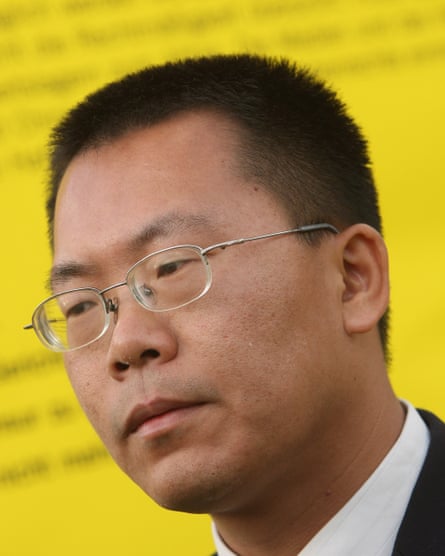

As Chinese activist and scholar Teng Biao sat at home on the east coast of America, more than 13,000km (8,000 miles) away his wife and nine-year-old daughter were preparing to embark on the most dangerous journey of their lives.

“My wife didn’t tell my daughter what was going on,” said Teng, who had himself fled China seven months earlier to escape the most severe period of political repression since the days following the Tiananmen massacre in 1989.

“She said it was going to be a special holiday. She told her they were going on an adventure.”

One year after their dramatic escape through southeast Asia, Teng’s family has been reunited in New Jersey and is part of a fast-growing community of exiled activists and academics who feel there is no longer a place for them in Xi Jinping’s increasingly repressive China.

Jerry Cohen, a veteran China expert who has offered help to many of the new arrivals, said he had seen a significant spike in the number of Chinese scholars such as Teng seeking refuge in the US last year.

Until about 12 months ago China’s top universities “remained islands of relative freedom”, said Cohen, who has studied the Asian country for nearly six decades.

“[Now] I think there is much more attention to what you teach, what materials you use, what you say in class, what you can write and publish, whom you can contact, where you get your support. I think a lot of people are just getting disillusioned and feel at least for a few years they’d better ride out the Xi Jinping storm [overseas].”

Cohen likened the influx of intellectuals – mostly political scientists or international relations and law experts who have sought permanent or temporary positions at US universities – to previous waves of refugee scholars who fled the Nazis during the 1930s and 40s, and China following the Tiananmen crackdown.

The most famous was Albert Einstein, who moved to Princeton in October 1932 and campaigned to help other Jewish refugees secure asylum.

“It is not as dramatic as the refugees from Hitler; not as dramatic as the enormous number who turned up [after Tiananmen] and we had to deal with,” Cohen said. “But it is growing and I am seeing them.”

Carl Minzner, an expert in Chinese law and politics at Fordham University in New York, said he had also noticed an increase in Chinese academics “strategically opting to have one foot out of the door” by relocating to the US.

“You are a small ship that is being tossed in the storm and everybody is looking for their safe harbour,” he said.

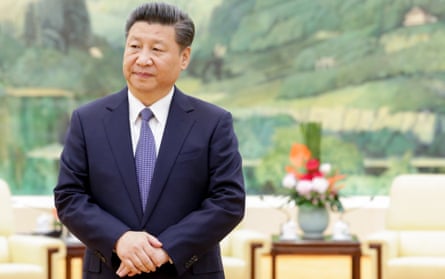

When Xi came to power in November 2012, some observers hoped his 10-year reign might usher in a period of political and economic reform. They pointed to Xi’s father, the reform-minded party elder Xi Zhongxun, as evidence of the liberal tendencies of China’s incoming leader.

Instead Xi’s ascent marked the start of what many observers now call an unprecedented crackdown designed to silence opposition to the Communist party ahead of a painful economic slump.

Activists, journalists, bloggers, feminists, labour campaigners, religious leaders and rights lawyers have been interrogated, harassed or even disappeared and jailed. Liberal academics have also come under increasing pressure.

Despite the fact that Xi’s own daughter studied at Harvard University, a series of Communist party decrees have ordered a purge of hostile western liberal ideas such as democracy and rule-of-law from Chinese campuses.

In a recent interview with the New York Review of Books, the head of one prominent thinktank said the situation had become intolerable. “As a liberal, I no longer feel I have a future in China,” said the academic, who is in the process of moving abroad.

Teng, 42 and a former lecturer at Beijing’s University of Politics and Law, said Xi’s rise to power had been a turning point.

“Things got worse rapidly after Xi came in,” he said, speaking in his office in New York University, where he is now a researcher. “President Xi lowered the threshold for imprisoning people, and adopted a zero tolerance policy on human rights.”

As one of China’s most prominent civil rights lawyers Teng found himself at the eye of the storm. He was one of the founding members of the New Citizens’ Movement – a now defunct civil rights coalition wiped out by security services after Xi came to power – and, even before Xi’s rise, faced repeated spells of house arrest and surveillance.

In September 2014, as Beijing’s crackdown deepened, he decided to abandon China, flying out of Hong Kong with his youngest daughter to take a position at Harvard University through its Scholars At Risk program.

“I felt that the space of civil society had become so limited I had to leave,” said Teng, a graduate of the prestigious Peking University.

Many of the Chinese academics now rolling up on American shores prefer to keep a low profile to avoid attracting unwelcome attention from Chinese secret police.

“A lot of these people are not overt defectors,” said Cohen. “They are just people who are wisely adjusting their behaviour to a future that is ever more uncertain.”

But Teng has refused to go quietly.

Since touching down in the US he has remained as active as ever, posting on Twitter and other social media and keeping in touch digitally with a global network of human rights lawyers, officials, politicians and international campaigners. On Wednesday he will appear at a session of the Conservative party human rights commission in London for the launch of a report about the deteriorating situation under Xi.

Recently Teng has also been hyperactively disseminating material from the Panama Papers in an attempt to try and pierce the Chinese government’s severe censorship of documents revealing that relatives of some of the top leaders had been hiding wealth in secretive offshore companies.

“We’ve tried to spread the information on WeChat and Twitter. They delete the posts, but we then re-post it. Even though the censorship is very strict we can play this cat and mouse game, and then some Chinese people will know about this and the authority of Xi Jinping and the top leaders and their family members will be impacted.”

The life of an exile does not come without a cost.

Teng, originally from Jilin province in northeast China, says he misses his family and friends back home, “but mostly I miss the feeling I had when fighting for freedom and human rights together with my fellow lawyers and defenders. It was both interesting and meaningful. We knew it was risky, we knew we could be put into prison or have other trouble, but all of us thought it was worth trying to do something to push forward with the law and freedom in China.”

He said he also suffers from what he called “survivor’s guilt”: “So many lawyers, many of them my close friends, are in prison and in detention. I am free, so I feel I have a special obligation to speak for them.”

Cohen said he sensed great sorrow among many of the uprooted academics he met.

“They don’t want to leave. They were playing important roles in their universities or their law schools or whatever,” he said. “Of course if they end up getting a professorship at Columbia or Singapore they have to see the virtue of that – they have children to take care of.

“But it is a sad thing for them to be stimulated by repression to have to leave their own country, even if some of them are lucky and land on their feet.”

Cohen predicted that in exile many would simply become “second-class citizens and will never achieve what they could have had they stayed home”.

For now, Teng said his family was happy in New Jersey. His two daughters, now eight and 10, have enrolled in a primary school where he said they were no longer force-fed propaganda about “the Great Chairman Mao Zedong” or Lei Feng, a Mao-era military officer held up by Beijing as an example of devotion to the Communist party.

Despite having to live thousands of miles from home, he tries to keep his children in touch with their Chinese roots. “We tell them that Chinese culture is wonderful but that the current political system is not good.”

In April, amid the intensifying crackdown, Xi said the Communist party “should fully trust intellectuals and create a favourable environment for them to exercise their talent and develop their careers” in China.

Scholars “should not be blamed or punished for expressing their opinions,” Xi said, according to the official Xinhua news agency – but they should also be sure to follow the “right path”.

For now a return to China, where some of Teng’s best friends still languish in jail, is not on the cards. “I want to, but I’m quite sure that Xi Jinping and the Communist party will not allow open society and political reform, and they will not give up their power. Life will remain very difficult for human rights activists,” he said.

Yet even in these dark times, he remains optimistic, vowing to continue fighting from afar so his daughters might one day return home to a changed country.

“I’m quite sure they will come back to a free and democratic China,” Teng said. “I don’t know how long it will take but many dissidents and activists are fighting for a better China. They don’t want the next generation living in fear.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion