare “the greatest of poets” and was always ready with apt quotations from the collected works. His recognition of the unconscious took Shakespeare’s fascination with the mind of man to a new level and he scattered the poet’s insights throughout his own psychoanalytic writing. Freud’s stock-in-trade – duplicity, envy, desire, and conscience – is all grist to Shakespeare’s mill, from “there’s no art to find the mind’s construction in the face” to “the stroke of death is as a lover’s pinch, which hurts and is desired”. When Richard III is facing his downfall, he declares: “Conscience is but a word that cowards use, Devis’d at first to keep the strong in awe.”

History

Shakespeare, the Tudor propagandist and author of Richard III, still dominates the narrative of English history. His devastating portrait of the hunchbacked king as a “bottled spider” has had a long afterlife. Not even Shakespeare could have anticipated the discovery of the deposed king’s bones in a Leicester car park though he would have relished the irony. In the play, the king’s disguise of his “naked villainy” is Shakespeare at his most potent, caricaturing Richard’s ambition to “seem a saint, when most I play the devil”. Abroad, the play still resonates as a lethal blend of tragedy and history. In the darkest days of the Watergate scandal it would be resurrected in America as a commentary on Richard Nixon’s abuse of power.

Refugees

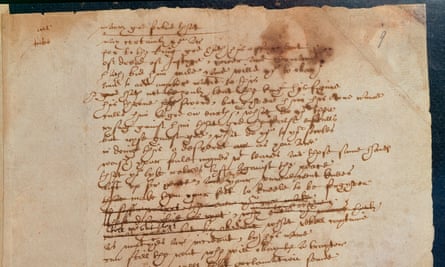

The Holy Grail of Shakespeare scholarship: an autograph manuscript. The text of Sir Thomas More was a collaboration, typical of Shakespeare’s apprenticeship. It is, however, the only surviving manuscript, apart from some legal documents, in which the playwright’s handwriting (“Hand D”) can be clearly detected. This thrilling document also demonstrates the playwright unerringly drawn to a timeless (and modern) theme – the fate of the dispossessed. The speech Shakespeare writes here contains an impassioned plea for sympathy and understanding towards the plight of refugees.

Music

Shakespeare’s genius for dramatic clarity makes his work perfect for opera. Verdi was obsessed with the plays. Three of his finest operas (Macbeth; Otello; Falstaff) are Shakespearean. West Side Story (Romeo & Juliet) is not just Bernstein’s masterpiece. In 1961, the film of the production became a worldwide hit. Other great classical composers who loved Shakespeare include Berlioz (The Tempest), Mendelssohn (Midsummer Night’s Dream), and Tchaikovsky and Prokofiev, both inspired by Romeo & Juliet. More popularly, Shakespeare would have loved Cole Porter’s music for The Taming of the Shrew (Kiss Me Kate) and his celebrated Brush Up Your Shakespeare, a theme song for this quatercentenary.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion