“Gathering all this mass in fewer than 690 million years is an enormous challenge for theories of supermassive black hole growth,” Bañados said.

With a mass of approximately 800 million times that of our Sun, the black hole fits into the “supermassive” category, which includes some of the largest objects in the universe.

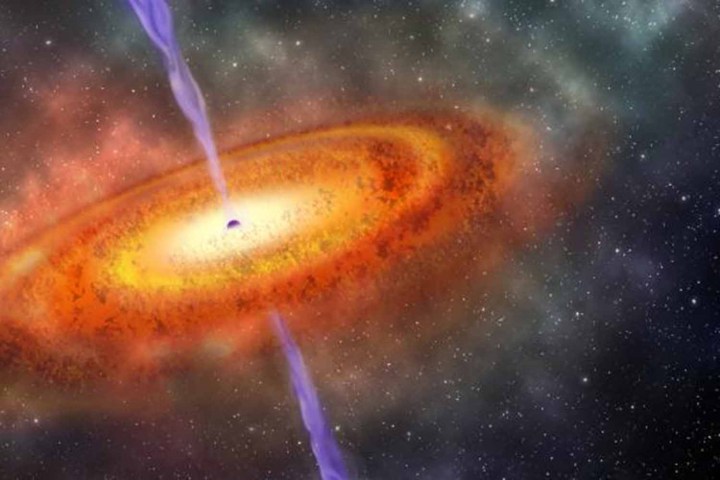

The black hole was found within a quasar, immensely luminous objects with hearts of matter-ejecting black holes.

Black holes that form in the environment of today’s universe (which is about 13.8 billion years old) rarely grow to a few dozen times the mass of the Sun. In the “dark ages,” when the universe was just a few hundred million years old and stars were first forming, astronomers speculate that conditions allowed black holes to reach some 100,000 times the solar mass. It’s these conditions that have enabled the quasar to grow so massive and bright.

The recently discovered quasar is more than thirteen billion light years away, meaning the light seen through the Carnegie telescope represents the blackhole at just a fraction of its current age. It would be like seeing a picture of a middle-aged woman when she was just a toddler.

“This great distance makes such objects extremely faint when viewed from Earth. Early quasars are also very rare on the sky. Only one quasar was known to exist at a redshift greater than seven before now, despite extensive searching,” Xiaohui Fan, an astronomer at the University of Arizona’s Steward Observatory, said.

Bigger black holes abound in the cosmos, but none yet have been discovered so far away from Earth. Only one other quasar has been discovered at a comparable distance, but the recent discovery still out paces it by around 60 million years. The researchers estimate that between 20 and 100 quasars of this size and distance exist in the universe.

A paper detailing the research was published this week in the journal Nature.

Editors' Recommendations

- Astronomers spot two black holes colliding in epic merger

- Research confirms enormous mass of supermassive black hole at center of galaxy

- How James Webb will peer through a dusty cloud to study supermassive black hole

- See a map of 25,000 supermassive black holes in distant galaxies

- Stuff of nightmares: Black holes one hundred billion times the mass of the sun